By Vidhya Nair

VN: Tell us about your background individually and together?

MSM: I’m a 3rd Generation Singaporean of Punjabi descent. I have a younger sister who’s married and settled in Sri Lanka and my mother’s extended family still live in Medan, Sumatra where my mother is from. Dayanand is from a Malayalee-Menon family. As Singaporean Indians, I see that we have a shared history so even the diversity in our cultural nuances is easily accessed. My father was always interested in the arts and culture since he was young. My paternal grandfather was close friends with Dr Chotta Singh [ medical doctor and founder of the Ramakrishna Sangeeta Sabha – the first Indian Orchestra of Singapore] who ran a small clinic in Serangoon Road. Coincidentally, he was also known to the Menon doctors who ran Lily Dispensary & Clinic [ incidentally part of Dayanand’s extended maternal family]. My father used to perform with the Indian Music Party singing Hindi songs at Malay and Indian weddings in the late 1950s. He was also part of the Singapore Indian Film Arts and Dramatic Society and in 1964 was one of the judges for the saree queen contest which took place at the then brand-new National Theatre. [ Located on the slope of Fort Canning Park and River Valley, this was the first and largest theatre built in 1963 and demolished in 1986 to make way for building part of an expressway]

DM: My parents came from Kerala. Mother from Palghat* and father from Thrissur. It was just me and my elder brother. In Singapore, I was born in the Moulmein Rise area and subsequently lived in Whampoa Drive from 1973-74, a few blocks away from Monica but we never knew each other then. The Whampoa Canal divided our area. We lived a simple life, no luxuries and went to neighbourhood schools. My father worked with the Royal British Airforce and my mother was a homemaker. It was a traditional Malayalee home but we brothers spoke in English. In retrospect, our family setup lent itself to us growing up with mastery in the English language although we lost out culturally as compared to our contemporaries. My parents were generally introverts and I only learned more about Amma’s early life post her death in 2015 where I was told that she was a vibrant youngster and extremely talented. Following her father’s lineage, she was often involved in theatre and performed on stage in her younger days. My parents weren’t active in the community and were relatively unknown but we were happy as private people. I was part of my primary school band, had an ear for music but I could never read the score. I think I was artistically inclined and took part in school plays but it was not nurtured or encouraged at home. I later trained to be a teacher then went on and studied in Canada. Upon my return I started with some relief teaching, which is how I met Monica at Towner Primary school. Later, I worked in the Big 4 Audit firms and today, I run my own accounting practice.

* Dayanand’s maternal grandfather – K P Apukuttan Menon lived in Singapore from the early 1920s and worked as a court interpreter during British rule, raising his 5 children here before returning to Palghat, Kerala. He was a performing member of Dr Chotta Singh’s Ramakrishna Sangeeta Sabha orchestra playing the jalatarang in 1940 and was the founding President of Indian Fine Arts Society (later SIFAS) in 1949 serving 2 terms. When K P Bhaskar arrived in Singapore from Ceylon in 1952, it was K P A Menon who met him at the docks and arranged for him to teach dance to students at Kamala Club while he was in transit to go onward to Australia. This connection was made by K P A Menon’s elder brother K P Keshava Menon who was the High Commissioner of India to Ceylon and had met K P Bhaskar and helped him with his Australian visa. K P Bhaskar eventually stayed on in Singapore and formed Bhaskar’s Academy in 1952. K P K Menon lived in Singapore from 1925-1948, practiced as a barrister & was involved in the early formation of the Indian National Army and was also incarcerated by the Japanese in Singapore. He returned as a nationalist war hero to India and continued to be editor of the Malayalam newspaper he founded, Mathurbhumi till his death. His only son, the last King of Palghat M S Varma lived in Singapore to be a centurion, left for Calicut at the age of 102 and died in his niece’s home in Calicut in 2015.]

VN: Monica, how did you come to become Maami’s student?

MSM: My father believed that having an extra activity outside school was essential and my sister and I came to be sent for Sunday dance classes in the recreation centre at Farrer Park with K P Bhaskar in the late 1970s. After two years, my father felt we was not progressing and transferred us to Kamala Club to learn under Madhavi Krishnan. However, she eventually relocated to Australia and we went in search of another teacher. My father had heard of Mrs Neila Sathyalingam sometime in 1978, and had gone to Tanglin CC to meet her. So, on advice from his friend, Mr Ramachandran, who a was a fellow vocal & percussion, my father then enrolled us at Kamala Club, where Neila Maami had moved and this was ideal as it was close to Whampoa Drive where we lived. I began learning from Maami from 1981 and was her student for almost 36 years till 2016 before she took ill. While I took short breaks, during exams and my wedding and childbirth etc, I always went back to her for classes after that.

VN: Share with us the role Mami played in your lives?

MSM: I’ve come up with 3Es that epitomises what Mami did. Exposure, Experience and Experimentation.

Reflecting back, my sustained interest in dance was not about taking examinations but I was drawn instead to some of values Maami and the art form inculcated. Discipline, “me-time” and an outlet for self-expression became a routine and mantra for me. As I grew older, I became drawn to the art form, but more importantly, I found a mentor in Maami. I learned how to drape a saree neatly from Mami – how to pull the pleats, shape the saree, and how it should be pinned, etc. It was more than just a Bharatanatyam lesson – your whole persona was shaped through interactions with Maami. Maami was there all the way for me in all the important aspects of my life even on my wedding day. She made a contribution to my total development as a person. I don’t know if there are any other teachers like Maami.

When Dayan and I were courting, I made it clear that dance was going to be a constant and if he didn’t support it, he would need to find himself another wife! I said this to him as I as I saw several of my contemporaries having to give up dance classes once they became wives and mothers. I didn’t want to give up the ability to continue to learn dance. I became an educator along the way and initially, as part of my CCA, and before we could engage external instructors, I used to help with the dance choreography for our students participating in the Singapore Youth Festival (SYF). Hence, my ability in dance gave me some additional leverage in designing costumes & selecting music pieces.

Maami was a person who was way ahead of her time. She knew how to draw on people’s strengths and she was someone who invested in her people. She was someone who could spot talents – what you had and how to place you. For me, this was a standout characteristic of Maami. It was Maami who helped me to get my first job and it was there I met Dayanand. When I finished my A Levels, I received a call from Mrs Sundram , who was acting Vice-Principal at Towner Primary School and a close friend of Maami, asking me to come in for a relief teaching position.

She was a mover and a collaborator – when Apsaras Arts first began to travel overseas to Australia (for the Arts festival there), the whole company would uproot, travel and be away for 3 weeks. I recall her asking me to cover the juniors’ classes at Cairnhill Community Centre during their absence. It was an honour for me to be entrusted to teach on her behalf. It was also an unexpected surprise to receive a small cash gift from Maami for the time spent teaching but this was Maami, she put in a lot of effort in the little things, like knowing how and when to appreciate.

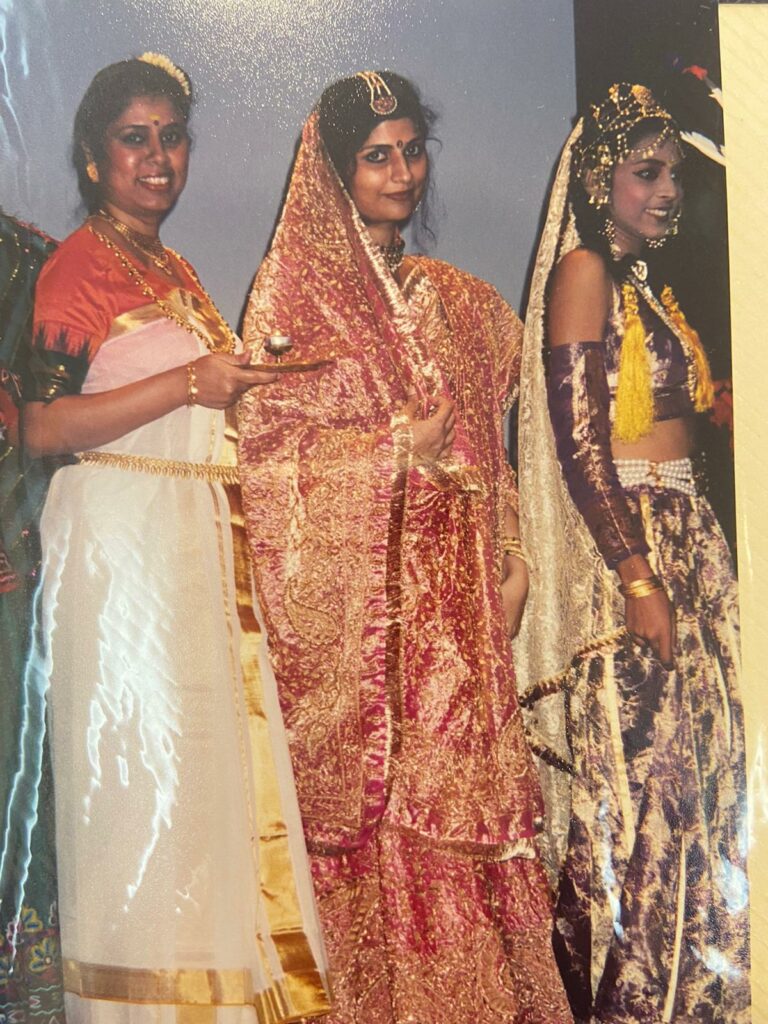

From the 1980s itself, she did many things for the propagation and engagement of arts among Singaporeans for community and country. She made sure culture and the arts were transmitted beyond just Bharatanatyam. I had the opportunity to participate as one of the models for the World Gynaecology Conference held at the Alkaff Mansion where Maami put up a fashion show featuring Pan-Indian outfits from the famed Kala Niketan and she taught how to do the catwalk, weave ourselves around the delegate tables, hold poses and smile and photographed us for a catalogue. When Biddu Orchestra created a fusion performance of Indian contemporary with western music, a few of us performed a fusion piece for the Asian Women’s’ Welfare Association at the Hilton Hotel. I have also had the opportunity to perform on television shows like “Oli Oli” and “Malai Mathuram” on Vasantham. Maami selected me and Lalitha for a tour to Germany organised by the Singapore Tourism Board to promote Singapore. We spent 2 weeks in 5 cities. Maami considered such exposure and experiences as important platforms for Apsaras Arts.

I never felt that language was a barrier during my dance lessons. Maami had an impeccable command of the English Language and tremendous amount of patience, so, although many of the pieces were in Tamil and Telegu, I would script the Tamil to English lyrics – word for word and the repetition of each verse and line and how to represent each word into a dance gesture which would vary at each utterance.

Maami often gave us advice from her own life experiences, some of which I find myself telling others today. “Quit while you’re ahead” was one of her favourite ones. She left the stage when she was 25 when she realised that she had started panting through a performance. She used to say, “I didn’t want people to remember me as a wilted flower. I want people to remember me in my hey-day when I danced for the Queen and recall what I was capable of performing.”

Then she focused fully on teaching. I realise that now as an educator, if you are going to be the show-stopper, you cannot be the teacher and vice-versa. You can’t perform both roles at the same level at the same time. You have to ask yourself if you are going to invest in your student or in yourself. It’s two very different roles. If you are teaching, your desire should be invested in wanting the student to be better than yourself but if you are going to be the dancer, then it will be difficult for you to impart to your student because there is so much of yourself still being worked on. Maami gave 110% of herself as a teacher because she was not the showstopper. She saw her investment in her students. We would perform at the annual Navaratri at Ceylon Road temple where Maami would perform nattuvangam personally even after an exhausting day and not leave you on your own. “Don’t worry about making a mistake. Do what you remember”, she would say. She gave you the confidence and reassurance. Many of these performances and rehearsals would usually end late at night. She always made sure to check and organise transport for the girls and do some car-pooling to make sure they reached home safely. She would rope in mothers and others to help with food, transport and other logistics. That was the care and attention to detail and Mami’s personal touch.

Maami organised many productions in her time. Once every 2 years we would have a major production. I remember being part of Valli Kalyanam, Meenakshi Kalyanam, Urvasi and Aarupadai, just to name a few. Maami would form a committee comprising the big 4 – Mrs Shanta Bhaskar, Kala Mandir (TFA), SIFAS and of course Apsaras Arts. Everyone deferred to Maami in taking the lead but Maami was fair in leading auditions to select dancers and provide opportunities to all the organisations. To bring the arts to the masses means providing opportunities. Even if one child is performing a small role as a butterfly on stage, it could easily lead to 5 family members being part of the audience. When more people get to be on stage it makes the art accessible and more people are engaged in the arts. That was how Maami reached out.

She also made sure the other races were involved. While Bharatanatyam may have a far more deep rooted history and is definitely grounded in theory and classicism, as minorities in this country, we most certainly need to work with the other team players. That’s why Maami maintained good relations with our Malay and Chinese arts counterparts and that offered us leverage and opportunities. From fashion shows, folk dance, classes at People’s Association for lower-income children, she enabled accessibility and affordability. Maami recognised that talent is not always equated with social capital. I felt she was way ahead of the curve and in all my years with her, it’s been more than just Bharatanatyam that I learned from her.

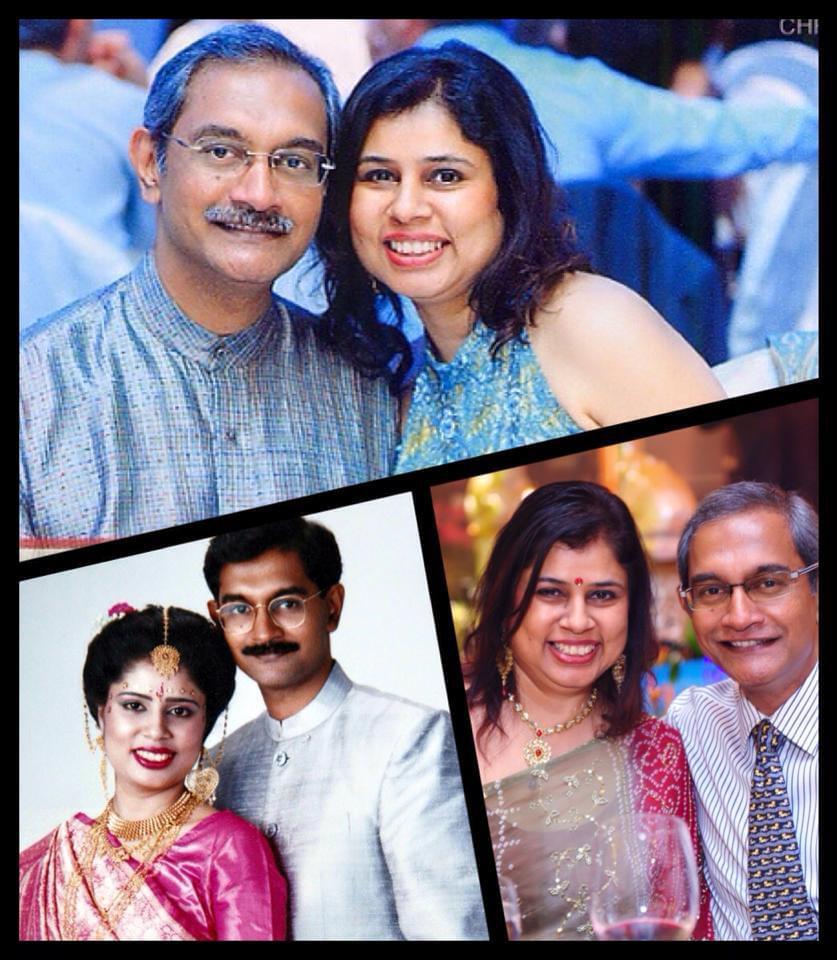

DM: I met Maami as my relationship with Monica was blossoming. She was very encouraging of our budding romance. After my father passed away suddenly, Monica was the first person I called and turned to. That’s when Monica herself realised my serious intentions. In my years training at NIE, I had met many Indian girls there who were culturally entrenched but I was intrigued by Monica’s passion for dance. Her world of Bharatanatyam captivated me and I had never met anyone in our age group who was so involved in dance. I was drawn to her and I used that excuse to meet her at her dance class at Cairnhill Community Centre and I would often sit in and watch. Maami was protective over her girls but generous in allowing me to watch and I am sure, hoping this relationship was going somewhere. I was probably taken in by Monica rather than Mami but over time, I found myself progressively immersed in the Apsaras Arts world.

I started getting involved with the Chingay procession that year and being good with my hands, Maami asked me to create a mermaid shell contraption with lights for a float, and the photograph of it appeared in the Sunday Times! I also helped to create the headgear for a Naga dance on Orchard Road, the previous year too! It was a great way for me to spend time with Monica and it was eye-opening for me to be involved in the arts this way. That’s when my personal relationship with Maami developed. We were like kindred spirits. Maami would often say to me “Menon, you are an old soul in a body of a young man.” And that always registered in my mind. It was something I was grappling with as a younger person, yet mature ahead of my years. I really hit it off with Maami on a personal level. Thinking back to our early courting days, I recall my placing a note on Monica’s table at Towner Primary asking her out for a date and how Monica told both Mrs Sundaram and Maami about it. I can almost hear her voice as Maami told Monica, “Please go… Nice dah. He’s such a nice boy…!”

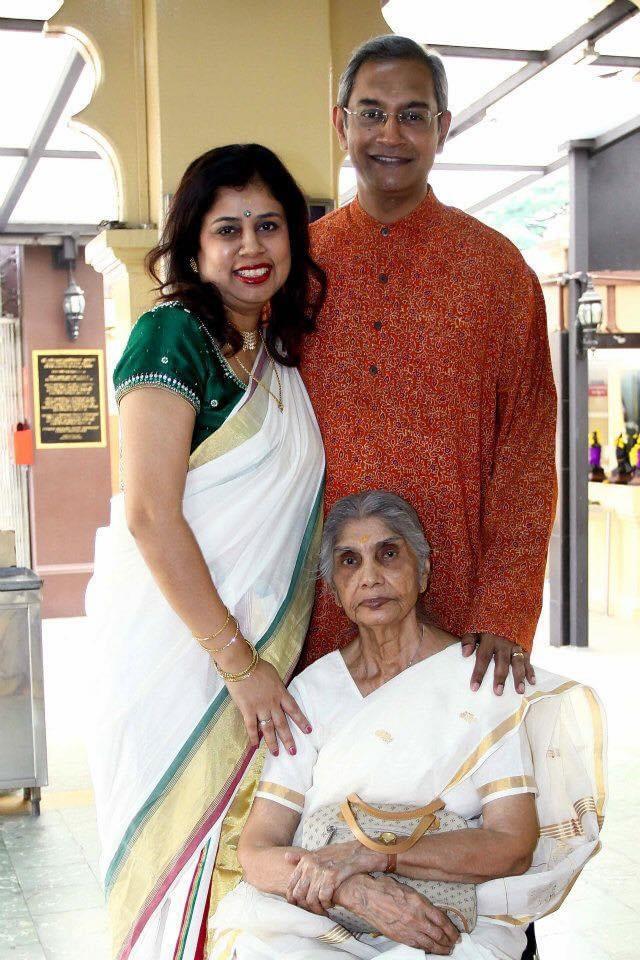

Maami was instrumental in bringing us together. I’ve known her as long as I have known Monica. 31 years. Throughout the years I’ve known Mami, in many ways our relationship evolved. It started casually, then she was involved in many stages – our wedding decorations, she made the speech at our reception, and when our elder daughter was born, she came to our home with a pink silk fabric set to make pavadai-sattai and as the children grew, Monica did enrol them into dance class and they were involved in Mother’s Day performances – Apsaras Arts seniors with their little ones at Ceylon Road Temple. Maami was always a part of our lives. In 2015, when I decided to start my own accounting practice, Apsaras Arts became my first client. Maami was instrumental in this. So, our relationship turned into a commercial one, to safeguard the interest of Apsaras Arts. She would often pull me aside and ask me, “Is everything ok? Are we good? Please make sure that everything is in order. I need you to do that.” She placed a lot of trust and reinforced for me that everything needs to remain above board. As a professional, we are expected to follow certain codes and ethics but it also became more personal. In ensuring that Maami’s interest and legacy is taken care of, the role I am playing now as Apsaras Arts’ accountant has brought this to the forefront. I remember telling her daughter when Maami passed that I am deeply indebted to Maami. If not for her, I would not be running my own business. Maami’s way is to not be obtrusive. She would subtly influence your life, like a cosmic force.

VN: Can you share your memorable milestone in Bharatanatyam?

MSM: My arangetram in 2004 was certainly one. The word “arangetram” is hardly a familiar one in the Punjabi community but Maami encouraged me to be a debutant and show my proficiency in learning. I was already a mother of two and I had just completed my Honours in Applied Linguistics so this the right time for me to take up this project. I decided to combine my arangetram production with doing something for the community. It was called “Voice of Woman – Valar Pirai.” I teamed up with AWARE to raise $25,000 to create a helpline at for abused women. To enable the theme for this production, I approached a few of my contemporaries at Apsaras. NAFA’s studio was brand new and this was the first performance there. We created a mini-dance drama and doing a production like this can be a very costly affair so I was most grateful to the then committee at AWARE who were all extremely supportive.

VN: What is your view about the role of Indian performing arts in society, especially dance education?

MSM: For me, as I said earlier the 3Es are key. [Exposure, Expérience, Expérimentation]. Indian dance teaches you discipline and culture. Like Mami teaches, “If you come for an hour of dance class and learn wholeheartedly, you have fulfilled your prayer for the day. You have surrendered to the divine.” Even with the changing tastes in music and digitalisation, the very act of surrounding yourself with the learning of performing arts and reaping its benefits is timeless.

I question sometimes what happened to the generations of students who learned over the 40 years with Maami. Where are all these students, where are all these talents? I feel the Apsaras Arts net has to be cast wider. Key-man risk should be a concern for the future of Apsaras Arts. The art itself is quite unforgiving regarding age and appearance and doesn’t lend itself to longevity of talents, new showstoppers need to come to the forefront both in the performances and in running the company. Even in a travelling production, people want to see new faces, a fresh cast. The audience also needs to evolve and more should be attracted to watch. We should not have the same people in different costumes! Acknowledging this concern and working towards it is necessary for the sustainability of the company. Yes, collaborations are good but we see the same people trying to create new productions. What about new people reviving old productions? I think sustainability of talent has to be a priority in the long run.

VN: Fundraising and Brand Equity in the arts takes years to build. What do you consider essential to achieve this?

DM: At the core level, the company needs to bring productions to stage that ”wow” the audience and that’s how brand equity is built. I think Apsaras Arts is on the right track for this – with its collaborations, and the innovative use of technology in their storytelling. The need to constantly innovate and keep the audience salivating and looking out for more. That’s where corporate governance by way of reliability, transparency and fundraising comes in. In performing arts, unlike raising money for a destitute child where the cause is clear, people are not going to give money unless they are getting a tangible return. I imagine that for some, the intangible matters, perhaps a brand association with renowned company. To be effective in fundraising, you need brand equity, there is expectation for reliability, transparency and specific outcomes for the money put in. It is not an easy balance. Do you get branding up there first or the governance in place first? Without governance, you can’t get money for your productions because you need to build trust. If your productions are not up to scratch, why would financial support be given if nothing credible is created? This is a very delicate balance. To pump in money, people need to be cultivated over time to donate and build support. Creating credible productions are key – to have the “wow” factor, that’s an intangible essential to brand equity. Governance can be built structurally bit by bit. Apsaras Arts has it but needs to capitalise on it to build on it and people become more willing to donate.

For me, culture is a bridge. The sad thing though from an intra-culture perspective in Singapore, you hardly see the North Indian community turn up to watch South Indian classical art forms. And interculturally, how many non- Indians do we see at our performances? The average Chinese or Malay person in Singapore, how much do they know about Indian culture or Bharatanatyam for that matter? The awareness level is very low. The significance of our cultural performances is substantial but has it transcended to greater understanding between cultures? Our society is still very fragmented and to me that’s where the cultural aspect of dance has probably failed.

MSM: Perhaps the solution is in the marketing of the productions to reach out to more new audiences. Maybe some hybrid performances are needed. Having a great performance is fine, but how do you draw in new audiences? We need to lend ourselves to the other audiences out there. Even with digitalisation, how many can understand core Bharatanatyam pieces nowadays? Even if it’s not full Bharatanatyam, to explore semi-classicism with Hindi music is an approach Maami had used to reach out.

DM: Anjaneyam is a good example where the use of South-East instruments and Javanese dancers gave it a larger appeal. So that’s inter-cultural but what about intra-cultural? The north-south Indian divide is still far too great and the North Indian community should be our primary natural audience and donors.

MSM:In fundraising, there may be people inclined to support a talented albeit disadvantaged student to learn and perform her arangetram. This becomes a tangible specific goal over the medium term that enables a milestone achievement. This might appeal more than a blanket donation and donors know where their money is going. E.g., I used to donate to help girls in India who want to get a teaching certificate as I wanted to empower girls. So as a result of my own vested interest, I wanted to see the progress of this student, and that kind of donation to support a self-sustained woman appeals to me. Similarly in Singapore, it would appeal to me to help a student who can’t afford to pay to learn or can’t afford costumes or temple jewellery for Bharatanatyam. Donations are important but it would help the donor if the cause or initiative is specified.

DM: Fundraising is about sponsorship and donations. For sponsors, the specificity is inherent but for general donations, it should be for a worthy cause without having to know the details of how the monies will actually be used. The decision to donate and the quantum is based on trusting the company and being familiar with their past track record in creating fantastic content. So, the attitude is “Do what you will, we want to see you sustained and continuing your good work.” That’s why the structure of fundraising needs to be dynamic.

VN: How do you think Apsaras Arts, the company has evolved over the years and where do you think it’s headed?

DM: From 2015, I’ve seen the company become more corporate in its outlook. For a long time, it was like a cottage-industry set up. During Maami’s time the creativity was always cutting edge and rich in content. The innovative content remains the cornerstone of the company – to collaborate, to weave in unusual elements creating unique works. That’s been Maami’s influence. She never sat on her laurels and she always thought out of the box. I see that growing more now with the collaborations, experimentations in the productions – the breath and depth of it which is a very positive evolution. The entity is structured, corporate governance is entrenched and the company has a charity status. It has matured as a company. It is no longer run out of a basement or community centre or out of somebody’s house. It is a tangible business with a positive, viable outlook. For me, that is testimony to how the company has evolved.

Aravinth has brought in his commercial expertise. He is a very rare animal with a strong artistic vein in him while being commercially savvy. Given his work experience, he is bringing that into the dynamics of this business. He is looking for ways to grow the company and be a formidable business entity not just artistically but to be commercially viable. Traditionally, Maami had put up extremely high quality and memorable productions but it’s unclear whether they made money and if there was an intention to make money. I often think it was for the love of the arts. That continues now but I also see it is leaning towards paying for itself and giving a support structure for those within the company. Historically, I imagine the many involved were volunteers, as I was, and probably donated to support the company. Today it provides a living for the artistes and that’s a significant step forward. It shows that this company has evolved, has thrived and is able to provide sustenance for the people within it and the wider industry.

The perennial concern with artistic people is of course, there is often a lack of attention to detail. For that, the professionals are hired. That’s why someone like me and you are there to provide the balance to keep the business afloat.