By Vidhya Nair

VN: How did you come to be introduced to the Satyalingams & what were your first impressions?

UR: I met them both soon after they arrived, probably 1974-5 at an Air India party (her husband Rajan was Reservations Manager with Air India at the time). Both Neila and Sathyalingam were of course much younger and my first impression of Neila was her open smile – halfway between a smile and a laugh. She was warm from the start. When she recognised that I was a student of Pandit Chokalingam Pillai (nephew and Guru of lineage of the legendary Pandanallur Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai), she made an instant connection with me. Satyalingam also remembered me from my Arangetram in Chennai back in 1954. It turned out that he was present at that recital. A lovely coincidence!

I saw Neila as a typical Ceylonese-Indian family woman who spoke Tamil with the Ceylonese twang. Sathy (Satyalingam) at that time was a silent person, half-smiling and he would speak Tamil in the Indian way. We were in sync in every conversation and able to speak on many topics and have an opinion. We often talked about the arts and gelled on a big factor – her son, Skanda. I was Medical Director for School Health at the time and Skanda was a multi-disability child who needed total care and attention. Most importantly, I helped her write the first letter to MOM explaining the needs of the growing boy and his teacher-mother and why a male caregiver-helper was needed. I had tremendous respect for her in how she managed his care. Both Neila, Sathy and their daughters treated Skanda like a normal child and that was more than half the battle won. They needed a male caregiver for Skanda to move forward in their life in Singapore. After many queries from MOM, they received approval for a male caregiver from Srilanka, who was familiar with their needs and culture. Over the years each caregiver stayed for a number of years meeting the needs of Skanda and their home. It was then that Neila was able to free up her mind and channel her energy, talent, knowledge and skills to developing a new circle of artiste friends and make contributions to the arts scene in Singapore.

We also gelled on the fact that my son, Sanjiv and Neila shared the same birthdate, – February 8th. My son and she would exchange annual birthday wishes and speak to each other on that date. She was terribly upset when I was widowed and we often reflected on our first meeting when she met Rajan. She had noticed then that I had placed a rose at the nape of my neck in my hair the same way she also did too. We clicked, not realising how close we had become over the years but that’s how it was – a strong emotional bond based on our shared love for Indian classical music and dance, the medical care of her son. Managing our family and home – for me, she was like my family!

VN: How did your relationship with Neila evolve over the decades? Share your thoughts about how you saw her develop her art in Singapore?

UR: Neila wanted to start giving dance classes. She had a special talent for teaching little children. She first started classes at Handy Road (behind Cathay Cinema). My daughter, Rekha joined along and so did a few other mothers who sent their daughters. My son would come along too. It was a very simple, single room with a stage. She taught basic Bharathanatyam for children and Sathy and daughter Mohana gave her the background music support. Over the years, my mother, Mrs Sharada Shankar an accomplished violinist, also came forward to join Sathy, Mohana and their troupe in their Carnatic music recitals at various venues in Singapore.

The way Neila started in the arts scene was gradual, a step-by-step move up the ladder. She started classes at Cairnhill Community Centre and then at Tanglin Community Centre. I remember when the Minister for Law & Member of Parliament Mr E W Barker came for an event there to present certificates to performing children, he commended her on her work at Tanglin CC. It was a step into her future work with People’s Association. At Cairnhill CC, she moved towards inter-ethnic work collaborating with other leading dance veterans, Mdm Som Said and Mdm Yang Choong Lian. This resulted in the formation of Little Angels – a multiracial children’s dance troupe. Neila wanted the children to participate in a folk-dance competition in Europe and she needed help with the funding. I’ve always believed that it is easier to seek a small amount of funds from a larger number of donors than one large amount from a single donor or sponsor. I managed to help her achieve this and we sent them to Europe. They came back winners and that was a significant feather in her cap and inter-ethnic dance became her mainstay. This is an important criterion for the Cultural Medallion (highest culture award by National Arts Council which Neila Satyalingam received in 1989) She built a little fraternity there and also at the Kamala Club on Moulmein Road (near the Indian Association). She was appointed as People’s Association’s choreographer while based at Cairnhill CC and received much needed support from them. She had an innate talent to link the artforms and the ability to respect and get along with the other ethnic group champions. They were like sisters – not commonly seen. It was not competition at all. It was them, coming together, moving up hand in hand, benefitting each other so that none were left behind. Their contribution was in the right direction.

When the National Arts Council was formed (in 1990), I was nominated to be a Council Member along with Prof Bernard Tan, Brother McNally. Mdm Kay Kuok. Mr Robert Lau and other leading community arts champions under the leadership of Prof Tommy Koh and later Mr Liu Thai Ker. Serving on the Council in those years was a real privilege as I had the opportunity to interact with these brilliant minds and true culturalists. I also had the privilege of serving on a number of committees within the Peoples’ Association e.g., Lifestyle and Lifeskills and was also Advisor to the Singapore Indian Orchestra. This gave me the perspective and overview to see the arts companies at the national and community levels and engage with individual artistes and watch how performing and other arts was developing in Singapore. As we mapped the direction of the Council, we were also able to identify those men and women who had achieved appreciation of their peers as well as the leading arts industry veterans and champions. They represented their community and the nation.

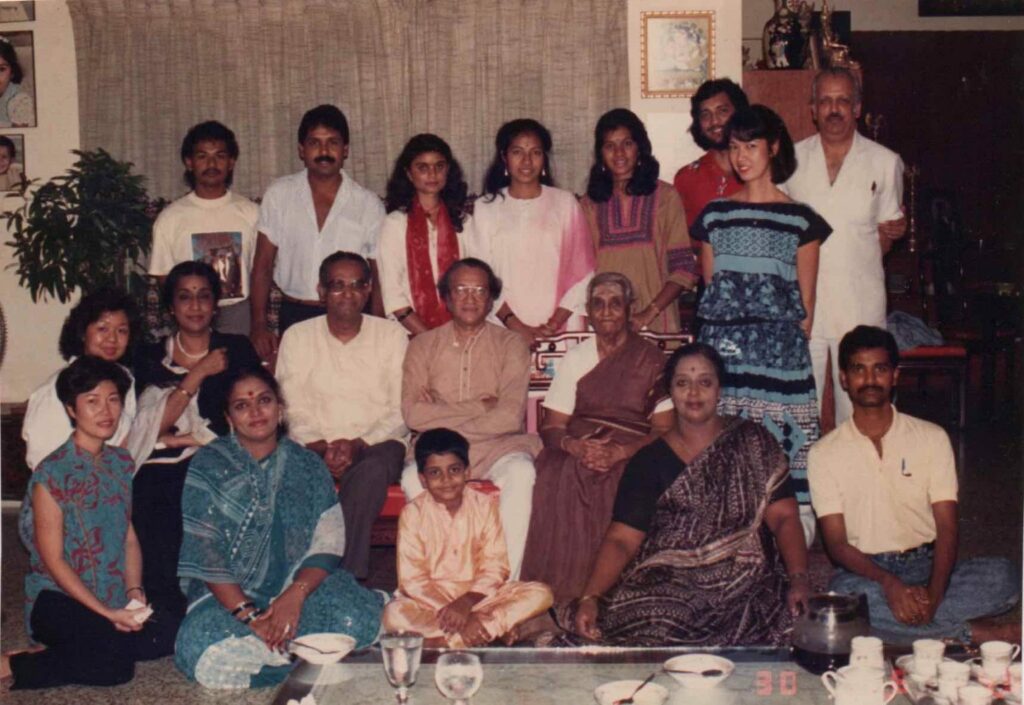

As Neila moved from her first apartment in the Orchard area to house on Sarkies Road, I remember admiring her collection of artefacts related to Indian Dance and Music. It also became a venue for the Sathyalingams to host visiting Indian artistes such Pandit Ravi Shankar. Of course, the evening was noted for the fantastic Indo- Ceylonese spread Neila would churn being the great cook she was. Such evenings also brought together Singapore’s inter-ethnic arts community and the overseas arts fraternity to exchange thoughts and ideas and share experiences.

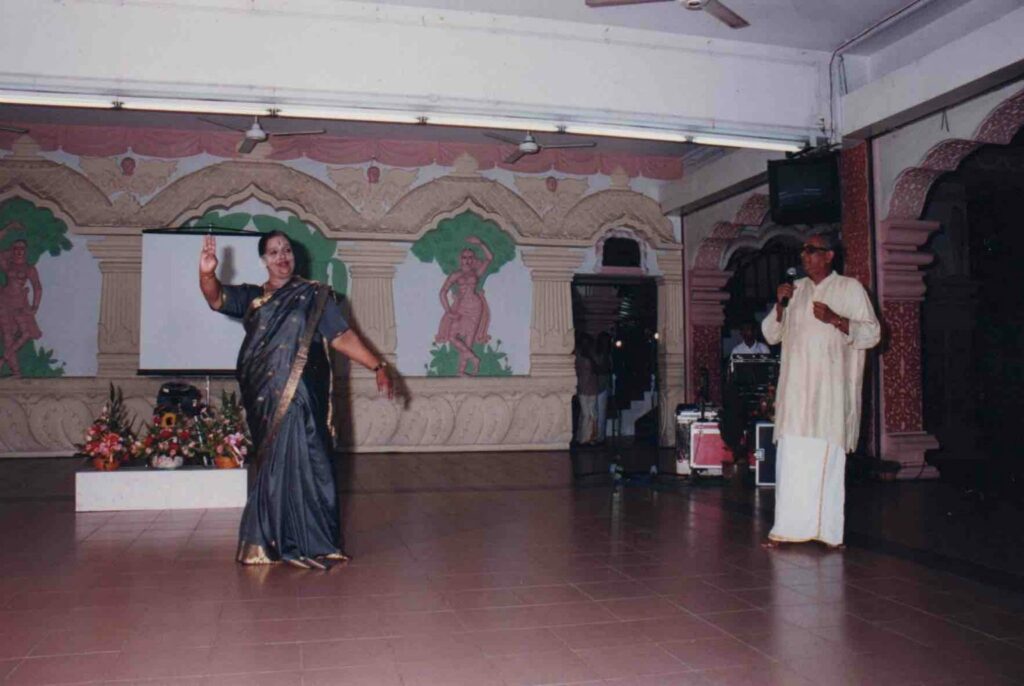

In those years, I had become an active stage presenter – providing the link between the audience and the artiste. I used to insist to not be called an emcee as I wanted the audience to appreciate the art and wanted them to crave and return for more. After every show, Neila would ask for my feedback as she felt I would be frank and give her a constructive critique. She loved to put all her little ones together on the stage for an item as she felt that was what the children and their parents would appreciate. It was of course fun to see kids performing as even the mistakes they made would be taken sportingly. I used to advise her not to do the same with the older students as they would draw negative criticism if they made similar mistakes and were not well coordinated. I used to pull her up when she did that and she accepted it with respect. She knew I wanted her, as well as all other Indian dance teachers in Singapore, to target reaching international standards of professionalism in presenting their art form. Ballet was already far ahead. Malay and Chinese dance were building up their competencies. The quality of dance is an important criterion in grant funding support. With back-to-back performances, comparisons are not incidental. Among the Indian dance schools the Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society and Bhaskar’s Academy were well established by the late 1970s. The Temple of Fine Arts (TFA)was established in the 1980s and they started presenting stage shows with a bang. These were not ticketed shows but based on donations run by volunteers from every category of service including leading professionals who designed elaborate sets. Sound and lighting along with IT support. Fantastic, huge theatrical style productions which made an impact on our audience. At the time, the quality of shows by TFA was top notch. Neila had not yet reached that standard yet. While she was trying to focus on developing the art, TFA gained a footing with their enigmatic leadership in Swami Shantananda and the energy of all the volunteers and many creative people.

Nelia’s ambition was kindled. The group ensembles became the norm, perhaps influenced by Chinese and Ballet dance. I recall the launch of Vanda Ms Jouqiaum – the Singapore orchid. Neila used ribbons and purple costumes in her segment. She was increasingly embodying the Singapore spirit and that was her edge. She was seen on par with all the other dance forms in Singapore. Sathy would discuss the music with me and I would constantly tell Mohana (their daughter) to not turn away from the mike when she sings. Neila would scold, “Listen, listen to Uma….” When she needed help or advise, she would call. Similarly, I would call her if an item was needed when I organised shows and will tell her frankly if there is a payment or how long the piece should be. I kept advising artistes and arts groups to learn how to draft the Budget – the Income and Expenditure including getting quotations from vendors and most importantly, ticket sales are to be strongly encouraged. I found myself imploring organisers to please pay artistes the basic costs so that artistes did not have to pay from their pockets and she appreciated it very much. For dance, money is so important as items like music support, costumes, props, sound, lighting, etc are expensive. Dance would often get small amount from organisers and funds would often be inadequate. Neila learned this along the way with her experience with PA. Funds continue to be a problem to date.

She wanted to develop many high calibre dancers who would execute the art well, meet the needs of the community and reach the call of the nation. Neila groomed many dancers but at that time, turning professional was still not a viable financial option but she nurtured a number of strong hobbyists like Dr Roshni Pillay and others. We had started to see more Arangetrams from all Indian teaching Academies. I tried to attend as many of these performances. With Neila, I felt I owed it to her for frank, constructive feedback on how she showcased her ensemble, programme content, the music, dancer’s abilities, colour choices & costume design and. She took my feedback sportingly.

Around this time, her children – the 2 older daughters married and moved out. She also transitioned into a different age group and her health started to give her problems. I would constantly be telling her to manage her weight. She would exclaim, “I do not eat!” and I would ask her “Do you move?” It was difficult for her to manage her own health, family, expectations in the community but she never gave up on her art. She had an extremely dedicated set of students who have been with her through thick and thin and helped her bring Apsaras Arts to where it is today. They were regular performers, helped with make-up, supported her in administration. There were several male students who helped her with logistics for the shows – transport, food. All of them started to become part of her family and she shared with them her vision, her dreams as she was considering their future and didn’t want to lose them. Some of them are still with Apsaras Arts today She very innocuously began to prepare and plan for the next generation.

VN: Transition in Apsaras Arts. What were your early impressions of Aravinth – the artiste and then the artistic director of Apsaras Arts?

UR: When I first met Aravinth back in the 90s, I considered him as a Veena artiste. He was concurrently a regular live and television Carnatic performer. His Young Artist Award (in 1999) recognised him for his contribution to music and as a veena player. He worked and performed with other arts groups – Bhaskars Academy and TFA.

Satyalingam recognised his talent. Aravinth was one of the few Srilankan Tamil artistes who made his mark in the Indian music scene in Singapore. He spoke Tamil with a Srilankan accent and was a knowledgeable South Indian musician. Another important part of him is his IT knowledge and I turned to him for IT advice for one of the nursing homes I was working with. For many years, Neila was up in front then slowly she started to take a step back and others came forward progressively to share in her responsibilities. Neila started to delegate her work as there were great demands for performances and her physical health was not permitting to cope with the demands of her marketing efforts. She never said no to multiple performance requests. I remember when we worked on Chingay together, we had the opportunity to walk through the parade side by side at Orchard Road and in the Stadium representing our Indian community. These are efforts that won people over and Neila’s contributions had gained tremendous attraction.

I started to see Aravinth then as part of Mama’s music entourage. He came to be prominent in the planning of their events and would be the spokesperson. When the company was set up (in 2005), it coincided with other groups also seriously considering how to set up a dance company. There was an industry wide realisation that via a company, with a sufficient talent pool, the artistes involved could start to make a living with income from shows. Creative thinking is intrinsic to such an endeavour and the people who can deliver the vision came to be needed. I saw Aravinth with his already established relationship and bond with Satyalingam and Neila move forward to become the bridge for Apsaras Arts to build their vision and become the pillar for both to lean on. Like Satyalingam and Neila, he too was from Srilanka and received his arts training similarly like them in both Srilanka and India. They had the same roots, culture and understood each other well. They were able to share ideas and with his IT background, he also brought his resources and network. Together with Neila’s PA inter-ethnic community, they were in a very good position to perform for anybody and everybody. Whether it was the Ceylon Road Senbaga Vinayagar Temple or Embassies or multi-ethnic organisations, they came to receive greater prominence and recognition. Apsaras Arts were not exclusive. They were inclusive.

Aravinth started to bring in and involve more of the foreign Indian talents which included acclaimed Indian artistes and he recognised the budding talents emerging from the new Singapore Indians who had learned, grown up and settled here. The beauty of Neila and Aravinth was their ability to gel with these incoming talents and find ways to harness this new knowledge and skill to coordinate and collaborate and build resources – costume design, music and other stage craft capabilities in dance. IT was replacing sets and props and with Aravinth on board, Neila was able to realise her vision in her own style. This was seen in the use of much-loved and revered Indian composer Rajkumar Bharathi for her projects. He worked very well with Apsaras Arts and his music compositions helped transform presentation of epics like Ramayana as done with “Anjaneyam” in 2017 to a level that appealed to international audiences.

Travel to India became a very big feature as we saw how routinely Apsaras Arts went to perform at the Chennai Music Academy and other key venues in India. Aravinth saw Apsaras Arts in a different light. He brought a modern, international style of theatrical productions which was a sudden change in our Singapore Indian Dance scene. He started to create productions with a theatrical concept in the newly minted venue – Esplanade, Theatres on the Bay. He was able to see the dance ideology that Neila had but he realised that he had to present it in a fresh, innovative way. The art and company had to evolve to meet the demands of today’s technology and audience. The time had come for Aravinth to move out of IT and take on the responsibility of running the Apsaras Arts company. The support from the various Grant Schemes of National Arts Council over the last decade also played a role. Grant proposal writing is an important skill. It calls for a mission, vision, planning and adherence to delivery and reasonability in cost management. Aravinth writes and speaks well and he presents good visual proposals. He developed concepts beyond the Indian texts and history – he brought in the concept of temples showcased through Indian dance which linked all the South East Asian countries. He identified concepts like architecture which resulted in great positive response and accolades. These are areas of interest to many people. He touched the right chord and pushed the art forward.

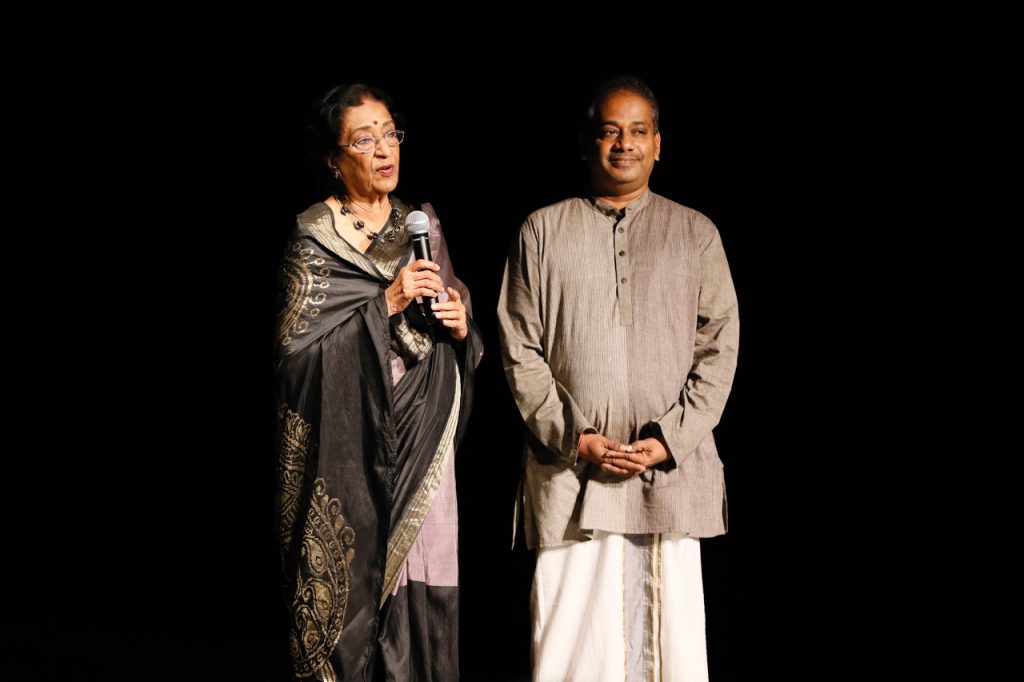

Aravinth has been able to recruit new talents and create his own platform and raise standards which he now needs to maintain. The coming of Mohanapriyan has aid Aravinth to stand alongside other international names like Akram Khan, Mavin Khoo, Wild Rice and others. Mohanapriyan came (in 2012) and boosted Neila’s courage and interest because she saw in him – a dancer from Srilanka, like herself albeit a male dancer in physic and form. He spoke the same language, culture and had the same arts training background ably straddling Sri Lanka and India just like her, Satyalingam and Aravinth. She could treat him as her own. I think she found in him the child she may have lost out on, maybe. For Satyalingam, it was already Aravinth, the son they leaned on to help them administrate and set direction to their lives. The coming of Priyan fitted in beautifully with Aravinth. I remember Neila telling me in Tamil of Priyan, “You saw what kind of child has come for me?” I’ve always felt that its God’s grace that brought Aravinth and Priyan from Srilanka to the shores of Singapore.

VN: What is Apsaras Arts to you today?

UR: UR: The spirit of Neila and Mama has been imbibed by Aravinth. As he moved forward with them, having understood their thinking, he went a step beyond to take the art form to a level that is required today in meeting the expectations of the artistes Neila trained. In meeting her ethnic requirements, he has put her on the international front. For Neila, who was so full of life yet was so traditional, this was a fitting way for her company to evolve after her time.

With modernity, everything needs a relook. Today, less is more. The costume, jewellery and headgear should not distract from the art itself. Music has become more interactive and more dimensions have been added. The Aravinth-Priyan dynamic can see the artform as a traditional and modern form which can capture the imagination of the younger generation irrespective of nationality. Whether performing in South Africa or France, the audience can feel the emotion of a performance without prior background or knowledge. I think Apsaras Arts over the years, is a name synonymous with South East Asian culture. It represents beauty, the feminine touch so the name is familiar even for a Western audience. They need to build on this more and more.

VN: With your many years of experience in arts management, how is the classical arts scene today?

UR: I think there is a huge difference between music and dance. Dance has evolved on the stage, there are more performances, more groups but the content is still reliant on history and mythology. There were a few attempts to deal with social issues but that didn’t hit off well. Social issues don’t gel easily with the classical format, the compositions don’t transmit nor does the form although costumes are simpler.

In music, we see a great move towards the creation of fusion. We see many new innovations in Carnatic music with groups in India like Agam, Thaikudam Bridge, and in the diaspora especially with Indian Raga and singers like Abby etc. The digital platform has brought global accessibility and in Singapore, the talents of the new Indians has resulted in many indoor home performances both in Hindustani and Carnatic music. So, music is escalating in the community but shows are mostly online. Dance in Singapore, we see arangetrams and we see trends of live big shows by groups [ with NAC grant funding]. The Blackbox is a new concept, easy to organise infrastructure but these shows should limit themselves to a crisp 60-90mins because audiences can’t appreciate a longer format. In Singapore, I find the audience is quite savvy with what is trending and available online. They are able to discern and compare. For example, Abby has so many fans and his 73 ragas format is so well put together and cohesive. The pandemic has pushed the demand for art which makes it far more competitive and challenging for artmakers to exceed expectations. I still don’t understand how digital content is funded though. Yet, we see the willingness to pay for art is woeful. There should be a minimum payment for any art. This is the sad story of the arts. There is disdain for big arts groups who get funding but the truth is, if they are able to justify their grant needs in writing, they will get it. You have to know how to write. It is a tremendous period for the arts to blossom. Many opportunities to get creative, experiment and stay current. Music can be adapted for any situation, mood. Also, the diasporic young Indians have raised the bar in standards and we may see a reverse trend in who the best artistes in classical music are. The finance part of it makes it difficult to survive so although quality of music and dance has gone up, post pandemic, we may see a dip in standards. Will there be enough artistes to cope with the demand and standards to meet audience expectations? We will have to wait and see.

VN: What is your concern for the future for the Indian arts in Singapore?

UR: My biggest concern for the future of the art is its financial viability and sustainability. Today the financial model for arts financing has become extremely complicated. With greater need for transparency, accountability and audit checks etc – drafting a budget and managing expectations on the cash flow has become more important and more time-consuming than the show itself! Often, we see people who assess arts financing have no background how the creative process works – who are the go-to talents in the industry and how cost is dependent on innumerable factors. Negotiating costs for a show requires experience and know-how. Getting 3 vendors quotes for every artiste / arts group selected especially leading artistes is not feasible as the choice is of that particular artiste. You need volunteers and staff who know the arts and the financial requirements. They need to know how to scrutinise and query every vendor selected, running background checks from the start very professionally without affecting the morale of the artistes.

The arts are also dependent on volunteers to organise and support artistes and performing groups. To encourage more people to support the organisation of events which involves performing arts, the environment should be conducive. “Conflict of Interest” can be a red herring – there should be declarations on financial interest but in the arts, relationships and bonds are equally important and trust is often only built after years of collaboration, support and mutual respect. The arts ecosystem in Singapore should help to support artistes and performing companies to cover their costs and sustain them to build on their work. It should also be a nurturing space for arts volunteers to work for the betterment of the arts bringing their organisational skills and these volunteers should not be hamstrung with bureaucracy. This will only threaten and dissuade people from supporting and volunteering themselves to the arts.