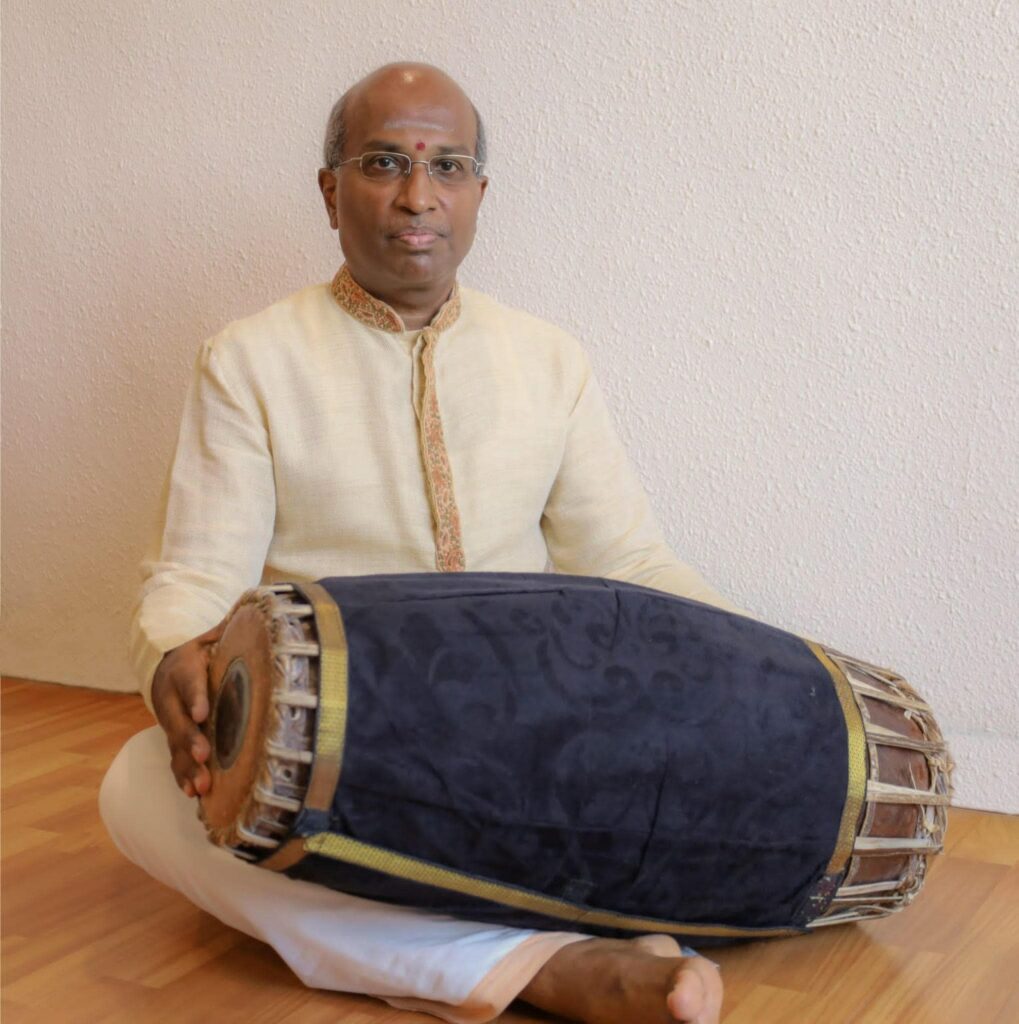

An Interview with Thiruchittampalam Ramanan, considered the Pride of Singapore, a mridangist with over 1500 programmes, in his kitty : By Vidhya Nair

Let us start from the very beginning. Tell us about yourself and your family

I was born in Malaysia in the 1960s. My father worked for the Malaysian railways and married my mother who was based in Singapore. Eventually, our family settled in Kuala Lumpur (K.L) where I studied before permanently moving to Singapore in the 1980s during my teens.

How did you come to be introduced to Carnatic music and the mridangam? Who nurtured your interest?

It started with my maternal great-grandfather, Arumugam. He loved Indian Classical music. After he heard that the Music Academy was opening in Madras (now Chennai), he quickly relocated himself from Malaysia to Chennai in the 1930s. He bought a house close to the Academy so that he could attend concerts regularly. He made a serious commitment to study and learn as much as he could.

As a retiree, he pursued this knowledge by befriending all book publishers ensuring he would receive the first copy of the first release of any book in the Carnatic Music genre. This resulted in him having a huge collection of rare and acclaimed Carnatic music books. Subsequently, much of his collections were donated to the Music Academy Library in Chennai. He also named his child, my grand uncle, after a famous music composer, Saint Tyagaraja.

Although the ancestral roots of my family began in Jaffna, I only visited Jaffna when I went on tour with Apsaras Arts six years ago. A Shiva temple connected with my family still stands in our ancestral village there. I met my wife, Sarada when we were both active in the Singapore Indian Orchestra & Choir (SIOC). She sings and also plays the violin, veena and sitar. My two daughters are also pursuing Carnatic vocal and my elder daughter learnt Bharatanatyam. I am grateful to my family for supporting me to pursue my passion in mridangam.

How did you come to learn the mridangam? Tell us about your early learning and teachers?

From a young age I was exposed to both Carnatic music and Bharatanatyam. My mother and her sisters learnt both art forms from early classical arts stalwarts of Singapore. They were the pioneer batch who learnt music from the late Pandit Ramalingam together with Vijayalakshmi Sharma and the late V Ramachandran. They also learnt Bharatanatyam from the Bhaskar’s. My grandfather, Dr Balasingham, a pathologist was a patron of the arts and was instrumental in helping K P Bhaskar to perform in K L back in the 1950s. In the early 1960s, my father was posted to Ipoh where he was the President of a local temple. He had the opportunity to learn mridangam soon after he arranged for a mridangam teacher to be brought to Malaya from India. I was drawn to my father’s mridangam at home and used it to accompany my grand-aunt who would sing at home. I was fascinated by its dynamic sound and my interest developed in this nurturing environment. My father further kindled my interest in mridangam by taking me to concerts regularly. I recall watching Madurai Somu and Dr Balamuralikrishna when they performed in K L in the 1970s. We would try to meet the musicians and interact with them. I began learning formally at the age of 12 under a loving guru Thangavelu Vattiyar. In 1980, Flute N Ramani came for a concert in which Karaikudi Krishnamurthy accompanied as a mridangist. My father and I met them and I insisted that I wanted to learn from Krishnamurthy sir after hearing him play. My family encouraged me to continue taking lessons from him throughout my school years. My elder sister became a full time Bharatanatyam teacher with Temple of Fine Arts, Kuala Lumpur till today. Our family treated this pursuit as a divine art, a gift to be nurtured and supported. Several members of my extended family have gone on to pursue music professionally and are promoters in Kuala Lumpur, Perth and elsewhere.

Karaikudi Krishnamurthy, your teacher. Share with us your learning years with him?

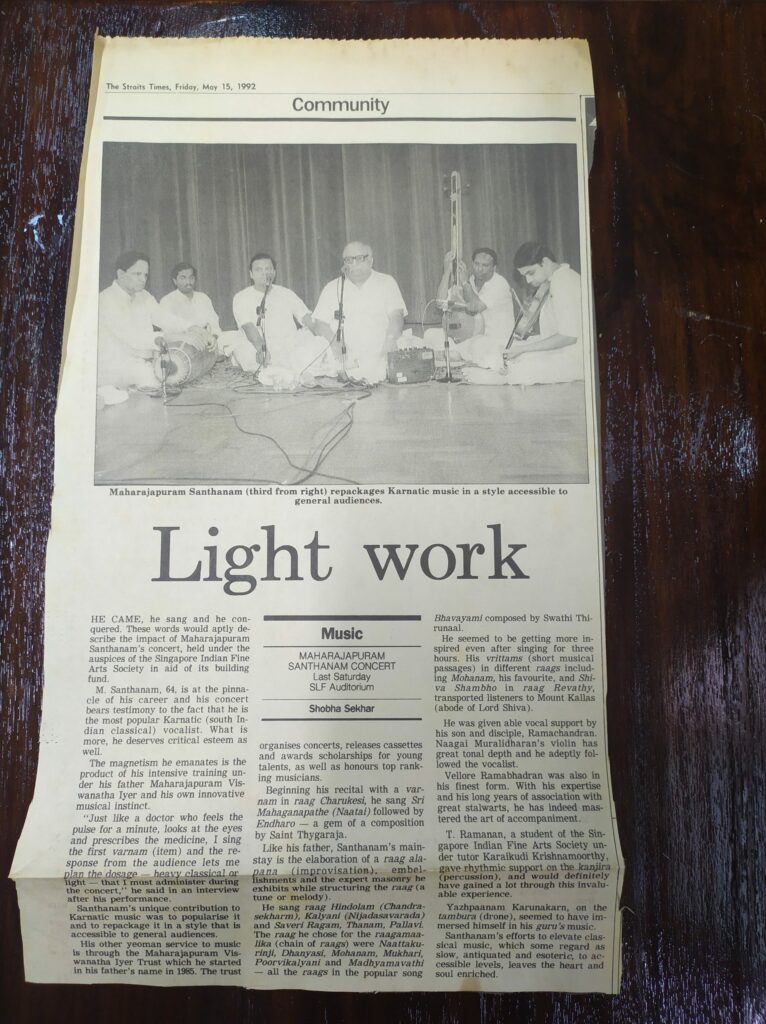

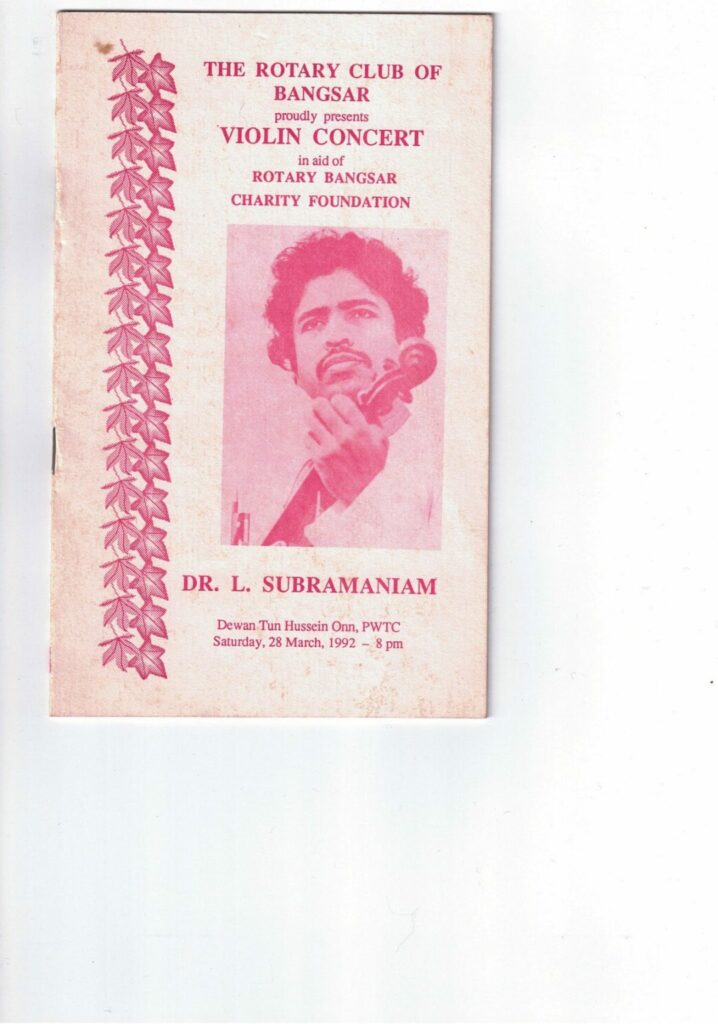

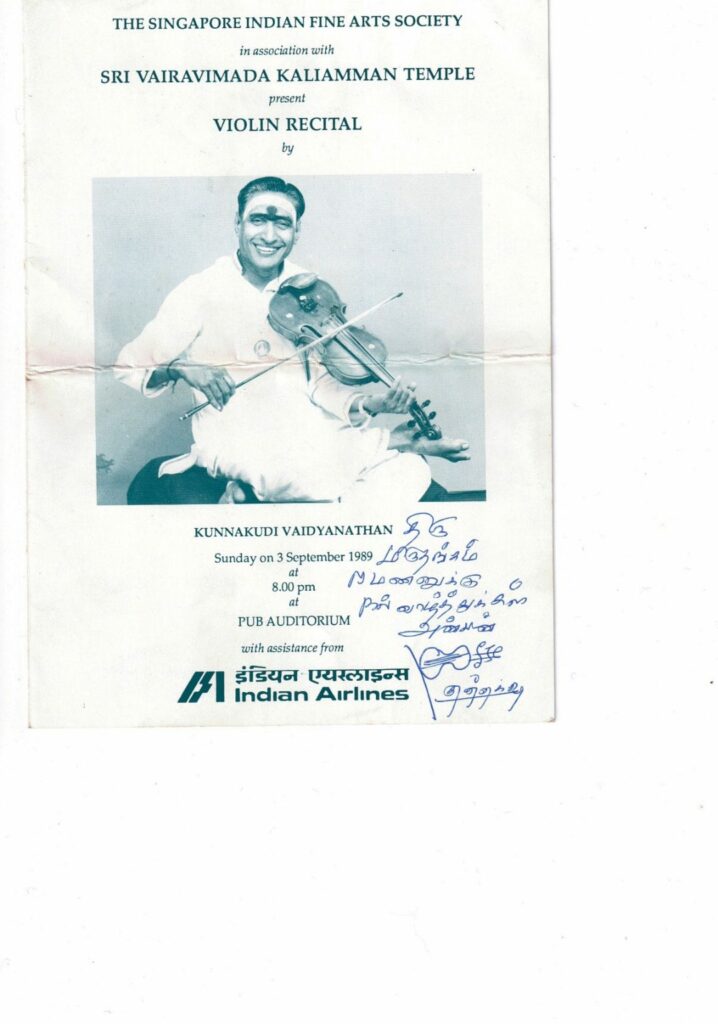

When I met him in 1980 post concert, he told us he had just taken up a position in SIFAS and asked me to take classes there. My father agreed to send me to Singapore. As my father was a Railways employee, I could get free train passage. Initially during school holidays and weekends, I would take the train down on my own and attend Krishnamurthy sir’s classes. As a mridangam student, I would have classes for long hours throughout the day and eventually stayed with sir. He cared for me like his own son and was very loving. SIFAS was at Norris Road then and there weren’t too many students. I was fortunate to meet many Carnatic music stalwarts who performed in Singapore including artistes like K V Narayanaswamy, M L Vasanthakumari, T N Seshagopalan, Dr N. Ramani, Dr L Subramaniam and many more.

Krishnamurthy Sir was an amazing and dynamic teacher. He taught spontaneously. He organised many programmes himself and was an active performer both in Singapore and Malaysia. He created korvais in impromptu and taught them along the way to a concert. He expected me to perform what was taught even at these last moments. Over time a group of us formed, my peers were Paskaran, Selvapandian and Devarajan. As I was often called on to practice and perform very regularly, I realised I was in a unique position. Upon Krishnamurthy sir’s insistence, I was exempted from paying fees to SIFAS. I learned under him till he left Singapore in 1988. Apart from playing alongside him on Ghatam or Kanjira at his regular concerts, I was often encouraged to perform as a solo accompanist. Every experience was a lesson in itself. As his live-in companion, he cooked and took care of me. He knew how to motivate; give you challenges and keep you on your toes to be ready to perform at any time.

I recall in 1983, he organised a concert for Karaikudi Subramaniam, an acclaimed veena artiste who also edited Rishabham & Gandharam, the second and third edition of SIFAS’s Carnatic music textbook [He is Krishnamurthy sir’s cousin, belonging to the Karaikudi lineage of court musicians and thereafter faculty at Kalakshetra]. I was informed that I was to accompany him an hour before the concert. Similarly, vocalist Madurai G S Mani was scheduled to perform in KL in 1983. For some reason Krishnamurthy sir couldn’t travel. He told the organisers that I would go in his place. T

hat concert remains in my memory because of G S Mani’s generosity and encouragement. Till date, that was the longest Thani Avarthanam I have ever played, close to 40 minutes. In 1984, I played my first concert in Chennai during the afternoon slot of the Music Season at the Madras Music Academy. I performed here again in 1987. Krishnamurthy Sir was a regular performer at various Sabhas including kutcheris in Singapore with prominent artistes. He would insist his students perform on stage alongside him. This allowed me the opportunity to play the kanjira or ghatam, giving me a variety of platforms and a great deal of exposure. I was privileged to play with accomplished artistes like Palghat Raghu, Umayalpuram Sivaraman, Vellore Ramabhadran; all well-known percussionists who made me feel at ease whilst performing. These accomplished artistes had the ability to compliment my playing style based on my strengths. My own creativity and flair with the instrument developed at this time. Child prodigy, the late Mandolin Srinivasan also performed in Singapore and I was privileged to accompany this gifted artiste and followed them to K.L as well. Over the decades, I have accompanied Alleppey Venkatesan, Trichur V Ramachandran, Charumathi Ramachandran, Sudha Raghunathan, T M Krishna, Unni Krishnan, Sikkil Gurucharan, Akkarai Sisters and many more.

Tell us some of your favourite aspects about this instrument and what it takes to gain mastery in it?

Apart from just being a percussion instrument, the mridangam is in itself a musical entity. It’s tuned to a certain pitch and the tonal qualities it produces is amazing. At any kutcheri or dance program, we can say that the mridangam is the heartbeat of the performance. It has its own complexities and over time the mathematical permutations have only intensified. Complicated theermanams. The making of the instrument has also evolved. Traditionally, it was made from leather. Maintaining the pitch in an air-conditioned environment is a significant challenge. Nowadays, mridangists use the bolt and nut system to adapt to pitches. Sections can now be removed for repair and tuning stays longer.

How have you maintained the standard of your playing skills over the decades?

I have continued my learning with Krishnamurthy Sir even after he left Singapore for good in 1988. He continued to visit Singapore regularly and in recent years, he records new korvais and sends them over for practice. After learning from him for almost a decade and the close bond that we share, it was difficult to consider learning from anyone else. He’s 83 today and keeps in good health. I never miss speaking to him every year on his birthday and on Vidyadashmi day.

You have been known to perform for many Arangetrams. Tell us about your experience in playing for these live dance performances and some of the techniques required for playing for dance vs kutcheris?

I was very fortunate to be Krishnamurthy Sir’s student, which enabled me to learn and play for dance. He was well-known as a mridangist for Bharatanatyam, after his 14 years as a faculty member at Kalakshetra. The first lesson he told me in playing for dance is to listen to the vocalist and watch the dancer’s feet – “You are playing for the music and for the dance.” As I played, I learned. The skill-set differs, as you need to be accommodative when playing for dance. Before playing for arangetrams, I first played for dance programs with Temple of Fine Arts, Kuala Lumpur from 1983. Swamiji would call me over and I used to play for his satsangs. During my younger days, I also played regularly for Sai bhajans and Divine Life Society. [Ramanan is unique for his generation to be apt and skilled in both the playing for music kutcheris and for dance recitals like his teacher, Krishnamurthy sir.]

Over the decades, you have played for numerous Arangetrams (exceeding 500 to-date), worked with many dance schools. What has your experience been like?

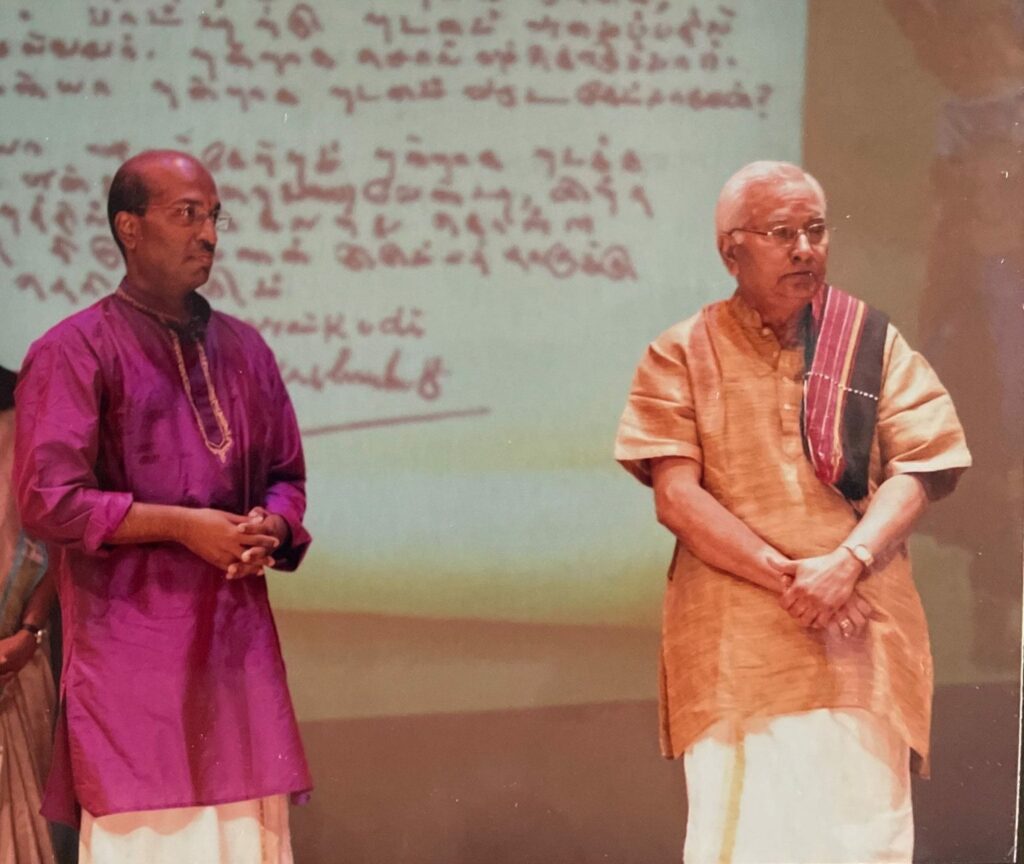

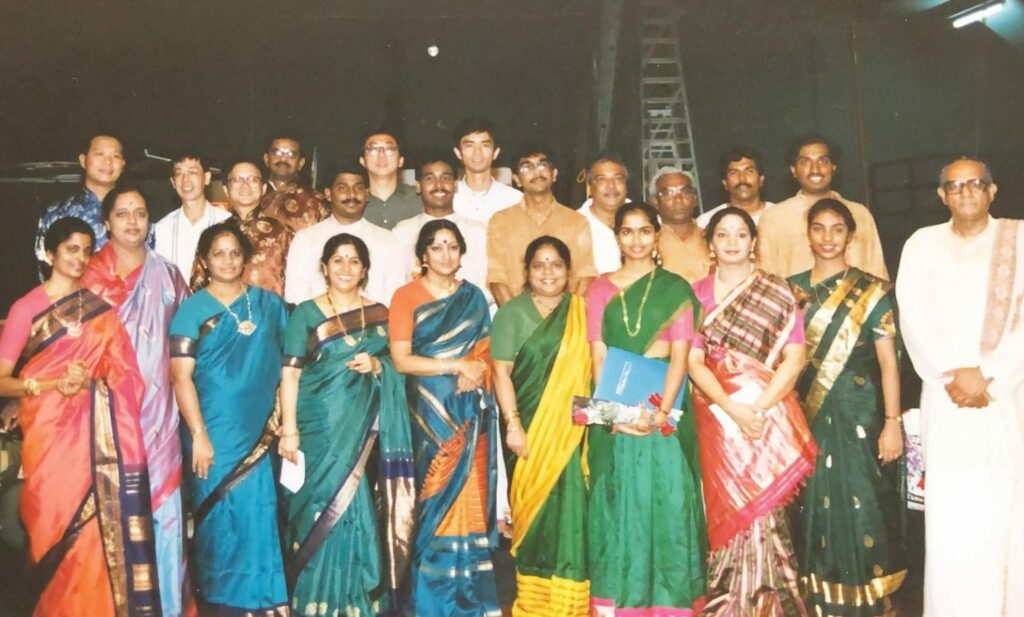

I would say that every experience calls for patience and a willingness to adjust and adopt. Working with a variety of styles, approaches, items, capabilities is part of trying to make the performance successful. You have to look and understand the dancer’s abilities without any preconceived notions. Along the way, the rehearsals are opportunities to fine tune and make corrections. Arangetrams are important. It’s a culmination of years of learning and is a significant juncture showcasing the commitment to the art form and brings to stage a milestone landmark. A milestone arangetram for me was playing for my daughter, Sukanya. Krishnamurthy Sir came as our chief guest and both Satyalingam and K P Bhaskar graced the occasion.

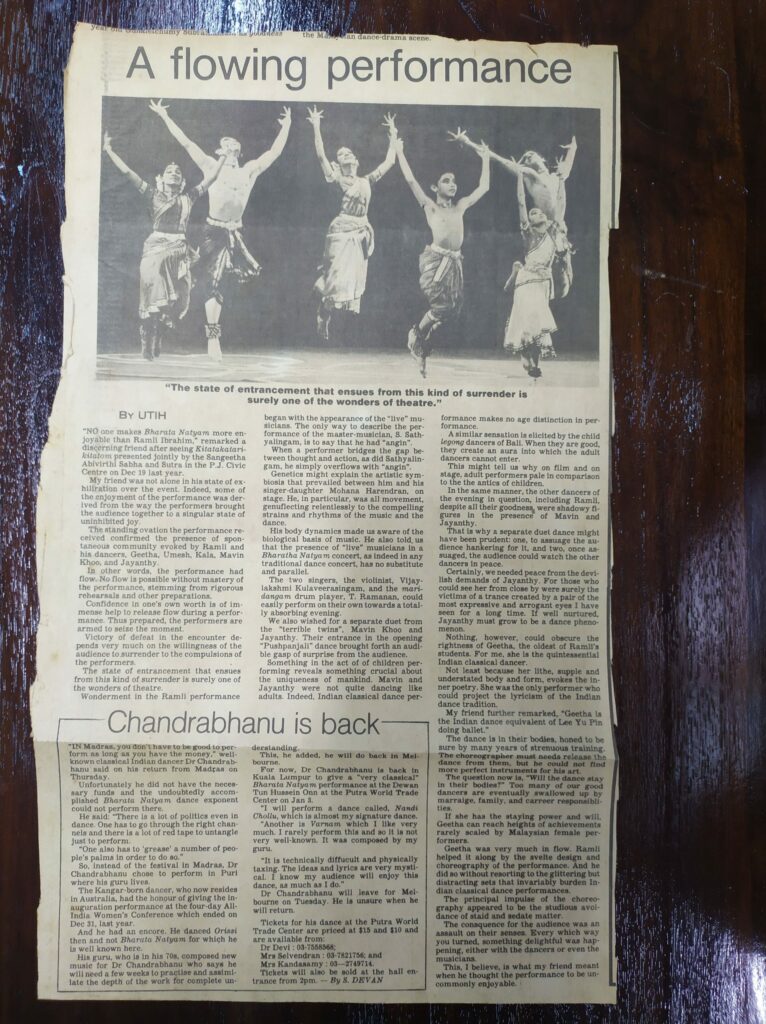

In recent years, I’ve noticed Arangetram choreographies have become more complicated and sometimes dancers struggle with this. Arangetram is a necessary milestone to cross and a reflection of the cumulative years of hard work and commitment to the art form, perhaps matching complexities with the dancer’s capabilities would further enhance the output in this day and age. Dancers should consider the arangetram as the first stage and should continue to learn and develop. I have travelled overseas to play for arangetrams – Malaysia, Indonesia, Australia and as far as the USA. There are differing standards, teams vary but the common aim is to create an enjoyable occasion for all. I have played for a number of dance programs with notable vocalists such as O S Arun, A S Murali, Muralidharan, Babu Parameswaran and Radha Badhri. I have also been a part of many dance productions over the decades. One of the first was with Neila Mami in 1988, “Mehame, Mehame.” featuring many Apsaras Arts alumni like Balakrishnan, Suganthi & Jeyanti Kesavan, Vijaya Nadeson and the People’s Association Orchestra.

I was part of SIOC (Singapore Indian Orchestra & Choir) for about 20 years. Working with conductor Lalitha Vaidyanathan, I recall we had T V Gopalakrishnan, L Vaidyanathan, Rajkumar Bharathi who came to mentor us, teaching us how to develop orchestral and choral repertoires. MS Viswanathan was a noted composer we learned from too. Ghatam V Suresh was one of the genius percussionists who taught us. All of these experiences were interesting and enlightening. In the 80s and 90s, we received a lot of press coverage for our performances when we collaborated with many notable musicians.

Share with us the first time you met the Satyalingams and your experiences with them in their lifetime.

I remember I first met them at their home at Sarkies Road. Initially Krishnamurthy Sir used to play for them, that’s how I was first introduced. I was very impressed with Mohana akka to begin with as she could both sing and do nattuvangam, a rare skill few have achieved. I started to work with them for their dance productions and Mama for his temple and television kutcheris. Mama was a no-nonsense person, highly disciplined and principled about decorum and punctuality. Mami was soft-spoken and accommodating. They had different working styles, creative arguments. They were both very kind and loving, offering support even during my wedding. They treated me like a son. I recall one of my early dance programs organised by Ramli Ibrahmin featuring a young Mavin Khoo where I performed with the Satyalingams in Kuala Lumpur. Over the decades, I have travelled with Mama and his daughters Mohana and Nandana (based in Canberra) for programs and arangetrams there. I have continued to work with them for their student’s arangetrams as recently as November 2019. I have also worked with Mami’s cousin, Ananthavali based in Sydney. I have pleasant memories of both of them, spending time at their home for rehearsals and many visiting artistes congregated there as well. From actress Shobana to Ravi Shankar, my memories are etched with these encounters associated with the Satyalingams. Mama was strict yet lovable. He was charming and had an enigmatic personality. One major and memorable production for the Singapore Arts Festival in 1992 was “Ritu Mahatmiyam” involving many dance schools and the amazing music of Padma Subramanyam, the first of its kind. My wedding was in the middle of this production and everyone involved attended, halting rehearsals for a day!

As a regular concert performer, can you share your experience performing in different countries?

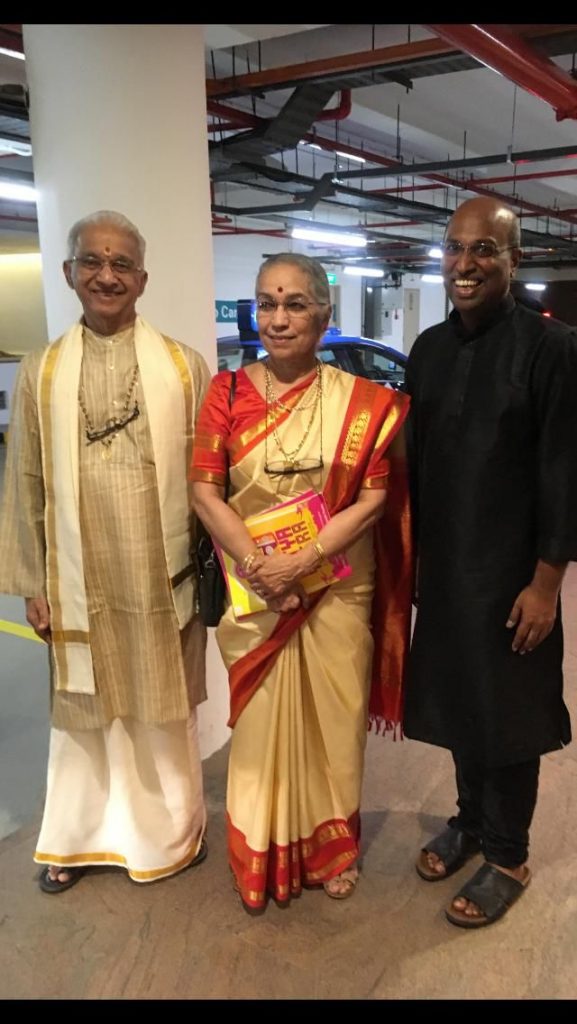

Generally speaking, in Malaysia, audiences tend to be able to endure long-drawn concerts that exceed three hours. People won’t leave till the very end. One of my enduring friendships is with Aravinth, a fellow musician I first met at Temple of Fine Arts, KL in the late 80s when Swamiji would call us over for recordings. We performed regularly – myself on mridangam, Aravinth on veena and Ghanavinoden on flute at various platforms. In those days, I was busy with back-to-back performances, sometimes up to a 100 in a year. Practically every day, I’m at rehearsals, going for weeks on 3-4 hours of sleep! In those days, travelling to KL was on an overnight bus. We were part-time musicians maintaining a day job in Singapore. Over time, I worked with Aravinth in Temple of Fine Arts, Singapore and thereafter when he was with Bhaskar’s Academy and then the Satyalingams in Apsaras Arts performing in kutcheris, arangetrams and then productions. Even though it was tiring, we had a lot of fun together. Aravinth and I have travelled on many overseas tours of Apsaras Arts productions till today.

Playing for Bharatanatyam in India, is a completely different experience. The way the audience interacts and gives feedback changes from venue to venue. The vibrations from the audience as well as other aspects such as sound, lighting etc have a clear impact on the performers on stage. My encounter with these diverse range of factors have increased my awareness of its influence on performances.

What does Apsaras Arts mean to you as an organisation in Singapore. How do you place it within the traditional arts fraternity in Singapore?

For me, the out-of-the-box moment came with the concept behind “Nirmanika,” the production by Aravinth. This was the game changer for Apsaras Arts. To be able to conceive and think in this way was truly amazing. Even Angkor and the many productions he has created have really pushed boundaries in dance productions. [A restaging of Nirmanika: Reimagined celebrating its 10th anniversary is expected to be staged at Victoria Theatre in late February 2022]. Aravinth has creative wisdom and has brought about a higher standard of production quality both in terms of Bharatanatyam choreography, musical score and soundscape bringing a unique visual and sensorial experience to the audience. Cutting-edge technology is seen in stagecraft as well. For me, Apsaras Arts is constantly evolving and rejuvenates itself by keeping with current trends. It has been making important waves within the industry, helping to shape and develop it as well. Now, a worldwide audience and recognition has also been attained.

What are your observations about the traditional Indian arts scene in Singapore?

Today we are seeing many more schools and teachers offering classes and more people are learning. There is a lot of variety. I’m happy to see more children enrolled which will go a long way in preserving the arts. It is also encouraging to see an enhancement of learning and development opportunities for students to deepen their interest in the pursuit of the arts.

How do you see the future of mridangam learning and performing in Singapore? Why should one learn this instrument?

Besides its musical quality, the mridangam has spiritual resonance. I continue to be captivated by the instrument. The sound it creates, I can listen to it and still be inspired. It has a timeless character. Maintaining a mridangam is challenging but every time I listen to artistes like Palghat Raghu, I’m in a perpetual state of joy. Many are learning the instrument but should also be mindful not to compromise on practice rigour due to other commitments. Exposure to all kinds of music is important when learning. Listening to concerts, attending performances regularly are part of knowledge appreciation and understanding nuances. To apply it in the context of classical music and dance, parents play an important role to help their children’s musical development. Based on my observation, I see many mridangists more willing to play for kutcheris and fusion concerts rather than for Bharatanatyam performances. Perhaps this could be attributed to the long rehearsal hours that are required. This may be a cause of concern for the future. I’ve been teaching mridangam at Apsaras Arts for the past year and have been involved in the technical project creation of Avai launched in July 2021. It’s about time that Apsaras Arts had its own creative lab and space to explore small-scale productions and showcases. I look forward to being a part of them and watching budding talents develop themselves here.