The Dance of Life

When acclaimed Bharatanatyam dancer-choreographer decides to share her journey in re-imagining the solo, you know you are in for some precious lines you want to, as a dancer, remember, and keep re-visiting for life. Excerpts from a lecture Gratitude “When I thought about the title, Re-imagining the solo Bharatnatyam dance performance, I wanted to pause and firstly acknowledge with gratitude the hereditary families and what they have done for us and for the dance. They are really the custodians of this art form; they treasured it, found their dignity through it and brought it to us despite setbacks and despite being marginalised.” The Rigour of Dance “Dance is a rather rigorous, unforgiving tradition. Practising it, day after day, is not easy; it’s a struggle, in fact but struggle is life.” Starting Solo “When I began dancing as a soloist, I must say had to approach it with caution, and with a sense of friendship but slowly I found myself going towards it. After around 15 years or so of training, I slowly started finding that classical dance was slowly starting to becoming a language. It took me a while to arrive at this clarity, so to speak but when I recognise that it was in fact, a vast, expansive language, it opened up for me so many vistas, possibilities allowing me to re-imagine it and turn to my inner voice and ask myself some important questions. Dance is not merely about the aesthetics, the symmetry, the poetry, the metaphor… And then of course the incredible possibility of the adavus itself. Of course, all of this needs to be all this need to be kept in mind but finally it was also about finding a sense of inner alignment. And the more I look within, I began to experience dance as a moment of living vastness.” The importance of intention “Why should dancers ask themselves this question of intention. What is intention in dance. what is my intention? It is honestly the very being. When we change the intention, the awareness, the dance itself changes. The dancing body has many levels — physical, emotional and spiritual and it is all staggering but it’s crucial to locate these different realities within your being. Once that recognition happens and if and when these three strands come together — intertwine, so to speak — the performative becomes the artistic. And what unfolds is, magic! Practice, practice, practice! “Dance is so much about repetition and yet how can we, as dancers, individuals, keep afresh, refresh ourselves, every time we come to practice and perform in a way that we feel it for the first time. I think that quest has propelled me to ensure that despite the demands the dance makes on you, you have to always surrender to it because in surrender, there is strength.” The Individual Feminine: “Khajuraho” “I started re-imagining, Sringaram that is so prevalent (pradhanam) in the Bharatanatyam repertoire, we think of the woman, waiting for her beloved. At some point, early on when I began asking myself some pertinent questions about my dance, I remember seeing a miniature painting of a woman who was bold, passionate, stylised and sensuous. The more I looked at her, the more I was convinced of the need to celebrate her individual feminine desire that was all expansive and universalised rather than a mere coy decoration that is a stereotype of sorts. The Divine Feminine: “Shakti Shaktimaan” “I was initially very cautious to interpret the narrative of the Mahishasura Mardhini; I felt I didn’t have the language to entrust myself to depict her. But some life experiences prompted me to envision her energy and I thought of a sculpture I’d seen at Mamallapuram of the Mahishasura Mardhini and I felt a connection and I felt I was ready to move towards the interpretation. When we look at a sculpture, there’s a lot we can learn about how its maker interpreted it and also the body language of the sculpture itself can tell is a story. Because after all, dance is about observation, people, experiences. Dance doesn’t happen only in the dance class; it happens when you live life and continue to look around.” The Ordinary, Extraordinary Woman: “Thimmakka” “When I read a story of Thijmmakka on a flight, I felt the urgent need to tell the world her story. She was a woman of great spirit and her story is a story of how she changed the course of her life, turning grief into affirmation. I felt I had to dance her story. And let people celebrate the extraordinariness of this human being. The arts is meant to make us empathetic. Outer to Inner: “Laya” “My journey with Laya began with my intention to journey in abstract dance and to work with movement vocabulary to suggest a person who travels from the outer to the inner.” This session was hosted by Vidhya Nair, Apsaras Arts. Tomorrow, September 7, tune in at 4.30 pm — 5.30 pm (IST) for Dr S.Sowmya’s lecture on the Veena Dhanammal’s School of Padams 5.30 pm — 6.30 pm (IST) Rama Vaidyanathan — Tumris in Bharatanatyam

The Aha Moment!

In the first-ever lecture demonstration exclusively focussed on music, Veena Dhanammal’s School (of Padams), the prolific and brilliant musician, Sangeetha Kalanidhi Vidushi Dr S Sowya took the participants of the Dance India Asia Pacific on an hour-long tour of the many qualities that not merely distinguish the Veena Dhanammal bani but also the many aspects that make it sparkle and shine. Befittingly, this session was hosted by young talented and eclectic musician, Sushma Somasekharan. As a musician who had the good fortune of learning from T Muktha (Mukthama) herself, Dr Sowmya focussed her lecture in letting participants appreciate the very “ethereal, addictive almost” quality of this bani which is regarded as a yardstick in terms of its adherence to traditional values and profundity of musical expression. Touching upon three essential aspects — the beauty of subtleties, the importance of brevity and the adherence to tradition — Dr Sowmya extrapolated each of her points with examples from her own repertoire and recalled anecdotes from her own experience of learning from Mukthamma. Speaking about subtleties, Dr Sowmya talked about the importance of listening keenly to appreciate the many layers and nuances this bani is made of. “You have to learn to be sensitive to the music while listening to it; you have to,” she said, referring to the bani, “be an observer and practice listening in between the notes.” Equally attractive is the quality of brevity in the music. “Even the alapana of a ragam like a Thodi or Shankarabharanam, for instance,” she said, “in this school is taut and power-packed. It is the concise nature of the presentation that makes this music so exciting and energetic at the same time.” The brevity is not merely restricted to the very structure and constriction of the raga aalapana or the rendering of a krithi but also in the very spacing of the phrases and in a manner that in singing a phrase, the bani seeks to capture in a moment, the essential quality of the ragam itself. Dr Sowmya also used the metaphor of contrasts and spoke about how just the way we need darkness to appreciate light, the school beautifully emphasised the simplicity of plain notes in a way that people appreciated the ghamakas. In terms of adherence to tradition, Dr Sowmya used the Tamil word, Paadam (the compositions) to highlight the core of this bani that has in a sense, retained and remained true to its legacy and has carefully passed on this music from one generation to another in the hope that even though change is inevitable, it continues to be subtle and seamless. Speaking of the Padams, that are integral to the repertoire of Bharatanatyam, the Veena Dhanammal school has become also synonymous with Padams. But the beauty of these padams, she said, are more than the mere fact that they are so “raga-laden, and full of curves and movements, subtleties and nuances but that it manages to appeal not just to those who appreciate the music but also to the common man who continue to find in it, Aha moments, aplenty! After all, it’s the Aha moments that we continue to seek, right? In the arts, and in life! Up next Thumris in Bharatanatyam by Rama Vaidyanathan

The Dance of Passion, and vice versa!

Who better than acclaimed dancer, Rama Vaidyanathan, who in her own words, called herself a perfect amalgam, a “hybrid of the North and South Indian culture of India” to capture and bring alive the essence of the thumri and her own journey with incorporating it into the vocabulary of Bharatanatyam. In a pre-recorded session where Rama Vaidyanathan shared stage with a bunch of eminent musicians — Dr Nabanita Chowdary on vocals, Mithilesh Kr Jha on tabla and Sumit Mishra on harmonium — the lecture demonstration literally transported the viewer to the court of Wajid Ali Shah of Lucknow, in whose period, somewhere in the 19th century, the thumri that literally is born out of the Hindi word, “thumakna” (meaning to move) found its genesis. It’s perhaps got to do with the curation mastery of Aravinth Kumaraswamy that Rama Vaidyanathan’s session was soon after Dr S Sowmya’s session on the Padams of the Veena Dhanammal bani. Rama Vaidyanathan drew interesting parallels between these two traditions reinforcing how they grew and became popular almost at the same time in two different cultures but were performed inherently by the courtesans who belonged to the hereditary families. “If you look at the Padam and the Thumri, you will notice they are both rich in poetic content with an accent on lyrics both the singer and the dancer attempt to portray subtle and varied shades of the meaning of the poetry which is usually focussed on the intimate, passionate moments with the lover, of a god who becomes a lover and of pining for a beloved who is sometimes the Lord; the speed or the pace is usually slow except the thumri picks up pace towards the end with the tabla. For me, these similarities across two cultures is a huge unifying factor in the history of Indian classical dance.” “As a dancer,” Rama said, “who studied Bharatnatyam in Delhi but grew up with access and exposure to Kathak and Hindustani music, I continue to be fascinated by the versatility of the Bharatanatyam idiom and its ability to transcend boundaries of language, musical genres, and cultures to come alive and create powerful pieces of poetry.” To demonstrate this idea and to allow us understand and appreciate how the thumri weaves into the fabric of Bharatanatyam, and so seamlessly, Rama Vaidyanathan demonstrated two beautiful thumris. Here’s an excerpt from a thumri is raag Pilu composed by the outstanding Bade Ghulam Ali Khan sahab of the Patiala gharana. The central motif here is that of laughter; as a friendly fight between Krishna’s friends and Radha’s friends, the thumri in Rama’s world sparkled with a joyous personality. As a stark contrast to that, in raag Shivaranjani, the second thumri, Ro Ro Nain Gavaye, brought to fore a heroine who has been scorned by her lover who doesn’t show up as promised; forcing her to pine and grieve even as she burns ragingly in passion, wondering about a youth going wasted — Umariya beeti jaaye. For a Bharatanatyam dancer, who is trained, honed and groomed to dance the padam, being able to portray the vipralabdha nayika (one deceived by her lover) isn’t new. But to understand it in the context of another context and culture, and dance in a way that the beauty of the language, the poetry and a musician from another genre, feel truly justified to find expression in a dance form that is unfamiliar with them all, is the genius of an artiste who owns her instrument, is multi-cultural and above all, one who has the unique ability to find similarities in differences, and vice versa and celebrate them all in her dance. A dance of freedom, of sensuality, of unbridled emotions, of passion, of life! This session was hosted by Seema of Apsaras Arts! Up next tomorrow 8 September — 4.30 pm — 5.30 pm : Chitrasena Dance Company — Kandyan Dance 8 September — 5.30 pm — 6.30 pm : Dr Srilatha Vinod and Anjana Anand — Silapathikaram — Dancer’s delight

Soul of the Soil

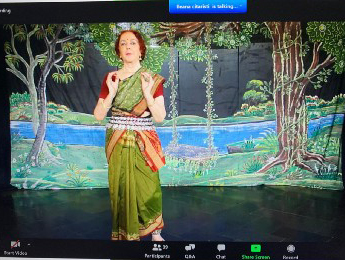

For the first time ever, in the history of Apsaras Arts’ Dance India Asia Pacific, participants were privy to a session exclusively dedicated to the history, practice and performance of Kandyan Dance by the Chitrasena Dance Company. Introducing the session, DIAP’s Curator, Aravinth Kumaraswamy said that it was a matter of great pride for the dance that belongs to the country he hails from — Sri Lanka — finds a platform on a global stage and the possibility of participants to appreciate the beauty and nuances of this brilliant dance form. Helmed by Heshma Wignaraja, Artistic Director of the Chitrasen dance company and its resident choreographer, whose grandfather was the legendary Chitrasen, founder of the dance company, and whose grandmother, Vajira, who began her journey as Chitrasen’s pupil, his partner on stage and off it thereafter and went on to become the prima ballerina of dance in Sri Lanka. Breaking the lec-dem into two parts, Heshma first touched upon the history of Kandyan dance referring to how it began as a ritual of sorts nearly 2500 years and originally had a mythical quality associated with it. Over time, in villages, the repository of the dance grew in the tradition of oral history and Kandyan dance evolved into becoming a dance ritual of sorts. In the early 30 and 40s, as society became organised, the dance found its way to modern stage. Chitrasena’s contribution, as Heshma pointed out was to distill the dance form from the rituals and infuse in them a sense of theatre in a manner that it became accessible to contemporary audiences. “Honestly, the genius of Chitrasena is that he didn’t seek to transform traditional dance forms,” she said, “In his world, new was an extension of the old.” The Chitrasena Dance Company was also instrumental in breaking barriers of caste, and gender barriers on stage. A pure, abstract dance form, without a linear narrative, Kandyan dance, was originally only performed by males and it’s ironical that today, there are more women who practice this form. The partner of a dancer in this dance form is undoubtedly the drums. Likening to the idea of a marriage, where one partner is incomplete without the other, Heshma spoke about how for a dancer to really understand her dance, it is imperative for her/him to understand the body of the drum and therefore translate that in movement. The second half of the demonstration was focussed on allowing participants appreciate not merely the many parts that comprise the language and vocabulary of this dance but also the process that goes into training dancers into being performers, on stage. Starting from the stance, the five central positions of the arms and the feet, the patterns it draws in space, the sentence structures, the way paragraphs find expression, the beauty and the strength of jumps, the recorded demonstration by Thaji Dias, Principal Dancer of the Chitrasena Dance Company gave audiences a crystal-clear sense of the language of this form. Demonstrating jumps in Kandyan dance Another excerpt from the demonstration by Thaji Dias Needless to say, to appreciate nuances, one has to dig further. But if the framework in itself is as powerful as what we saw, one can only well imagine how poignant and magnificent its soul would be! Up next Silapadikaram- Dancer’s Delight by Dr Srilatha Vinod & Anjana Anand

Stream of Consciousness: Dance of Human Conscience

What makes the Silapathikaram, the epic Tamil text a dancer’s delight? Why do dancers keep returning, time and again, to engage, and immerse themselves in this text to find new meanings and metaphors in it and translate those nuances in their dance? This session was conduced by the sensitive and talented dancer, Mohanapriyan Thavarajah, Principal Dancer of the Apsaras Arts. In a two-part lecture handled by Anjana Anand and Dr Srilatha Vinod, this text, yet again, came alive in all its beauty and glory. “There’s a storehouse of information in this text from every perspective,” said Anjana Anand, referring to her own love for the Silapathikaram, both from the point of a view as a dancer and a researcher, “As one of the greatest Tamil epics, and as a rasika of literature, first and foremost, one can find in it, an array of emotions — love, romance, heroism, revenge, dharma; it’s a true story of human struggle and also a powerful epic to document the three kingdoms of the Tamil country — Cholas, Pandyas and Cheras.” Anjana said she was only exposed as a dancer to Sanskrit literature but deep diving into the Silapathikaram allowed her the possibility to understand not merely the text and language but also a piece of Tamil’s cultural history. For the demonstration, Anjana chose to depict eight verses from the Kaanal Vari, the 7th canto in the first book. In it, you hear both the voice of Kovalan and Madhavi. This canto is interesting also because it’s a turning point of sorts in the text, when the “seeds of distrust shown on Kovalan’s heart have become like wheels strangulating their love”. Demonstrating five verses from this section, set to different ragams and capturing the many rasas each verse is layered with, Anjana’s demonstration also highlighted key aspects that go into a dancer determining to choose text to adapt it to her dance. “Is all poetry adaptable for stage? if so, how do we go about choosing it? she said and shed light on three crucial aspects amongst them a) Does the poetry have an inherent rhythm which makes it easier for a musician to set it to music? b) Imagery in the text; does it have an inherently visual quality to it for a dancer to play around with it? c) Dhwani or resonance; does the poetry allow the dancer to have multiple thoughts; is there something in the poetry that remains unsaid? For honestly, if there’s not, where would the dancer really be? Dr Srilatha Vinod, who has engaged time and again with the Silapathikaram chose to shared three poignant and powerful excerpts from her production on the Silapathikaram that premiered way back in 2004. Srilatha’s choice of the excerpts not only brought to fore the crucial turning points that make this text so classic and timeless at the same time but also was a true ode to the potential of dance to be able to create visual poetry on a bare stage with nothing but lyrics and music for company. It is the mastery of an artiste to identify — in the half a hour allocated to her — verses from a masterpiece that allow audiences, familiar and unfamiliar with the text, to get a glimpse of the potential and possibilities of the epic and of the dance to keep engaging with it. Befittingly, the first section paid obeisance to the sun and the moon and Srilatha chose the final excerpt also to be the sequence where Kannagi turns to the sun and the forces of nature to seek justice when she hears of the treacherous treatment meted out to her husband, Kovalan. The middle section we watched was the stunning dream sequence where Kannagi has a premonition of a tragedy that is round the corner, waiting to befall. Srilatha’s performance that premiered at the Koothambalam in the Kalakshetra and where she worked closely with an artiste called Unnikrishnan, also trained in the Kalakshetra to create this work, is a timeless depiction of a text that has withstood the test of time and continues to inspire and invigorate dancers. But like Srilatha rightly said, “The epic demands deliberate introspection of characters and of the storyline, else it is a very tall mountain to climb!” Truly so! But a dancer’s delight, nonetheless Up next 9 September — 4.30 pm — 5.30 pm : Dr Ileana Citaristi — Sancharis in Odissi 9 September — 5.30 pm — 6.30 pm : Aditi Mangaldas — Re-Imagining dance during lockdown (IST)

Between the lines…

On Day 5 of the Dance India Asia Pacific 2020, Padmashri Dr Ileana Citaristi took participants on a journey of sancharis in the world of Odissi. Drawing from her own rich experience in traditional and experimental theatre from her place of birth, Italy, followed by her extensive training and mentoring in Odissi by the legendary Guru Padma Vibhushan Kelucharan Mohapatra and Chhau Guru Sri Hari Nayak, Ileana brings to the stage shed light through a series of excerpts the concept of sancharis in the context of the dance she literally owns — Odissi. This session was hosted by Soumee Dee, an Odissi dancer and teacher at Apsaras Arts. Explaining the concept of the sanchari bhava, Ileana allowed participants to deep dive into the process of how a choreography with a central abhinaya and emotion lends itself to the possibility of “amplifications and auxiliaries that support and complement the main subject or the sthayi brava that the composition is laden with”. Dance, after all, is about reading not a poem as it is, but reading in between the many lines that it’s made up of and using her/his imagination, and creativity to layer the narrative with expressions and subtexts that are subservient to the sthayi brava but accentuate it, nonetheless. Her presentation comprised three excerpts from legendary Odissi exponent, Guru Kelucharana Mohapatra’s choreographies. The first excerpt was from the Ashtapdi, Yahi Madhava and brought to light a Radha who waits patiently and passionately for Krishna to arrive; she is adorned with garlands, the bed is full of flowers and studded with decorations, she waits for Krishna to arrive but when he does the morning light has almost arrived and it’s evident that he has spent the night with another woman. How does one therefore expand this narrative, the conversations, spoken and unspoken between the two, in a way that the pain Radha’s pain is enforced in a way that the dance becomes a visual allegory. Dr Ileana also spoke about the principle of inclusion and expansion. While working on sancharis, it is important for a dancer to not only understand the context of the narrative well but also to think deliberately upon how much to include and what really to expand upon. Her second excerpt was from the Ashtapadi, Sakhi Re, where Radha tells her sakhi to go and fetch Krishna as she is full of desire. And in a typical way that friends converse and like to share details of their many adventures, big and small, Dr Ileana used sancharis sensitively to create for the audience an atmosphere of that secretive-ness and suspense that makes her little exploits with Krishna so fun and exciting. “One has to look carefully within the poem to understand what the poet is trying to actually elaborate and go beyond the literal translation of the meaning of the poem.” After all, dance is all about the possibilities and in the world of a genius like Dr Ileana Citaristi, those possibilities become endless, and timeless at the same time. Up next Re-imagining Dance during the lockdown by Aditi Mangaldas

Dance of/in the now!

In a powerful and particularly relevant session titled, Re-imagining Dance during the Lockdown, acclaimed Kathak and contemporary dancer-choreographer, Aditi Mangaldas took participants of the Dance India Asia Pacific 2020 on a crystal clear journey into the creative thoughts, instincts and impulses that dictated and determined her artistic course over the last six months.“True art has to breathe the life of today,” Aditi said, referring to the title of this session and how she felt it was crucial for her not to remain in the past but adapt and use her art to reflect the narrative of the now. “I have been in two apartments, away from the earth but when I look out of my window, I see the ocean and the sky changing colours. I have been fortunate in the recent past to go to the countryside, smell the grass and feel life vibrating. I had to, in the last six months, keep the dance alive in my body, mind and heart.” Aditi allowed us to understand her process with re-imagining her own dance through the lens of six central ideas/words — Contemplation, Introspection, Compassion, Rejuvenation, Conception and Celebration. What was interesting about her entire journey was the honesty with which she envisaged the art in the current context. “I had to be conscious of my new reality,” said Aditi, “I felt it was not right for me to imagine Navarasa from an earlier production the way I’d imagined it before; so what you see in the short films re-interpret navarasa through various constrictions — bars, grills in windows, bubble wraps, tiny balconies, etc.” Central to Aditi’s talk was the importance of allowing your dance to become a window to the larger world, and not merely those who have typically followed your dance trajectory, so to speak. Elaborating on the idea of Contemplation, Aditi spoke about how a stage creates a certain physical distance between the artiste and the audience but somehow the lockdown became for her, a moment to reveal, share her vulnerabilities, anxieties and every day, in the early stages of the lockdown, she began sharing her dance within the confines of her home. “It was amazing how these videos travelled through the mountains and oceans and I had heart-warming responses from corners of the globe and even though they were saying thank you to me, I felt like I was saying thank you to them for reaching out to me within the space of my four walls .” Aditi’s re-imagination was also enriched by her own introspection and consciousness of not only her reality and sense of privilege but also recognising it in a manner that is inclusive, and one that moves forward. Born out of these ideas were a series of short films that were inspired by productions in the past and fused interestingly and innovatively with imagery and expressions current to the life of an artiste in the midst of a pandemic. Amongst the many projects and ideas that were born out of this period of contemplation, introspection, conception, rejuvenation and the need to celebrate the art within us, Aditi created Amorphous — The Zero Moment, a coming together of the original work Zero Moment choreographed by her way back in 2006 coupled with her creative impulse in the midst of a confinement where the concept of time seems warped. “It feels as though I am suddenly thrown into the river along with the rest of humanity and most strangely that the river has changed its course, from the ocean to the source. And this was the genesis of Amorphous — The Zero Moment.” Equally important was the notion of compassion that Aditi emphasised upon referring to how she collaborated with Raw Mango and ThemWork Arts to reach out to the thousands of artistic families that have nearly lost their livelihoods. “I connected with my dance company, and together, we decided to look at our past production, Within which was an interplay between brutality and humanity and using footage and music and the central concept of Within, we made six short films that were an interplay of freedom and confinement, lockdown and expansion.” The beauty of Aditi’s talk was that it was invigorating for a creative person to not merely appreciate the mind of an intelligent artiste like Aditi but also find within it, inspirations aplenty to re-look their own dance, through the lens of their own realities that pulses with life as we know now. Aditi’s most powerful statement was: “My dance is bursting through my bones but stopping at my skin. But that is my reality and yet there are myriad ways to conceive art through these very difficult times.” This session was moderated by Kathak dancer, Shivangi Dake of Apsaras Arts. Up next Light Design for Bharatanatyam by Gyan Dev Singh and Appreciation of Music and Poetry for Dance by Sujatha Vijayaraghavan, tomorrow September 10, 4.30 and 5.30pm (IST)

In the light of…

“In the right light, at the right time, everything is extraordinary,” said Aaron Rose. Listening to Gyandev Singh’s hour-long lecture on his exploration and experience of engaging with Bharatanatyam productions and lighting them, for the Dance India Asia Pacific was the opportunity to appreciate how lighting becomes a “co-creator of sorts with the dancer on stage”. “Lighting has the amazing ability to augment and hold space for the dancer and allow her/him to create and express herself/himself in a way that the entire viewing experience is enhanced.” Growing up in Chandigarh, Gyandev began by admitting that he didn’t grow up watching Bharatanatyam. “Perhaps my first exposure to Bharatanatyam that I remember vividly was a performance that I watched of Leela Samson,” he said, “I remember my parents took me for the performance and I still recall being absolutely mesmerised by what I saw. I loved how Leela Akka imagined so many objects and characters and I was completely taken in by how she held the audience’s attention there, all alone on stage with only lighting on her face, and create these beautiful images allowing us peek into her imagination.”A graduate of the National School of Drama (NSD), Gyandev’s tryst with the world of Bharatanatyam was piqued by his own curiosity of the idea of abstraction of the very nature of Bharatanatyam itself. “My constant pursuit has been to see how I can create design contexts wherein the lighting doesn’t merely illuminate the dancer/s but also is able to create a standalone narrative of its own on stage. I like the whole idea of using the stage floor to create a pattern on stage. I also continue to be fascinated by the geometry of the bodies, the lines they can create and I’m always trying to see how I can use my lighting to create a third eye.” Gynadev allowed his audiences insights into his journey and pursuit in the world of lighting through a series of examples from productions he has been a part of! Anjaneyam: Hanuman’s Ramayana by Apsaras Arts Hailed a visual treat, Gyandev talked about how he gleaned concepts from musicals to create for this mammoth productions a sonography. “I also conceptualised the idea of using projection mapping to create scenes and sceneries that looked like magical, painted backdrops,” he said. Disha: Spanda What happens when geometry and architecture decide to have a conversation with each other? Gyandev referred to Spanda’s Disha, a production where he used lighting to have a voice of its own, lighting dancers but also using the stage floor to weave interesting patterns on stage and for the audience to understand the interplay of lighting itself. “I’m also very intrigued by the idea of using lighting breaking up the body into parts and to see how each of these parts respond to lighting.” Gyandev also talked about his experiences with Thari by Malavika Sarukkai and spoke about how Malavika Sarukkai involved and included him right from the beginning of the production. “That way you understand it, in-depth from the start and start thinking about it collaboratively,” said Gyandev. He also shared excerpts from Mara by Mythili Prakash, Agathi by Apsaras Arts and The Tiger and the Bull by Ananda Shankar Jayanth. In Agathi for instance, he said Gynadev talked of how the lighting in itself became a sutradhar of sorts directing the viewer’s eye to the story. He shared a powerful scene — the boat sequence — where the lighting itself creates a pattern of a boat on stage. Here’s an excerpt: Equally powerful was a scene Gyandev shared from Parama Padam by Mohanapriyan Thavarajah of Apsaras Arts to demonstrate how “light and dance can play with each other”. Followed by an interesting Q & A, this session was moderated by Vidhya Nair of Apsaras Arts! Up next Appreciation of Music and Poetry for Dance by Sujatha Vijayaraghavan

Of words, and beyond

In yet another curation masterstroke by Aravinth Kumaraswamy, Gyandev Singh’s session on lighting was befittingly followed by a session on the importance of appreciation of music and poetry for dance by the versatile and knowledgeable Sujatha Vijayaraghavan. In a beautiful hour-long lec-dem, Sujatha Vijayaraghavan shed light on how the dance blossoms when the dancer digs deep into the poetry and the music of the dance and also offered interesting insights on how to do it, breaking it into simple, practical ways that could help enhance a dancer’s relationship with both these aspects. This session was hosted by Kritika Rajagopalan of Apsaras Arts. “You see, dance is often described as drishya kavyam, which means visual poetry and not visual drama mind you,” she said, “It’s the poetic quality of this form of dance that appeals to the rasika through the subtleties and evocative nature that it creates through the abhinaya.” How does one therefore set off their own understanding of poetry? How does one begin to appreciate and engage with poetry? Should one only be reading poetry that pertains to dance? “Not at all,” Sujatha said, “In fact you should read any poem; if you are familiar with a vernacular language, preferably your mother tongue, then that would be the best. This is because every language brings with it its own tradition, culture, thoughts, context, et al.” An important tip she shared was to always when starting to engage with a poem to interpret in dance is to find its most authentic source. “Don’t look at the internet,” she said, “Look for the right source and once you do that, attempt to find its contextual meaning. Read around the word looking to see what context it attempts to emphasise; try to get to what the poet is actually trying to convey.” Once you establish context and comfort, she suggested you move towards contemplation. “Read not the word,” she said, “introspect and ruminate over the poem, the words, let it marinate within and create some vibes and then after a while go back and read it again,” Sujatha Vijayaraghavan also referred to finding the poetic core and talked of the legendary Subramanya Bharathi’s compositions — a poem titled Agni Kunjondru Kanden and talked of how it allows the dancer to find in it interpretation possibilities, aplenty. She also talked of a verse from the Thurukkural and alluded to the importance of finding in those two words, the core essence of what is being said. “We know the core as finding the sthayi brava but sometimes it goes a little beyond that,” she said, “Sometimes the core may be in a single word. Like a pada varnam by maestro, Lalgudi G Jayaraman — Innam en manam ariyAdavar pOla irundiDal nyAyamA yAdava mAdhavA. The core word here, is Pola (meaning something like in Tamil), which actually reflects the state of mind of the woman who is entreating Krishna. Once you figure out the core word, your body language is dictated by this awareness. In this case, you recognise she is very much in love with him; all she wants from him is comfort and reassurance.” Speaking of music, Sujatha Vijayaraghavan spoke about understanding the ragam, layam and the sahityam. Carnatic music, she said, is ragam-based music and to appreciate it you have to listen to it, and a lot. “You have to make it a preoccupation,” she said, “Ragams are like colours; they create emotions and are evocative.” Speaking of layam, she talked of Jathiswaramn and Thillana that is an interplay of swaras but lending with its variations in layam, possibilities aplenty in terms of dance. The most powerful was the concluding piece Sujatha presented. A Pudu Kavidai by Vairmathu that was performed by them way back in 1992. “Woven around the concept of trees, this poem has no metre so it’s a challenge to set it to music and yet it has a flow. The final lines in the poem talk of how every tree is a Bodhi tree, a tree of enlightenment.” Perhaps, the hidden meaning is that there’s something to learn from everyone and seeking and learning are the best ways to enlighten ourselves! Up next on September 12, Lalgudi Thillanas by Lalgudi GJR Krishnan and Lalgudi Vijayalakshmi 4.30 to 5.30pm (IST)

Dance of Music, Music of Dance

In the penultimate webinar of Dance India Asia Pacific 2020, Lalgudi G J R Krishnan and Lalgudi Vijayalakshmi presented an hour-long live session on Lalgudi’s Thillanas that reinforced not only the ingenuity of legendary maestro, Lalgudi G Jayaraman but also the classic and aimless quality of his compositions that continue to woo, and wow performers and audiences alike across the world. Carrying forward this tradition, the Lalgudi bani, the duo, musicians in their own right and with accolades and awards aplenty, brought to fore the quintessential aspects that add a quality of distinctiveness to the compositions of Lalgudi Jayaraman. “You know, my father was often asked why he composed more of Thillanas and Varnams,” said Vijayalakshmi, “And his response to it was that his inspiration is both the laya and the melodic aspects of music and both these compositional forms allow me ample scope to express these aspects and layer it with my own imagination.” On a lighter vein, Krishnan spoke about how to a listener a Lalgudi composition may sound like “jalapeño pepper dipped in chocolate” but honestly, he said, “performing any one of his compositions requites a great amount of skill and practice”. Originally a ritualistic composition, credit to give the Thillana a face-lift and pride of place goes entirely to Lalgudi G Jayaraman who created compositions that forced people to “sit up and take notice for the way he wove into it musicality, melody, rhythm, poetry, emotions and the raga bhava, and all so naturally. In his scheme of things, nothing was ever contrived,” Krishnan said. On this day, dancers continue to dance to the compositions of Lalgudi Jayaraman and the duo spoke about how he used the concept of space in music almost like a dancer — “like the way, a dancer uses space on stage, you can see the concept of space in his music,” Vijayalakshmi said speaking also about he uses phrases intelligently and also one that defined the very essence of the ragam itself. Flamboyant in its very form and appeal, Lalgudi’s Thillanas are true embodiments of the idea of the marriage of contrasts — strength and beauty, melody and mathematics, aesthetics and freedom and restraint. “I see in his compositions, a poet, a painter, a sculptor, an architect,” Vijayalakshmi said, “He knew the colour of the notes, he used phrases like a poet, approached the laya like a sculptor and an architect and built an aesthetic edifice using them all. Quoting an example, Krishnan spoke about the popular Thillana in ragam Mohanakalyani, and talked about how when he plays it, his father almost imagined it like a deer that ran up a mountain and stopped every now and then, to look back and assess its course before it began jumping and running up the mountain. Or the Madhuvanthi Thillana, it’s almost like leaves falling down with a gentle sway and when you place the notes, it’s like you can see the leaves falling.” As a constant seeker, innovation was at the core of his compositions. Just like a dancer creates sancharis, his music too, they said, danced and had sancharis of its own. “There is in his music, an invisible continuum of its own,” Krishnan said. Here’s a little excerpt on his concept of Sruthi Bedham The lec-dem was also packed with anecdotes aplenty. Vijayalakshmi spoke about a story where when she was in college, her friend, dancer Sujatha Srinivasan evinced interest to perform her father’s composition in Kaanada. “I knew this was one of the compositions that was a part of the 8 Thillanas for Dance of Sound and I also knew my father hadn’t penned the lyrics yet. But when I put forth the request to him on behalf of my friend and suggested he could use the flower and the moon in the poetry, I remember how he beautifully did that and in hindsight, every time I think or perform this Thillana, it’s impossible to think or believe that the lyrics came after the composition was already set. To be a genius, is to be inspired and no one better than Lalgudi G Jayaraman who lives his life in a state of “being inspired”. The amazing thing about him, the duo said, was that he was so generous and equally inspired by a child as he was by a well-know dancer. It is a state we all seek and perhaps humility, empathy and sensitivity are amongst lessons wee can learn to appreciate from geniuses that created and whose compositions we continue to dance to; some literally dance, some others, like us who don’t dance on stage, let it dance in our minds! Up next is a conversation between dancers, Priaydarsini Govind and Shobana at 8pm (SGT)