NAVADISHA 2016

An opportunity to network with the Indian Dance Fraternity from the Northern Hemisphere By Aravinth Kumarasamy For the past two decades and more, I have been attending the Natya Kala Conference in Chennai, and a few other such international dance conferences in India and Singapore, in addition to the many ASEAN conferences in Thailand, Indonesia, Canbodia and Vietnam. It was a different experience to attend an Indian dance conference organised by a diaspora community in a western city – Birmingham, UK. The UK hosted a high-profile summit dedicated to Asian dance in May 2016, as one of the largest gatherings of artists, organisations, pundits, policymakers, funders and fans of dance from around the world gathered under one roof for Navadisha 2016. Produced by New Dimensions Arts Management in partnership with Sampad, Navadisha 2016 (meaning ‘new directions’ in Sanskrit) posed crucial questions designed to stimulate, steer and secure the future of British Asian dance as part of the UK’s ever growing dance landscape. It also celebrated many of the breakthrough achievements and exciting developments in and around the sector during the fifteen years since Sampad’s seminal conference Navadisha 2000, which helped to blaze a trail for a new generation of dancers and practitioners, sparking pivotal insights and actions across a variety of fronts, from artistic to organisational and political to structural. Navadisha 2016 attracted a line-up of 65 speakers, presenters and panellists from 25 cities in 12 countries and more than 150 registered delegates. It was a rare and valuable opportunity for dance practitioners, teachers, students, academics, agencies, programmers, venues, promoters, investors and policymakers across the arts sector. The three day programme covered a range of topics – from artist development to international collaboration, and contemporary factors that were shaping South Asian dance creation and distribution. It also highlighted models of excellence and innovation, and explored new ways of working. I was invited as guest presenter at the conference and had the opportunity to share about the work we have done inspired by South East Asian narratives. Apsaras Arts had an exhibition booth which attracted many delegates to come over and learn more about the Bharatanatyam based ensemble productions of Apsaras Arts Dance Company, Singapore. It was a great opportunity to network and meet up with many dance personalities from UK, Europe and USA in Birmingham. Though many of the presentations were UK centric and being practitioner of Indian classical dance based in Asia (Singapore), it was interesting to learn the term “South Asian Dance” being widely used at the conference by most speakers. It was also an eye-opener to see some of the contemporary works being experimented by UK based Indian dancers. The key-note speakers Shobhana Jayasingh, Akram Khan and Mavin Khoo raised a few thought provoking questions. Please see following links to read these keynote speeches presented at the conference Shobhana Jayasingh and Akram Khan I would say it was one of the most memorable dance conferences I have attended and many follow up conversations and collaborations were created at this event for Apsaras Arts.

Interview with Radha Vijayan – Driven by passion and devotion, a celebrated musician reflects on his life’s journey

By Vidhya Nair VN: Tell us about your family background – family members & growing up years in India? RV: I was born and raised in Chennai. Around the time of my birth, my father was already a well-known celluloid-film hero – Madras Kandaswami Radhakrishnan, known professionally as M K Radha. His father, my paternal grandfather who was a lawyer, Kandasamy Mudaliar was an avid theatre-maker and had ambitions for my father to be a leading actor. In the 1930s, he was one of the earliest theatre directors to present Shakespeare plays in Tamil. It was my grandfather’s script for “Sathi Leelavathi” [based on S S Vasan’s (who founded Gemini Studios) novel of the same name, also based on an English novel] which became my father’s debut film in 1936. The story explores themes of temperance, social reform, Gandhian concept of selfless service and the plight of labourers. The film was a hit and my father became an overnight star and he remained so for the next twenty years resulting in him receiving the Padma Shri in 1973 and a colony in Teynampet, Chennai named “M K Radha Nagar” in his honour. Incidentally, my father’s debut film was also the debut of M G Ramachandran (MGR) who also went on to become a leading actor and politician recognised and highly regarded around the world. They belonged to the same theatre group – MGR, his brother, M G Chakrapani, my father so it was like a family. Many of the actors of that generation came to be known in my home as members of our own family – we called them Chittappa & Mama. MGR Chittappa, Shivaji Chittappa, NS Krishnan Mama, Thangavelu Mama, Balaiya Mama was how I would address them. A well-known film my father acted in was “Apoorva Sagodharargal”in 1949 where he played the double role of look-alike brothers produced at Gemini Studios in Tamil, Telegu and Hindi simultaneously which had Nagendra Rao as the villain and P Bhanumathi as the female lead, who also sang most of the songs. The two brothers my father played in the film were Vikramasimhan & Vijayasimhan. I was born during the making of this film, that’s how I came to be named Vijayan after this film character and professionally, I came to be known as Radha Vijayan. I was the youngest of 8 children and 1957 when my father had a heart-attack and it became difficult for him to continue acting. My late eldest brother, an engineer became the backbone of the family and helped raise us all. One of my sister’s married film actress, M S Santanalakshmi’s son, M D Seetaraman and another sister married E V Saroja’s brother, E V Rajan, film producer. Some of my siblings has passed and rest are based in Chennai. I myself married Usha, daughter of Karukurachi P Arunachalam – famed Nadaswaram [ acclaimed for the timeless classic “Singara Vellan” track, a breakthrough hit for S Janaki in the 1962 film “Konjum Salangai”]. I have only one daughter, Abhirami. and I have a grandson, Aryan who is now a 10th grader. VN: Tell us about your learning experiences with music in your younger days? RV: From a very young age, I had a great passion for music. As a child, when I would go with my father for his film shootings, the moment I saw the assembled orchestra, I would be seated with all the musicians, watching them intently. I was a self-taught guitarist, by listening I came to imbibe the melody and techniques. There was not much encouragement from my mother’s side because they were familiar with the film and music industry. If there was a recording, you had wages otherwise nothing. Guitar unlike today was not known widely in the 1960s when I was a youngster but Manikavinayagam, my cousin (son of Vazhuvoor Ramaiah Pillai – famed Nattuvanar and Bharatanatyam guru) had a very old hand-made guitar at home. I used to spend time after school at his home and he gave that guitar to me. I restituted that guitar – stringed it and practiced on it much to my mother’s unhappiness who was keen I focus on my academic studies. E V Saroja noted my playing and bought me my first electric guitar. I learned both Western & Carnatic tunes by listening. The lyrics didn’t matter and I practiced regularly. Then it came to a standstill as I didn’t have a teacher but many who heard me felt I had potential. It was a friend, Krishna who recommended me to Dhanraj Master who accepted me earnestly as knew my father who was the star of that film, Chandralekha (1948) where Dhanraj Master had performed for the soundtrack of the film, This was a historical period film, then the most expensive film of its time, distributed internationally and today considered an Indian classic. I was 12 when I started learning with him and at 13, I performed my first concert in school. He would get me to write out notations, taught theory and I also picked up skills in piano as well which aided my keyboard playing later. It was at this time I met my best friend, Sadanandan who became the lead guitarist for Iliyaraja. We used to practice for hours together, often the guitar pieces of S Philip, the leading guitarist in filmdom and I dreamed of meeting and playing with him. I was able to achieve this dream finally in the 1980s. I also completed my classical guitar studies from Trinity College of Music, London and Indian Classical music under Karnataka Vainika Gana Vidyalaya and my interests broadened to include rock, pop, blues, country, jazz and fusion music. As I was a gold medallist in my degree program, I was easily recruited by a leading petrochemical company, music became a part-time activity. In 1965, I got to perform guitar in my first recording for a theatrical film. VN: You began to work with Indian music directors from the 1960s onwards. Share with us

NRUTHYA KARANA: A salient feature of any theatrical presentation

By Naatyaachaarya V.P.Dhananjayan A lesser known treatise on Naatya is Nandikeswara’s BHARATAARNAVA. Another work Abhinaya Darpana is also attributed to Nandikeswwara – a practical theory text in vogue, taught and applied in today’s Bharatanaatyam . As you all probably know, the theoretical application of Nandikeswara’s Abhinayadarpana started with the establishment of Kalakshetra, where Naatya Saastra and Abinayadarpana became an integral part of curriculum . Now of course every school of Bharatanaatyam makes it a point to teach Abhinayadarpana to an extent , if not Naatya saastra. All serious students of Naatya, with professional interest pursue the study of all theoretical aspects of Naatya and several of them have done research and obtained Phd-Doctorate in Natya theory. Though knowingly or unknowingly Bharatanaatyam practitioners use certain appropriate Karanas for delineating Abhinaya or emotions. AS you all probably know Bharata’s Naatya sastra is the ultimate reference treatise for all performing art forms including stage dramas like Kalidasa’s Shakunthalam, and the later editions of texts are mainly based on the mother book, more or less an extension of the main text. In Naaryasastra the main thrust is on the 108 Karanas , with categorisation of Nritta karana (for dance in general) yuddha Karana ( combat postures & movements) and niyuddha Karana (acrobatics like in Kalarippayattu , Tai Chi, Karate etc)(NS SAYS : hasta pada samaayuktho Nruttasya karanam bhaveit — a combined movement of hands and feet is nruttakarana. “Nrutei yuddhai niyuddheicha tathaa gati parikrame. karanani prayoktavyam – Karanas are used in Nrutta, yuddha (war) and niyuddha (small combats) depiction in Naatya presentations. Coming to the Nrutyakarana or Abhinayakarana, which are more explicitly described in the Bharataarnava treatise let me throw little light on the subject. matter. Naatyasastra generally talks about the mandalas(postures) and movements for Abhinaya, but Nandikeswara in Bharataarnava expounds further with details for each and every gesture and emotions.Abhinaya means -carrying forward-that is, communicating the meaning of the poem or song consisting of meaningful words. Instead of simply emoting through the face — known as ‘uttamaangaabhinaya- combining certain postures ,positions and movements, accentuate the actual communicative aspects. For example, the movements of Fish, or bee or butterfly or river Or samudra etc could easily communicate the object even to a lay audience. In common parlance Bharatanaatyam artistes and their Rasikas believe or are made to believe that “abhinaya” is only through face and total ‘Angika’ (consisting of) – anga prathyanga , upaanga prayoga – usage of complete body language is not needed or essential for ‘bhaava prakatanam’. In the Sadir or Devadasi tradition they focused only on facial expressions and not incorporating the full Aangikaabhinaya or Naatyadharmi mode of communications or presentation. Following the Kathakali method and finding the roots from Treatise, Rukminidevi in Kalakshetra, in consultation with scholars, reintroduced the Nrutya karanas or Abhinava karanas while delineating or interpreting ‘padaarthaabhinaya(word meaning) and vaakyaarthaabhinaya (a spoken sentence). Bharataarnava prescribes Mandala staanas (positions) and Abhinaya karanas for each and every ‘hastha’ & mudra. A physical demonstration would make it more clear to the onlookers. It is apparent that we need to renegotiate structures in our personal and professional lives to make sense of a post-COVID-19 world. The challenge to transform demands holistic action from us – as people and as artistes and, in this article, I look at the world of dance in particular. All said and done Bharata being a visionary has envisaged evolutionary changes and creativity in the generations to come (Bhavishyatascha lokascha sarvakarmanusaadhakam) .Bharatarnava further suggests Abhinaya karanas for objects with no sentiments or emotions like ‘sthavara’ ( tree, mountain, river, ocean, ball ,vessel, cart etc) and ‘jangamas’ like all kinds of animals and objects with life. Naatya saastra elucidate“ Aakritya cheshtaya chinnai jatyaa vignaya vasthuta haSwayam vitarkya karthavyam hastaabhinayam budhaihi” Meaning: According to the form, behaviour, categories (animal or human or objects) intellectuals could create their own mudras and abhinaya karanas. Movements in rhythm of animals such as elephant, horse , monkey, tiger, lion, ball game, Birds, spiders, wolves , jellyfish, submarines , rockets etc can be effectively portrayed with the help of Nrutya karanas. We can also show cricket or any other games, Flying, Etc in naatya. So the saastra has given us liberty to create and expound according to necessity . As the saying goes, necessity is the mother of invention. So over the years creative artists have evolved new gestures, new karanas to suit the requirements of the changing time. Naatya Saastra or the science of dramatics consists of all aspects of aesthetic art forms including pure dance, expressional movements, Sangeetam or music, drama, architecture, sculptures, Yoga etc. So the word Naatya is a comprehensive term for all aspects of theatrical art forms. “Na tat silpam na tat janam, naasaa vidya na saakalaa, naasow yogo natat karma Naatyesmin ya na drishyatei” This verse from Bharata’s Naatya Saastrajustifies that “Naatya” is the most appropriate term to denote all our theatrical arts forms, classical dramas included. So naatya can be defined as a combination of Nrutta(pure dance movements in rhythm) , Nrutya ( nrutta and abhinaya combined) drama (story telling). Article by Naatyaachaarya V.P.Dhananjayan, Founder/President, Bharatakalanjali, Chennai.

Inauguration of AVAI at Apsaras Arts

On 10th July 2021, AVAI @ Apsaras Arts, a performance space for Indian Performing Arts in Singapore was inaugurated. When we scouted around for names for Apsaras Arts’ own performing venue – an idea that was born nearly five years ago and is finally finding fruition – we were keen for it to be a word that represented and celebrated the premise, intent, spirit and sanctity of the space. We were keen the word conveyed -in short – what it was meant to be but also was packed with meaning and has a sense of continuity. That’s how we located AVAI, a Tamil word that literally means congregation, gathering, coming together, assembly of scholars, poets, artists, thinkers, do-ers, and intellectuals, of people who shared similar interests, energies and are part of an experience, together. It is housed within the office of Apsaras Arts, at the Goodman Arts Centre, Singapore, our home-away-from-home for 11 years now. In its sanctum sanctorum – so to speak – that has been our studio, ideas and thoughts, ingenuity and imagination, energy and experience have birthed and been nurtured; dancers, musicians, scholars and poets from far and wide, from home, our home in India, and from foreign lands, have shared their arts, discussed their processes, found in it rigour and shared it with students and those waiting and willing to imbibe it all. Drawing its design inspiration from South East Asian elements and raising a toast to all things Indian in the world of the performing arts, AVAI is also an extension of the Apsaras personality. Like its name – short but full of character and meaning – AVAI is all things intimate. Loaded with state-of-the-art technology – both in terms of sound and lights – and with configurable seats – depending on the nature of the event. AVAI also arrives as a smart and spiffy answer to the post-pandemic world that finds its presence in a digital world; where performing arts are increasingly reaching audiences through online portals and platforms. With a dual identity – both offline and online – AVAIl also allows us the potential and possibility of not merely meeting and curating events, in real-time but also translating that experience, online, through the AVAI platform on www.apasarasarts.com We are excited about AVAI; all that it stands for; of connections, offline and online.

Thursday Talkies – @akumarasamy

“in conversation on anything and everything about dance” An Instagram bi-series which began in February 2021, on the first Thursday of the monthat 8pm SGT has taken the classical dance industry by storm. Moderated by Aravinth Kumarasamy and Seema Hari Kumar, each 30 minute session features a discussion topic on current trends and issues in dance. In February, they discussed the topic, ” Choreography and what it means today”. In March, they discussed the topic, ” Guru-shishya relationship.” In April, the topic was ” Price of Art – How much do you pay? where the session introduced guest speakers (& mystery guests!). Anil Srinivasan and Vidhya Nair shared their view points. In May, the topic was ” Professionalism vs Amatuerism in Dance – how do we draw the line & what are the experiences of performers and rasikas?. Guest speakers Mohanapriyan Thavarajah and Sreedevi Sivarajasingam shared their experience. In June, the topic was ” The big “A” – exploring the intent, benefit and relevance of an Arangetram.” The session explored clarifications on how the teacher, student and parents can align expectations while having a rewarding journey. The session had Gayatri Sriram and Shankar Kandasamy as guest speakers. In July, the topic ws ” The Place for a Male” in Bharatanatyam featuring two male dancers – Christoper Gurusamy and Parshwanath Upadhye who spoke passionately about challenges and advantages they fare in the industry and in choosing this profession. Each session garners more than 500 views and features live questions from a live audience and is recorded for delayed viewing. Many viewers have feedback that this style of informal discussion allows for different perspectives to be shared in a frank and informal manner and for many its been an interesting way to hear alternative views and unpack some of the grievances and concerns which are often unspoken. The next session will be on 5th August on Instagram @akumarasamy at 8pm SGT.

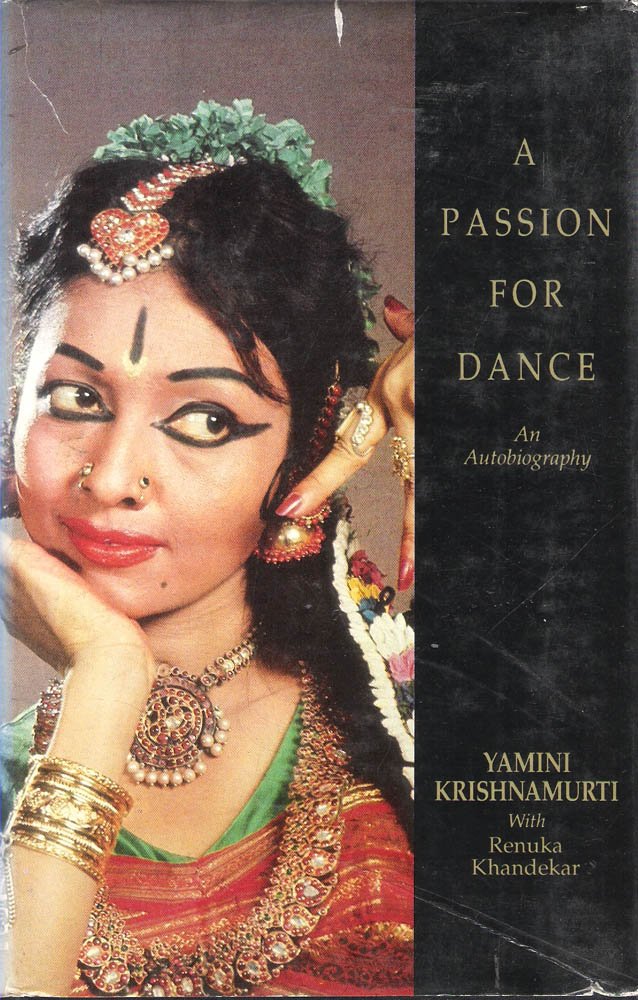

A Passion for Dance

Yamini Krishnamurti With Renuka Khandekar Yamini Poornatilaka Krishnamurti, a little tomboy growing up in the temple town of Chidambaram, felt strangely drawn towards the dancing figures sculpted on the temple walls. When the time came for her to settle down to a formal school education, she astonished her family by declaring she would rather learn dance at Kalakshetra, the dance school established by Rukmini Devi Arundale. It was to be a long and arduous journey, but Yamini’s uncompromising commitment to her art and her father’s unstinting support saw her blossom into one of India’s greatest Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi dancers. In this book, Yamini describes her art as “transforming, redeeming and intoxicating” She speaks of her experience as a young girl growing up in an orthodox South Indian family, her tutelage under Rukmini Devi Arundale, her awe at watching Balasaraswati perform, her romance with Kuchipudi, till then a male bastion, and her memories of her many performances in India and abroad. Embellished with her favourite stories from a legend and folklore, spiked with personal anecdotes and comments on changing public tastes and sensibility , this book is truly a daner’s tribute to her art: Yamini Krishnamurti describes herself as ‘Andhra by extraction, Karnataka-born and Tamil by training.’ She was one of the most distinguished pupils of the Kalakshetra school of music and dance in Madras. She pioneered the national and international recognition of the classical dance styles of Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi and became the youngest recipient of the Padma Shri in 1968. The Tirupati Temple appointed her as ‘Asthana Nartaki’, its official dancer, the only modern instance of a temple claiming an artiste. Renuka Khandekar is a writer for print & television. After having lived and travelled widely in Europe for two years, she chose to come back to India instead of going further west, ‘to share in the change and excitement of a restaurant place called home’. Co-authoring Yamini Krishnamurti’s life story was a two-year project that she likens to ‘participating in a great yagna or ritual sacrifice’.

To Help Us Survive This Agony, Classical Arts Must Be Authentic Not Tokenistic

As the world settles into a cautious new normal, practitioners of classical dance and music can contribute to replenishing our inner reserves. By Malavika Sarukkai India is breathless and in agony as its people struggle to come to terms with the pandemic and its toxic fallout. The images of death and despair that flood the media scream for our attention. In the last few months, the second wave of COVID-19 has broken the spirit of India’s millions as it continues its destructive trail into rural India as well. At this juncture, our hope is that vaccinations administered across a sizeable population will halt the spread of the virus. The only encouraging sign is that in other parts of the world, the strategy of large vaccination drives is returning the world back to a cautious ‘new normal’. The last few months of the second COVID-19 wave made us face some harsh truths. It made us see the urgency of valuing human life, acknowledging privilege and admitting to the harsh disparity that separates the haves and the have nots. The pandemic has revealed yet again that a large part of India lives perilously and on the edge. It is important to come to terms with the gross inequality that marks our reality. Equally, it is important to understand that as a society, what is most needed is empathy together with swift and thoughtful action – both individually and collectively. We must see that humanity connects us all. Just as the image of thousands of migrant workers fleeing the cities for their villages last year left an indelible imprint on our conscience, imploring us to recalibrate the way we think, relate, act and live, the tragedy of the pandemic claiming so many lives in its second phase has reinforced that we cannot survive in isolation – as a society, those who are privileged must be attuned to the problems of those who are not. Only then will we be able to see the greater ecosystem beyond ourselves, recognise the humanity in all. To that extent, the pandemic has highlighted the need to change the way we think, by moving away from the easy route of tokenism – sending, or forwarding, outpourings of concern on social media – to the more difficult route of taking the right action at the right time so that people can start rebuilding their lives. What is clear is that in a post-COVID-19 world, our ravaged world, the word ‘human’ can no longer be used without stirring our conscience. Being human is being aware, sensitive, empathetic, responsible and ethical. The artistic community, like others, is going through turbulent times and facing an uncertain future. All paradigms of stability and continuity have been virtually dismantled in the time of COVID-19. The complete stalling of live performances has brought with it an uneasy silence and desperation for artistes who are struggling to survive. It is apparent that we need to renegotiate structures in our personal and professional lives to make sense of a post-COVID-19 world. The challenge to transform demands holistic action from us – as people and as artistes and, in this article, I look at the world of dance in particular. Practitioners of both classical and folk dance from across the country have been gravely affected by the pandemic. Many have lost their livelihoods, lost family, become orphaned, lost dignity, courage, and the earnings of a lifetime. The pandemic has ruthlessly cut through the socio – economic fabric, unmindful of the privileged and the less fortunate. Several, without even the basic means to healthcare, have lived a nightmare too terrible to even imagine. The pandemic, which has left a trail of devastation in its wake, has made us see that for our planet and its human inhabitants, the only way out is to move towards the idea of creating an inclusive space— not as mere tokenism but as an honest engagement. A space where we don’t speak from the high ground of judgment and finality but allow plurality, flexibility, empathy and understanding to guide our actions. The kind of space that does not need an external conscience keeper but demands of us that we make ourselves conscientiously accountable. A space that prompts us to course correct and move towards a fair and equitable world. This forced pause could then be viewed as a window for artistes to review their repertoire, ask themselves why they do what they do, challenge the status quo of the tried and tested comfort zone, reflect seriously on the responsibility of inheriting a tradition and, where necessary, question tradition itself with an informed sense of responsibility, to bring it closer to its essential core by peeling away clichéd decorations. Authenticity, not tokenism During the pandemic we have seen the sheer hollowness of tokenism – when the seriousness of the second COVID-19 wave was not acknowledged, prompt action not taken, leaving India unprepared for the magnitude of death and devastation that has ravaged the people. At the same time, we have also seen that when people step out and act in real time and on the ground, the difference it makes is monumental – as in the case of doctors, healthcare workers, nurses, ambulance drivers, paramedics, NGOs, etc. We owe them and the scientific community a lifetime of gratitude. Perhaps there is a lesson to be learnt from this – as people and as artistes. For serious artistic enterprise, being authentic is vital. If one is not alert, the repetition that classical dance involves could bring with it a sense of false accomplishment, where habit and muscle memory, rather than a mindful awareness in the body, take over. This superficial practice gives a sense of achievement but does little to deepen the study of dance in the body. If we wish to move away from tokenism to find the real pulse of dance, we must explore how we can make our dance lived, inhabited. The question then is – can we distance ourselves from this

Breaking the Sound Barrier – the Sai Shravanam way

on June 20th 2021 Sai Shravanam shared insights on how he creates a musical score and demonstrated with his latest work “Rivers of India” released two months ago. This provided a detailed look at how voices, instruments are merged and synthesised and creative elements get incorporated in his creations resulting in a fresh perspective coherent with corresponding images which resonate and make the audience feel transported by the soundscape. He shared stories about working with A R Rahman and how recording takes place in his studio and the challenges caused in remote recording during the pandemic lockdown. More than 70 enthusiastic viewers and music students engaged in the Q&A. It was an inspiring session.