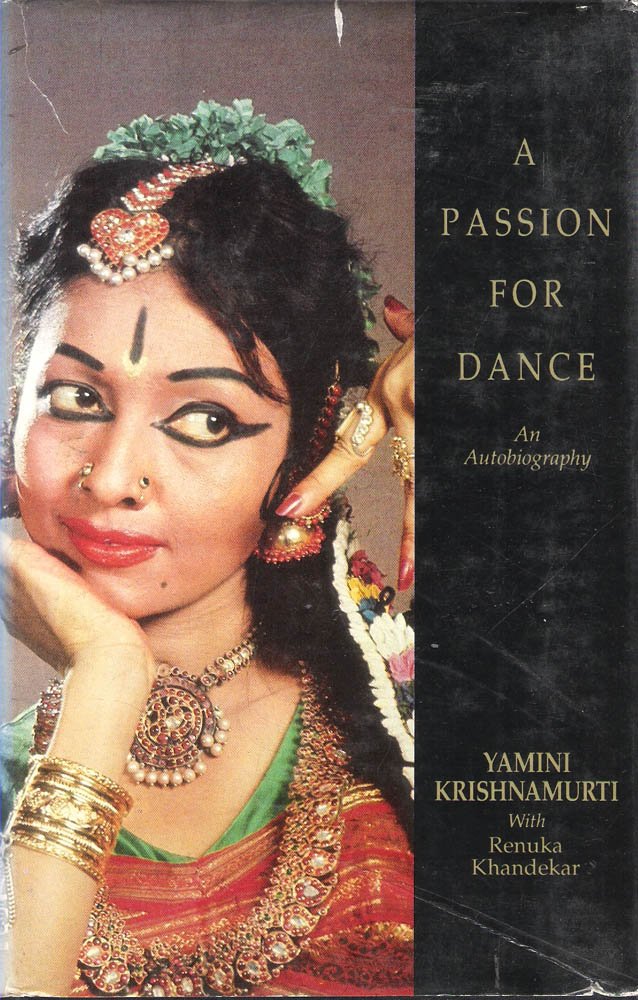

A Passion for Dance

Yamini Krishnamurti With Renuka Khandekar Yamini Poornatilaka Krishnamurti, a little tomboy growing up in the temple town of Chidambaram, felt strangely drawn towards the dancing figures sculpted on the temple walls. When the time came for her to settle down to a formal school education, she astonished her family by declaring she would rather learn dance at Kalakshetra, the dance school established by Rukmini Devi Arundale. It was to be a long and arduous journey, but Yamini’s uncompromising commitment to her art and her father’s unstinting support saw her blossom into one of India’s greatest Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi dancers. In this book, Yamini describes her art as “transforming, redeeming and intoxicating” She speaks of her experience as a young girl growing up in an orthodox South Indian family, her tutelage under Rukmini Devi Arundale, her awe at watching Balasaraswati perform, her romance with Kuchipudi, till then a male bastion, and her memories of her many performances in India and abroad. Embellished with her favourite stories from a legend and folklore, spiked with personal anecdotes and comments on changing public tastes and sensibility , this book is truly a daner’s tribute to her art: Yamini Krishnamurti describes herself as ‘Andhra by extraction, Karnataka-born and Tamil by training.’ She was one of the most distinguished pupils of the Kalakshetra school of music and dance in Madras. She pioneered the national and international recognition of the classical dance styles of Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi and became the youngest recipient of the Padma Shri in 1968. The Tirupati Temple appointed her as ‘Asthana Nartaki’, its official dancer, the only modern instance of a temple claiming an artiste. Renuka Khandekar is a writer for print & television. After having lived and travelled widely in Europe for two years, she chose to come back to India instead of going further west, ‘to share in the change and excitement of a restaurant place called home’. Co-authoring Yamini Krishnamurti’s life story was a two-year project that she likens to ‘participating in a great yagna or ritual sacrifice’.

To Help Us Survive This Agony, Classical Arts Must Be Authentic Not Tokenistic

As the world settles into a cautious new normal, practitioners of classical dance and music can contribute to replenishing our inner reserves. By Malavika Sarukkai India is breathless and in agony as its people struggle to come to terms with the pandemic and its toxic fallout. The images of death and despair that flood the media scream for our attention. In the last few months, the second wave of COVID-19 has broken the spirit of India’s millions as it continues its destructive trail into rural India as well. At this juncture, our hope is that vaccinations administered across a sizeable population will halt the spread of the virus. The only encouraging sign is that in other parts of the world, the strategy of large vaccination drives is returning the world back to a cautious ‘new normal’. The last few months of the second COVID-19 wave made us face some harsh truths. It made us see the urgency of valuing human life, acknowledging privilege and admitting to the harsh disparity that separates the haves and the have nots. The pandemic has revealed yet again that a large part of India lives perilously and on the edge. It is important to come to terms with the gross inequality that marks our reality. Equally, it is important to understand that as a society, what is most needed is empathy together with swift and thoughtful action – both individually and collectively. We must see that humanity connects us all. Just as the image of thousands of migrant workers fleeing the cities for their villages last year left an indelible imprint on our conscience, imploring us to recalibrate the way we think, relate, act and live, the tragedy of the pandemic claiming so many lives in its second phase has reinforced that we cannot survive in isolation – as a society, those who are privileged must be attuned to the problems of those who are not. Only then will we be able to see the greater ecosystem beyond ourselves, recognise the humanity in all. To that extent, the pandemic has highlighted the need to change the way we think, by moving away from the easy route of tokenism – sending, or forwarding, outpourings of concern on social media – to the more difficult route of taking the right action at the right time so that people can start rebuilding their lives. What is clear is that in a post-COVID-19 world, our ravaged world, the word ‘human’ can no longer be used without stirring our conscience. Being human is being aware, sensitive, empathetic, responsible and ethical. The artistic community, like others, is going through turbulent times and facing an uncertain future. All paradigms of stability and continuity have been virtually dismantled in the time of COVID-19. The complete stalling of live performances has brought with it an uneasy silence and desperation for artistes who are struggling to survive. It is apparent that we need to renegotiate structures in our personal and professional lives to make sense of a post-COVID-19 world. The challenge to transform demands holistic action from us – as people and as artistes and, in this article, I look at the world of dance in particular. Practitioners of both classical and folk dance from across the country have been gravely affected by the pandemic. Many have lost their livelihoods, lost family, become orphaned, lost dignity, courage, and the earnings of a lifetime. The pandemic has ruthlessly cut through the socio – economic fabric, unmindful of the privileged and the less fortunate. Several, without even the basic means to healthcare, have lived a nightmare too terrible to even imagine. The pandemic, which has left a trail of devastation in its wake, has made us see that for our planet and its human inhabitants, the only way out is to move towards the idea of creating an inclusive space— not as mere tokenism but as an honest engagement. A space where we don’t speak from the high ground of judgment and finality but allow plurality, flexibility, empathy and understanding to guide our actions. The kind of space that does not need an external conscience keeper but demands of us that we make ourselves conscientiously accountable. A space that prompts us to course correct and move towards a fair and equitable world. This forced pause could then be viewed as a window for artistes to review their repertoire, ask themselves why they do what they do, challenge the status quo of the tried and tested comfort zone, reflect seriously on the responsibility of inheriting a tradition and, where necessary, question tradition itself with an informed sense of responsibility, to bring it closer to its essential core by peeling away clichéd decorations. Authenticity, not tokenism During the pandemic we have seen the sheer hollowness of tokenism – when the seriousness of the second COVID-19 wave was not acknowledged, prompt action not taken, leaving India unprepared for the magnitude of death and devastation that has ravaged the people. At the same time, we have also seen that when people step out and act in real time and on the ground, the difference it makes is monumental – as in the case of doctors, healthcare workers, nurses, ambulance drivers, paramedics, NGOs, etc. We owe them and the scientific community a lifetime of gratitude. Perhaps there is a lesson to be learnt from this – as people and as artistes. For serious artistic enterprise, being authentic is vital. If one is not alert, the repetition that classical dance involves could bring with it a sense of false accomplishment, where habit and muscle memory, rather than a mindful awareness in the body, take over. This superficial practice gives a sense of achievement but does little to deepen the study of dance in the body. If we wish to move away from tokenism to find the real pulse of dance, we must explore how we can make our dance lived, inhabited. The question then is – can we distance ourselves from this

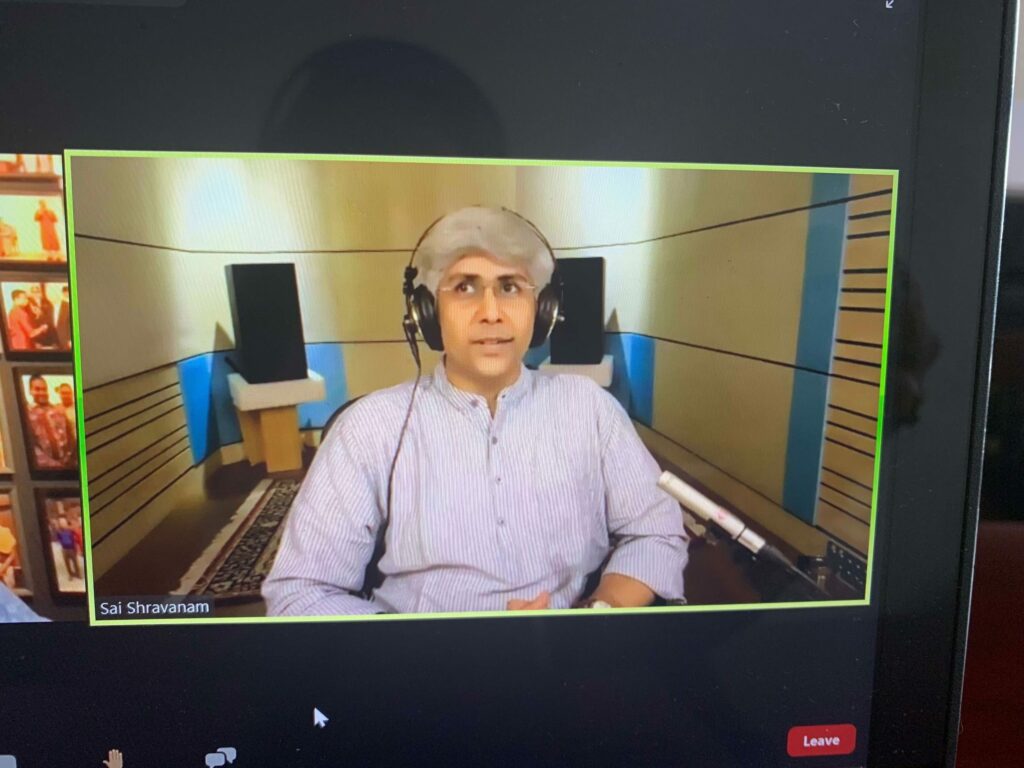

Breaking the Sound Barrier – the Sai Shravanam way

on June 20th 2021 Sai Shravanam shared insights on how he creates a musical score and demonstrated with his latest work “Rivers of India” released two months ago. This provided a detailed look at how voices, instruments are merged and synthesised and creative elements get incorporated in his creations resulting in a fresh perspective coherent with corresponding images which resonate and make the audience feel transported by the soundscape. He shared stories about working with A R Rahman and how recording takes place in his studio and the challenges caused in remote recording during the pandemic lockdown. More than 70 enthusiastic viewers and music students engaged in the Q&A. It was an inspiring session.

YAVANIKA – INTERVIEW WITH PRIYADARSINI GOVIND

By Vidhya Nair VN: What motivated you to create Yavanika? What was your inspiration? Walk us through your process, from how you got the idea to the concept evolving, the director’s vision and what it was like to dance for the camera. PG: I had been wanting to work on a group production for some time. Last year, I was supposed to present a group production at DIAP but it didn’t happen. As I have always been a soloist and duo presenter, this time I had to think differently. I first started with different concepts & ideas. Then I landed on Kabir’s “Jheeni.” [ Kabir Das was a 15th century iconoclastic Indian poet-saint revered by Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. He was raised and adopted by a Muslim weaver] My concept deals with the body as likened to a cloth and the journey of the being, life on earth and the return back to the Maker. Slowly, the concept came into play. “Yavanika” means screen, cover. I have also incorporated the idea of “Maya”- the illusion of what we believe to be real. The compositions I have used engage with the five elements within us and outside of us and we explore the screen as the body. A traditional repertoire was choreographed. The opening Alarippu focuses on our energies, then the concept of Samsara which refers to the cycle of the body’s rebirth and death and how it pleads to be delivered from Maya. Then the Thillana shows the uptake of physical energy as the soul dances out of the body and a finale showing the creation of the cloth as it returns to the Maker. Dancing to the camera is not new to me. I’ve had a lot of experience facing the camera as I had done many teaching DVDs over the years. I also have been doing a lot of work online. It was a deliberate choice to not do this as a choreographed dance performance but to present it in the eyes of a cinematographer. It is a highly subjective point of view as there is no end to the ways one can capture dance on camera but this medium is able to traverse the stage and can bring the audience’s eye to certain moves. Without too much interference with the compositions or movements in the dance pieces, we have filmed it such a way that makes it very different from watching a stage performance. I had engaged a filmmaker and cinematographer for this film. As people outside the dance world, they actively watched rehearsals and understood how dance is being performed. The film is a coming together of how they view through their camera lens and culminates both our visions as choreographer and filmmaker in the final outcome. VN: What is unique about Yavanika, and about blending seer-poetry with classical dance? PG: This was an attempt between what you can see on stage and what a camera can show. It is not meant to take away from the in-person experience but we are trying to use the advantages we have with this technology. It so happened that we have used compositions of different languages and applied philosophical questions about Samsara as life on earth. We looked at the parts of everyday life which are very real and connected it with the seer’s questionings on life and reality. We used a variety of approaches and put them on camera. VN: Why is it important for you to make this film at this point in your career? PG: I am not looking at points in my career. Today’s times bring out a trigger and opportunity to create. It was always something I wanted to do; it has been in my mind for some time. IPAC and Aravinth Kumarasamy (Curator & Convenor) provided me the basis to actually do it. VN: What do you think about programs like IPAC in keeping Indian arts and culture thriving outside of India? PG:There are now no geographical boundaries. It no longer matters which part of world this is being organised. Our world has become porous. What is important is that there should be vision in the programming and adequate resources to enable delivery. IPAC has made it available to students these past ten years. It also because of IPAC that Yavanika came to be created. A trigger and an incentive to try things out and providing a platform for it. Knowledge is essential for dancers and in trying to provide a varied experience and resources is unique about IPAC. Aravinth Kumarasamy is very tuned in to what artistes and students need. IPAC is crucial for evolution of art. Now, it no longer matters where the location is. IPAC gives access to both students and artistes. Organisation is important for the arts to grow. The vision of the program, access, resources and the opportunities it creates. VN: As a mentor in IPAC how do you connect/ engage with the younger generation and how do you feel about the potential of Singapore artists? PG: Mentoring has been a fantastic experience; it is an important way of guiding the journey of an artiste. It is not about teaching them what to do or choreographing for them but is about helping them discover and channelise their creative thoughts. My role is to help them find it in themselves and discover what kind of artiste they are capable of becoming. The young dancers of Singapore are fantastic. The kind of concepts and movements they think up has been very exciting for me. It’s not easy to do, fleshing out a concept, visualising and giving it movement, its like incubating and delivering your baby. All this requires commitment and resilience. Whatever facilities and resources provided; the majority of work has to be done by the young artiste to bring visualisation to their ideas. All the girls have been different. Each very committed. To create your own work is also an emotional journey. There is self-doubt, frustration, and discovery. From understanding how to

TANJORE THE GOLDEN AGE OF BHARATANATYAM

Reminiscences by Lakshmi Viswanathan It seems like yesterday…..a full house, with eager expectations at the Esplanade in Singapore when Aravinth Kumaraswami of Apsaras Arts presented a tribute to Tanjore as a highlight of Dance India Asia Pacific 2016. It is said, ideas should not be kept but used effectively. Aravinth’s idea of making several students perform what they had learnt from various teachers in the preceding years as a tribute to the roots of these dances in the magnificent culture of Tanjore, flowed as a stream of inspiration to me in Chennai. He asked me if I would be the presenter of this show. I told him, I have an idea, but let it be a surprise until we are on stage. While the dancers were in full rehearsal, I merely watched, only giving cues about my entrances and exits between the dances. What was I going to do? Well, that is my story as I write this. Studious as always, I had, during my research of Tanjore dynasties, come across a dynamic royal personality. She was Kamakshibai Sahiba, the last Maratha queen of Tanjore, and one of the wives of Sivaji, the last ruler. I decided to be Kamakshibai, dressed in traditional Marathi style, complete with accessories, and dance to centre stage in the Lavani style, between each dance and tell the story of Tanjore from Raja Raja Chola to the final Maratha rule of Tanjore. The Marathas, descended from Chatrapathi Sivaji, were devoted to the Mother goddess Bhavani. So my entries were accompanied by a famous Bhimsen Joshi bhajan in a lilting thisra beat ” Jai Durge….matha Bhavani”. My moves were in suitable Lavani style, typical of Marathi dance. As Raja Raja was an incomparable Shiva bhakta, the invocation dance by a group was the Shiva Panchakshara Stotra. I spoke as the story teller or Shabdkosh ( Sanskrit for racounteur). As the story of the great king unfolded in my speech, I shared nuggets of information about his patronage of dance, employing four hundred dancers to serve Brihadeeswara, and how his whole kingdom was ruled by Adavallan ( Nataraja) the lord of the dance. The anecdote of Raja Raja rediscovering the Thevaram hymns, in dusty bundles of palm leaves in the Chidambaram temple, and his edict to make the singing of these hymns in all the temples of his kingdom compulsory made a suitable impact on the listeners. To enhance this story Mohanapriyan glided on to the stage to perform select verses from the Thevaram anthologies, underlining the glory Shiva in Tanjore under the great king Raja Raja, and the everlasting relevance of the saints Appar, Sundarar, and Tirugnanasambandar. My narrative touched upon the hundred dark years when Tanjore came under a series of alien conquests. Then, I glorified the Renaissance which originated in the city of victory, Vijayanagaram. The new dynasty were known as the Nayaks. As a wave of renewal and re- building spread across the kingdom, the kings patronised savants, poets, dancers, musicians and new temples. Raghunatha Nayak was an artist himself who modelled a new Veena. The Nayak court’s prime minister Govinda Dikshitar proved a great administrator. His son Venkatamakhi produced the resounding Melakartha classification of the Ragas of Carnatic music. And Kshetragna whose poems we do Abhinaya for, came to the court of Vijayaraghava Nayak and composed many Padams in his honour. Natyam was in full and dynamic splendour in temple and palace. The marvellous shrine for Subramanya ( Murugan) built within the vast grounds of the Brihadeeswara temple is to this day an icon of Nayak architecture and devotion. Seamlessly, my narrative flowed into the Skanda Kauttuvam presented by a set of agile dancers, making patterns of fluid Nrtta on the colourfully lit stage as a tribute to the gods and the sanctity of their abodes. Mannargudi and SriVidya Rajagopala the presiding deity has alwayss been a favourite of devotees, poets, composers. The Nayak kings expanded this famous and vast temple, making it a landmark of their kingdom. Hailing from a small village called Oothukkadu near Tanjore, the great Vaggeyakar Venkatasubbayyar was a prolific composer of songs in praise of Krishna. He was a devotee of Mannargudi Rajagopala .Worthy of visualising them as dance, his compositions are popular to this day. Three sparkling dancers performed the Kalinga Narthana composition of this great composer taking the audience with them with fluid movements. With pride and joy, I recounted the roots of Bharatanatyam as we know it today to the times of the Maratha dynasty that followed the Nayak rule of Tanjore. The glory of music and Natyam was promoted zealously by the Marathas who brought their own cultural ethos to Tanjore. The four renowned Nattuvanars known as the Tanjore Quartet were right there, patronised by each king. They were composing and conducting premieres of their great Pada Varnams, danced by young talented Devadasis in the grandeur of the palace. The Marathas were also devoted to Tyagesar the deity of Tiruvarur. Linking devotion to Sringara the court Gurus excelled in creating a new format, a trend for performance, which is stylish to to this day. The inimitable Bhairavi Pada Varnam Mohamana in Tamil was presented as a solo with a combination of Bhakti and Sringara pervading the dance. It was the best acknowledgment of the Paramapara of Nattuvanars. As Kamakshibai, I shared many an anecdote about the Maratha legacy still found in many aspects of Tanjore culture….the devotional music, Harikatha, the congregations of Bhajana singing, the Maths of religious heads, the inclusion of Hindustani musical modes and various crafts including the now proverbial Tanjore painting. With understandable pride, I said that the Tanjore Quartet have left for posterity their finest Varnam in praise of Sivaji the last king – Dhanike in Raga Todi. With verve and vigour a group presented the finale, a Thillana. Perhaps even this musical piece known as Tarana in the north, was adapted to Bharatanatyam by the great Gurus with royal approval! Thus the curtains came down with loud

Sound of Silence – Rajkumar Bharathi’s Musical Quest

By Asha Krishnakumar Simple, genuine, gifted, resilient… These are the words used most often to describe Rajkumar Bharathi, the great -grandson of Mahakavi Subramanya Bharathi, the legendary litterateur whose fiery writings stoked the patriotic fire of the people fighting colonial rule. Rajkumar has carved a niche for himself in the music world without leaning on his illustrious lineage. More than 100 people have been interviewed, associated closely with Rajkumar over the years. A common thread by all of them is how Rajkumar is an extraordinary person. In discovering him, the author finds a tale of genius, resilience and humility that needs to be told. In documenting Rajkumar’s life and his musical journey is an enlightening experience at every level – intellectual, philosophical, rational, emotional, spiritual and human. This book was written with the intent to inspire youngsters to take life in their own hands. To be resilient in the face of adversity. To be humble even when you feel like you have conquered the world. To be humane even when you feel the whole world is against you. Rajkumar Bharathi’s life is a true inspiration at various levels.

Memories of an Odissi-dancer-to-watch from the International Dance Festival at Bengaluru

By Soumee De Early on a chilly January morning, when I landed from sunny Singapore at the Bengaluru airport, I was both anxious and excited to be represent Singapore at the International Dance festival, hosted by World Dance Alliance Asia Pacific, Karnataka chapter at the prestigious Seva Sadan at Malleswaram. The three-day festival in January 2010 featured dancers from India, USA, Malaysia and Singapore presenting Bharatnatyam, Odissi and Kuchipudi. I had the honour of sharing the stage with Navia Natarajan from USA on January 10th evening session. What touched me was the warmth of the organisers who inspirational performers (Mrs Veena Murthy Vijay, Mrs Anuradha Vikranth, Mrs Sharmila(di) Mukerjee) and their respect, care, thoughtfulness towards each performer. From the warm welcome at the entrance of Seva Sadan premises, to personal introductions to the hall-packed audience, from introducing us to the media critics to managing the logistics seamlessly – lights, video and photography. The seasoned professional artistes and Gurus who curate and select the dancers from around the globe, also take care that the experience of both the performer and the Rasika happen to be authentically delightful. While the trip was full of emotional highs, I learnt insightful lessons about the life of a performing artiste during this momentous trip. The next morning, I woke up to this surprise review comment by the musician-art critic, Mysore V Subramanya in the Deccan Herald! “Soumee De Girotra, who gave a Odissi dance recital in the World Dance Alliance, is from Singapore. Young and enthusiastic Soumee De has practiced Kathak, Ravindranrithya and Music, apart from Odissi. She opened her recital with Mangalacharan, customarily, followed by Thrikandi Pranam. She performed the pallavi gracefully with the lilting nritta. With all the physical graces needed for dance she presented the astapadi of Jayadeva neatly. Her ‘Dashawathara’ was also attractive. Soumee De is undoubtedly an Odissi dancer to watch.” Little did I know that in a few months I will discover the joy of motherhood. This memorable dance travel diary marked my last trip overseas to perform. A decade later, with two adorable sons, I feel nostalgic remembering the highs-lows of traveling with dance-only luggage. On an optimistic note, I feel fortunate that we have opportunities to perform and teach our classical art forms here at Singapore. Below are two links to the of reviews posted about the dance performances in detail. Hope you will enjoy this walk down the memory lane, as much as I did writing about it! 1. Deccan Herald review 2. Narthaki review