Cover Story

Someone famous once said: “You are not alone in this world; you are part of an ensemble”. For decades now, a whole host of Bharatanatyam artistes have poured their creative imagination and energies into creating ensemble work that has not only brought to the fore a slew of artistic ideas and expressions but also in bringing together an array of dancers and collaborators who are invested in a common project, these dancers-choreographers-teachers who envisage an ensemble are perfect examples of the meaning and essence of the word, collaboration. In this edition, we raise a toast to those who have dedicated their dance careers to the creation, production and presentation of ensemble work. We shine the spotlight on four Bharatanatyam exponents from Chennai – Anitha Guha, Jayanthi Subramaniam, Radhika Shurajit and Sheela Unnikrishnan. Read on for a detailed interview where each of these artistes, responds to a common set of four questions ANITHA GUHA “Despite a series of challenges in creating ensemble work, what keeps us going is passion. It is the driving force that enables us to overcome obstacles and create magical productions,” says Chennai-based Bharatanatyam exponent, Anitha Guha A fantastic group presentation always weaves together several key elements: captivating storytelling or a cohesive theme, brilliant choreography, beautiful dance styles, extraordinary coordination and precision, a well-chosen cast of artistes who perfectly fit their roles, enchanting music, enhanced lighting techniques, aesthetic props, vibrant costumes, exquisite jewelry, and stunning make-up… Together, these components create a magical experience. Our storytelling, rooted in the rich tapestry of the Puranas and Ithihasas, reaches out to the younger generation, providing a joyful and educational experience. It also offers them a platform to showcase their talents. The ensemble format I have chosen is the traditional Nritya Natakam, which provides immense scope to learn various stories from our Puranic characters, understand their unique body language, and explore a wide range of emotions. This holistic approach not only preserves our cultural heritage but also ensures its relevance for future generations, creating a bridge between the past and the present through the magic of performance. First and foremost, a thorough study of the literature we plan to present is essential. Sometimes, this involves consulting a well-learned scholar for deeper insights. As I read or hear about the material, I naturally envision the production—it is God’s gift to all choreographers, I believe. Next, I identify the major scenes to be emphasized and approximately plan the duration of each segment. Dancers are selected for various roles based on their talent, commitment, and suitability for the characters. Meanwhile, we choose suitable texts for the lyrics or create new ones, and work with renowned music composers to craft appropriate rhythms and diverse musical interludes. It’s worth noting that sometimes choreography is developed first, with the music composed later to match the dance sequences. Once the baseline is set, I start choreographing with my students. Group sequences are choreographed, taught, and practiced diligently. To be honest, choreography often happens naturally, inspired by excellent music. Simultaneously, each character’s role is individually developed with the dancer. We also design costumes, select good jewellery, plan lighting, and arrange props as needed. After rehearsing for a minimum of two to three months, we are ready to present on stage. Typically, a production takes six to eight months or even a year to complete. However, there have been instances where a smaller production was put together in just 15 to 20 days. The first challenge is, of course, securing the necessary funds. A production requires substantial financial support. Funding can be divided into two categories. The first is the initial production costs, which include remuneration for professional dancers and musicians, costumes, jewellery, audio recording, props (if used), lighting, stage rehearsal charges, make-up, et al. Once the production is ready to be performed at different venues, the expenses, except for the musicians’ remuneration and audio recording, remain the same or can even double, especially for out-of-town performances. Unfortunately, except for a few organizations, most do not provide sufficient compensation, forcing artistes to find sponsors to support their endeavors. Another major challenge is the availability of the same artistes for every program. Consequently, choreographers and teachers must constantly adapt, working with different dancers to bring the production to life. Finally, before a performance, it is crucial for dancers to have a stage rehearsal. Completing the light design within the limited time available also poses a significant challenge. Despite these challenges, what keeps us going is passion. It is the driving force that enables us to overcome obstacles and create magical productions. Parishvanga Pattabhishekam, which we presented in Cleveland, has been my most challenging production to date. It was my first production in the United States of America and involved a collaboration with many dance gurus, their students, music composers, and musicians. I was working with the esteemed music composer, Sangeetha Kalanidhi Sri Neyveli Santhanagopalan. Both he and I had numerous season commitments, and we had to complete this enormous project within just two months. This was quite a challenge. As the production was a collaborative interpretation of the Ramayana, each participant focused on one or two kandams. We had to share time, space, the orchestra, and rehearsal sessions with everyone involved. For many years, I had been working within the comfort zone of my own class, students, and my own time and space. This new venture pushed me far beyond those boundaries, causing considerable worry. However, the program was eventually presented and was received extremely well by the audience. This success was a testament to the hard work and collaboration of all involved.ANITHA GUHA Jayanthi Subramaniam“Ensemble work is like many people performing but with a single mind. This harmony is what creates magic,” says Chennai-based Bharatanatyam exponent, Jayanthi Subramaniam The magic of the ensemble lies in the sheer energy that can be created by the coming together of artistes who are in perfect sync with each other – physically, mentally and emotionally. Ensemble work helps you develop as an artiste and

COVER STORY

Let’s Talk Conservation Two young and talented Bharatanatyam artistes, Mahathi Kannan and Manasvini Ramachandran, share their interest, journey in working with the tangible and intangible in the arts… An interview Qus : What has been your fascination with the idea of heritage? When did you know that you wanted to study it formally and pursue a career – of sorts – in it?Mahathi: I consider it a blessing that I was able to grow up in an environment which induced in me a love and interest in anything heritage-related. My revered Guru and grand-aunt Dr Padma Subrahmanyam is the one who cultivated in me a special interest in temples and sculptures. I initially wanted to pursue archaeology but later I found my leanings specifically towards art history. I got an opportunity to do my Masters in art history from the National Museum Institute, New Delhi, which gave better structure to my perception and study of the subject. That has, since then, opened new possibilities for me to apply that knowledge to my dance as well.Manasvini: My family hails from a village called Korukkai in the Thanjavur district. Migration to the city happened two generations ago with no connection to our roots. To re-establish our connection, we drove down to the village as a family and came across a 11th CE chola temple which was neglected. Dr Nagaswamy made a visit to the temple and read the stone inscriptions. After pestering mama as a ninth grader, he taught me the chola grantha script. Dr Nagaswamy introduced me into the realms of art, history, and archaeology. I have always leaned toward Indic culture and heritage but never actually thought I would make a career out of it. It was in my MFA (Bharatanatyam) that a world of possibilities was opened up to me by Dr Padma Subramanyam (Akka) and the faculty of SASTRA university. Being a student of arts and science, both being vastly different from each other, I’ve always wanted to tread a path in between the two. I found conservation to be a beautiful blend of the two and saw this as my calling. Qus : As an artist, does it help that you have the heart-for-the-arts? How does empathy add value to the work that you do?Mahathi: It definitely does help! Empathy helps develop sensitivity. In my understanding as a student of art history, that sensitivity is important to recognise and understand the nuances and sentiments behind works of art. However, it is also important to maintain a certain amount of objectivity since facts of history also need to be taken into consideration. It is this balance that I am trying to develop in my approach towards art history as a subject and art as a whole.Manasvini: To work on an object, it is important for a conservator to understand it from different perspectives. Beyond an understanding of how it was made, the materials used, and the techniques employed in the making, a conservator must understand why it was made and its significance. Any artist understands the purpose of art better than a person who cannot appreciate art. My professor used to insist that we first look into the artwork before actually finding out what issues it has. Being a dancer surely helps me understand this nitty gritty better. Qus : Can you break down the work that you do or plan to pursue in the space of heritage and conservation of the arts?Mahathi: I must admit, I am not extremely active in the art history space but I do try to do my bit in sharing whatever knowledge I have gained and continue to gain through my page Shilpakatha. It is a humble venture through which I simply would like to share the joy I experience in art, specifically Indian sculpture. Studying each sculpture that I post about involves quite a bit of work for me, since I feel I have a responsibility of sharing knowledge in the most authentic, honest manner. For instance, when I am looking into any legend associated with a deity or a temple, I try to go into the source(s) of the legend such as the Itihasas and Puranas. Reading up the original texts with their translations and correlating them with the iconography of a sculpture. This is my most favorite part of the whole process. It is such an amazing learning experience and this is the experience that I try to pass on through my posts on Shilpakatha.Manasvini: Simply put, conservation is the process of helping to see historic or art objects better and making them last longer. Every object when created has a life span until it perishes. It is for the conservators to help prolong the life of this object. As conservators, we take a very clinical approach to our objects to make sure that the treatment administered is appropriate as once done, it is hardly reversible. A conservator draws a condition report with a visual glossary of the deterioration patterns. While doing this, she also understands the making of the object, its history and significance. The object is then imaged using different radiation sources like Ultra-Violet (UV) and Infra-red (IR) rays which are great investigative tools in understanding conservation. Treatment for the object is chosen based on the deterioration patterns and materials employed are conservation grade materials. This step will involve cleaning, mending, lining and retouching depending on what is best and necessary for the object. Qus : Talk to us about the tangible and the intangible in the arts?Mahathi: I find art history to be a very unique blend of the tangible and intangible aspects of art. We study temples, sculptures and artefacts, all examples of tangible heritage. Yet, for me, the takeaway is so much more than simply the physical form. For me, studying a work of art allows me to see beyond the physical and into the metaphysical and the spiritual. In other words, it allows me to go from the tangible to the intangible.

COVER STORY

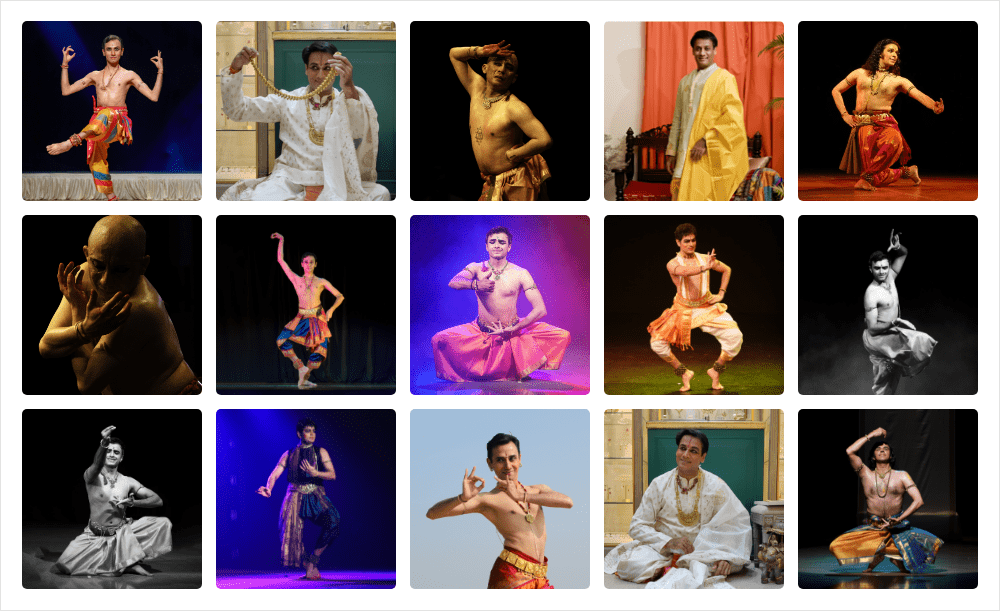

Privilege, possibilities and experiences… We reached out to six Bharatanatyam male artistes from across the globe and asked them a common set of questions to feel enriched with a plethora of ideas and insights on inclusivity, gender-neutrality, exploration and experimentation, research and expression and about the beauty of art and how it enables the artiste to be vulnerable in a world so frail and chaotoic We asked a few male dancers their opinion on privilege, exploration and takeaways in the field of Bharatanatyam for them. We are very happy to share their take with you all. Read on to know more. Mavin KhooBharatanatyam Artiste The greatest privilege of being a male dancer in the world of Bharatanatyam and the most crucial takeaway from it? I think for me personally, I have always been resistant to the underpinning of gendered roles in dance. So to equate notions of being male, alongside the privileges it may bring, is slightly problematic. The defining of the male dancer brings with it so many layers that I have never felt comfortable with – prescribed notions of masculinity or even worse, hyper heterosexual masculinity. In all the performative elements required to justify the gendered role, I have always asked, where is the dance? A quick reflection of my Guru Lakshman Sir – I was performing Shringara-based Varnams in the early 90’s when male dancers were expected to dance only bhakti based works. In one performance, a senior guru approached Sir and questioned him for allowing me, as a male dancer, to dance Manavi Chekona in Sankarabharanam. Sir’s reply was, ’I don’t want him to dance like a man, I want him to Dance!’ As a male dancer have the possibilities of exploring the world of Bharatanatyam been liberating or limiting? I have always felt that the identification of being a male dancer would be limiting to my growth and development as an artiste. The body is the strongest, visible construction on stage that reads numerous things. I wish to only Dance as a presence and energy force that is man, woman, neither, both. That is where I feel, a kind of liberation occurs; when I can be everything and nothing. Your favourite character or piece from your repertoire that is closest to your heart, and why? I guess Radha is a state of being that I am most familiar with. Firstly, because we are all Radha and she sits within us a spirit that is so human in her desires, her needs, her flaws. Secondly, I specifically refer to her as a state and not as a character because she is not a performed role- instead of playing Radha I try to reveal the Radha in me. Radha is Mavin, and Mavin is Radha. It is the best way that I can find the truth in ‘our’ voice.—————— Mohanapriyan ThavarajahBharatanatyam Artiste The greatest privilege of being a male dancer in the world of Bharatanatyam and the most crucial takeaway from it? Firstly the greatest privilege of being a Bharatanatyam male dancer is to have received immense encouragement and refined training so far, in my dance journey. When I left home to go to India,in my early teens, to live by myself, to chase my dance dream, I realised how privileged I am to be able to be supported by my parents and pursue what I love. Today when my audience appreciates my art, I realise how privileged I am, to be able to be taught and guided selflessly by my teachers and mentors. It is that love for dance that has never let me look back, as I started to discover more and more in the world of Bharatanatyam. I feel my bond with Bharatanatyam became stronger and a larger part of my life, helping to develop a distinct personality, who I am today. I always wanted to accumulate and imbibe deeper knowledge not just in dance, but everything that is connected to dance. My crucial takeaway is to have trust in everything I do, learn to appreciate what I see, be grateful for what I have and not take advantage of my body but to care for it at its best, so that I have a smooth run in my career. As a male dancer, have the possibilities to explore the world of Bharatanatyam been liberating or limiting? It is a notion that male dancers have limited sources because mostly Bharatanatyam compositions are based on Sringara rasa, but for me as a male Bharatanatyam dancer, exploring sources for Bharatanatyam is definitely liberating. I have come across beautiful compositions from the vocal concerts by great artists, explaining their origin and beauty. This has inspired me to create a lot of dance compositions. I have delved into many interesting compositions of Nayanmar from the seventh century Bhakti movement and the outcome of these research has resulted in some of the best compositions to be brought on stage, which are not known to many. Literature is another gem of sources that allows dancers to explore human emotions which is common for all of us. Modern day poets have different approaches in their composition and that is something to consider. After all it is one’s creativity and ability to be able to give life to a composition, with the right intent and conviction, so that it can be as enjoyable to spectators as well for the dancer. In my approach, I study a composition thoroughly, right from the lyrics to the subjective nuances, like intention of the words and meaning, the stories, the situations and the composer’s approach. This thorough study allows me to give perspectives, when I want to choreograph and perform it for my audiences. Interestingly this process has led me to discover lesser known contents from what we have in the form of texts. Your favourite character or piece from your repertoire that is closest to your heart, and Why? I love the compositions which have a sense of wittiness (Hasya rasa) like Nindastuti. I

Cover Story

Dance of the Camera What happens when dance is on film? Do things shift for the artiste and choreographer when they are being seen through the camera’s eye? How do they negotiate this medium to create a work-of-art that is authentic to the dance and to cinema? Three senior Bharatanatyam artitses – Aravinth Kumarasamy, Priyadarsini Govind and Rama Vaidyanathan, reflect upon their dance on film projects and share insights… Read on Rama Vaidyanathan Bharatanatyam Exponent What was the premise of your dance on film, Sannidhanam? Sannidhanam found its birth during the lockdown years; all stage concerts were cancelled. Six of my students were in Delhi cooped up in a hostel. I wanted to engage them meaningfully and also wanted to do something interesting that would make the best use of the situation that we were in. So, when Jai Govinda, dancer-choreographer-curator based in Canada, asked me to present a new work for his online festival, I decided to work on an ensemble production that catered specifically to the camera. What were the significant shifts that you had to make in terms of your dance and the way you imagined dance on screen? Could you share a few examples? The most important thing was the content of the performance, it had to be something which the camera could enhance. I decided to do something on the concept of sacred geometry – the triangle, square and circle – which could be shown dramatically through the camera. Ideally, I would not have chosen this for a proscenium stage. Do you think dance on film has the potential in reaching larger audiences or do you think dance on film was more an intermittent solution to a world that had come to a stand-still where dance did not find expression in the proscenium format. I think dance on film began as a solution to the absence of stage concerts during the pandemic. But in the process, dancers have gone on to realise its potential and have started experimenting with the medium. The possibilities of exploring it artistically as well as the avenues it created for newer and larger audiences was quite overwhelming. I think it has definitely added one more dimension to showcasing dance and is here to stay. What were some of your key learnings by virtue of creating and being part of this dance-on-film? I learnt a lot about camera angles, editing and engaging special lights for the camera. Learning about a different perspective to dance was interesting as well as challenging.——————— Priyadarsini Govind Bharatanatyam Artiste What was the premise of your dance on film, Yavanika? The purpose was to showcase the compositions through the medium of camera. For all of us as artistes, filmmakers and dancers, the potential of movement and especially this kind of trained movements, the variety of our compositions and the depth of abhinaya has to be documented and filmed on for posterity. Dance on film has incredible potential. To me, this is just the beginning. What were the significant shifts that you had to make in terms of your dance and the way you imagined dance on screen? Could you share a few examples? The important thing that I kept in mind was that the production was not seen by an audience seated in front of a proscenium stage.The eye of the camera could travel anywhere. It could take you and direct your gaze to where you want for the audience to see. It could be a small movement of the hand or a formation or the angle at which you want the audience to see the formation or just the pace of the movement of the camera or the details that the camera notes. That was really exciting. Do you think dance on film has the potential in reaching larger audiences or do you think dance on film was more an intermittent solution to a world that had come to a stand-still where dance did not find expression in the proscenium format. I think it has incredible potential and is definitely not a stop-gap solution. What triggered the production was not just documentation. Rather, the camera was another element or a collaborator in the project. That was extremely important. The camera was doing the work of both the dancer and the audience. It was directing the gaze of the audience and registering the movement in a creative and aesthetic way. What were some of your key learnings by virtue of creating and being part of this dance on film? I think the entire working process was a huge learning for me. Our director, Sruti Harihara Subramanian would come in everyday and for the last ten days, Viraj Sinh Gohil the cinematographer and Sruti’s assistant Shiva Krish, the Associate Director would also be there to watch our rehearsals. So the involvement of the director and entire team was 100%. We would demonstrate and Sruti would question and I would do the required changes. Sruti had to divide the shoots, put them on paper, as we were shooting seven compositions in two days and that was not a joke. So everything had to be done like a script to the last detail. I made changes that came out of our discussion till the last four or five days. When you know you are not dancing to the audience but rather to the camera, your mindset also shifts. The possibilities of the formations, what one would want to emphasize on, everything opens up. Right from the start, we were in tune with the idea that this was a dance on film and not a presentation seen on stage.—————– Aravinth Kumaraswamy Artistic Director, Apsaras Arts, Singapore What was the premise of your dance on films? How different were the two from each other? Both these films, Sita and Amara were filmed as CGI films in green screen studios. I believe they were the very first such CGI films featuring Bharatanatyam performance when they were made in 2020. SITA brings to

COVER STORY

Master Weaver of Magic Raising a toast to Aravinth Kumarasamy, Artistic Director of Apsaras Arts, as he receives one of the most prestigious accolades for arts practitioners in Singapore – the Cultural Medallion… In the first week of December, Apsaras Arts Artistic Director Aravinth Kumarasamy, the man who needs no introduction to the Indian performing arts world, who wears many hats, multi-talented and multi-tasker, who believes god is in the detail and whose singular commitment to dance and to the world of the arts has resulted in a collective upliftment of the creation, production and expression of the arts in terms of ideas, innovation, form, expression – raising the creative bar of dance across the world – was conferred Singapore’s prestigious Cultural Medallion for 2022 in a stately ceremony held at the Istana, the official residence of the President of Singapore. From a recognition perspective, the Cultural Medallion – instituted in 1979 to recognise individuals whose artistic excellence, contribution and commitment to the arts has enriched and distinguished Singapore’s arts and cultural landscape – is unarguably the pinnacle accolade for arts practitioners in Singapore. What makes receiving this award just extra special is the fact that more than 30 years ago, Apsaras Arts’ co-founder Smt Neila Sathyalingam, hailing from Sri Lanka, was conferred the same honour. Neila Maami, as she was fondly known in the world of the arts, continues to be celebrated for her commitment to building Apsaras into a premier dance academy for classical Indian dance form Bharatanatyam, for cross-cultural works with Chinese and Malay dance forms and for showcasing Singapore’s multicultural personality around the world. Hailing from Sri Lanka, in 1987, as a 21-year-old, Aravinth came to Singapore to pursue his dreams. Two decades later, Aravinth was hand-picked by Neila Maami to carry forward the rich legacy of Apsaras Arts that she had so fondly built. At that time, Aravinth was neck deep in the corporate world – managing a tech start-up with international employees across 15 countries. Aravinth took a massive pay cut and committed himself to the arts, to further realise Neila Maami’s vision. For over three decades now, Aravinth has creatively, with a sense of commitment and conviction, envisaged and nurtured this art form with his imagination and ingenuity. His artistic philosophy stems from his pursuit to enable the Indian classical dance form Bharatanatyam, predominantly a solo art form, to transform into a fine and compelling ensemble-centric expression. His dream and desire to create, nourish and nurture a repertory company, a one-of-its-kind in Singapore and arguably across the world, in the space of Bharatanatyam. As a Singapore brand for Indian classical dance ensemble work, inspired by South East Asian narratives, raises a toast to the potential and the possibilities of Bharatanatyam, presented at international festivals and venues, flying the Singapore flag high. Much like the eclectic nature of his creations – to date, he has created and directed more than 35 original productions – that are diverse in form and content, Aravinth is a storehouse of many identities that inspire and influence each other. As an artiste par excellence himself, he is conscious of tradition but also cognizant of the dynamics of a rapidly changing global dynamics, where innovation and technology have vital roles to play. During the pandemic, Aravinth imagined and produced two digital CGI based one-of-a-kind dance films – SITA and AMARA – that pushed the creative envelope and have pioneered a way for a new possibility for the world of dance in exploring the digital space. Apsaras Arts’ latest production is Arisi: Rice that premiered in December at the Esplanade in Singapore, this mammoth production – stunningly visual – is an ode to rice, and in terms of expression, is collaborative in form and spirit. Featuring traditional Balinese dancers and Singapore Chinese Orchestra musicians alongside Bharatanatyam dancers and Carnatic musicians, the work is a visual documentary on the history, heritage and narratives of rice and its traditions from across the world. With a 360 degree vision for brand Apsaras Arts, Aravinth has championed industry development, and successfully curated and convened Indian Performing Arts Convention (IPAC) annually in Singapore since 2012 and in Australia since 2021. He is the proud recipient of several awards including Singapore’s “Young Artiste Award” by NAC (1999), “Bharata Kala Mani” (Apsaras Arts 2000), “Aryabhata” (India 2016), MCCY Award (2017), “Kala Ratna” (Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society 2019), “Natya Kala Upasana” (Bhaskar’s Arts Academy 2019) to list a few. Under his leadership, Apsaras Arts is possibly the most internationally travelled dance company in Singapore, regularly touring and presenting sell-out shows of original works in France, the UK, Australia, Malaysia, India and Sri Lanka. Apsaras Arts dancers and musicians have toured to more than 40 countries, collaborating with leading dance companies, legendary dancers, choreographers, composers and presenters from the international Indian dance fraternity. “I have been blessed to work with many young creative minds at Apsaras Arts, and this recognition will inspire our team to strive towards our vision for excellence. I hope our collaborators, partners and audiences will support this younger generation of Singaporean artists to pursue their passion in the arts, making Singapore stand proud on the global stage,” says Aravinth. Aravinth Kumaraswamy also received the Kala Seva Bharathi award from Bharat Kalachar as part of their 34th Margazhi Mahotsav. This award was conferred to him on December 16, 2022 in Chennai, along with other artistes like Vani Jairam, Embar Kannan and Revathi Ramachandran.

COVER STORY

Into the Music of Dance Our Cover story this edition features three musicians and music composers for dance from India, who share their experiences of making music for dance SUDHA RAGHURAMAN Carnatic Vocalist, Composer and Music Arranger What is that characteristic aspect that differentiates composing music for dance and composing music in general? Composing music in general can be like tuning a particular song or putting swaras together or creating score for background music. It doesn’t need too many ideas. Simplicity is its charm. But when we compose for dance, we get into details like the meaning of every word, the underlying meaning, the multiple layers of meanings, and also check if the composition is suitable to dance as an entire piece. While composing swaras for dance, it has to be adavu-compatible. Swaras need not be very mathematical and complex. Sometimes, mere raga lakshana swarams can convey the mood so much better than very skilled or technique- oriented swarams. Sometimes, the situation demands the swaras need more maths. That’s when we use complex patterns. There’s a great level of detailing that goes into composing for dance. I personally feel that a singer or composer must know the meaning of every word/ line, the sthayi bhava of the particular poem/sahitya to be able to create something very beautiful and unique. The audience should be able to listen to the music and relate to the theme of what the dancer intends to portray. One should be able to grasp the theme by listening to the music, with closed eyes. To achieve that requires a lot of hard work. It doesn’t happen in a day. The music of dance should also be able to exist as standalone. Even if one were to listen to it without watching the dance, they must be able to grasp it and create their own dance with it. By virtue of being a musician for dance, what is your relationship with dance and the dancer? Having worked in the field of dance with senior dancers and this generation of dancers for three decades now, I have learnt that every dancer is unique, every dancer has their own strengths and shortcomings and every musician too has their own share of shortcomings. If we could work on our strengths and create meaningful pieces of art, I’d say we are doing something right. Every time a musician sings for a particular dancer, the musician should sound like that dancer. The music must dance and the dance should sing. I think this is crucial; the two are inseparable. When I sing for dance, I become one with the dancer in a performance. There can be no other distraction other than the music, dance, bhava and melody. This is the synergy that is created. To me, every dance programme that I sing for is as much my own programme – never to supersede the main artiste, but to be completely involved in the performance. Many a time, the dancer may not fix the repetitions. So one has to be super alert and spontaneously respond to the dance. The dance and the dancer should be with the musician. For me, I become the dancer, a co-performer and I recognise the dancer is the main performer. Every dancer has a signature style of their own. Do you keep that in mind when you begin composing? What is your process like? Certainly. If I compose music for dance, the composition should sound like it reflects their dance. Their signature style in dance should reflect in the music. I have a particular practice to let go of the classic Sudha style while singing for dancers. Only after working for hundreds of kutcheris, did I realise my strengths and weaknesses. What matters is also chemistry; it is important to have a good relationship with the dancer you are working with to be able to produce good music. Any small differences will show up on stage and in the composition. Over the years of composing and performing music for dance, how have you evolved as a creative artiste? I have certainly evolved over the years. But that has come from years of singing and learning from my mistakes. I was barely 20, when Leela (Samson) Akka called me one morning and asked me to sing for a programme that very evening. We had only one rehearsal soon after that phone call and I went on stage. At that point, my focus was only on singing what we’d rehearsed right more than taking my music or the dance to the next level. Today, I have evolved so much as a dance-musician because of the efforts of the dancers I have worked with and my own interest to understand the concepts and themes I work with meticulously. I follow up what I do with more research and create for myself a vision of my own. I have been very fortunate to be associated with wonderful artistes from all over the world. They give me the freedom of imagination to pursue and evolve with my own craft. Can you – from your repertoire – share with us one project that has been challenging and invigorating at the same time? Moving Boundaries by Rama was a challenging project. The lyrics were minimal lyrics and there were three different pieces of various genres on the topic of bliss. It was not easy working on this, especially in the middle of the pandemic when people’s mental health was at an all-time low. But that also helped me to create something very unique. With minimal lyrics and three stories for 45 minutes, I just used the grammar and manodharma, to create music for this project. Working on Shakunthalam has helped me appreciate Sanskrit more and it has now become my favourite language. Kashi by Meera Balasubramianm was composed without the dancer working with me, in-person. Purushotama for Aravinth choreographed by Rama Vaidyanathan and Pratidhvani for Geeta (Chandran) ji also was created on echo. There have

Cover Story

Three costume designers Lakshmi Srinath, Sandhya Raman and Mohanapriyan Thavarajah from Chennai, Delhi and Singapore respectively, share their process, insights and views on designing and creating costume for dance and dancers Lakshmi Srinath “My interest in costume grew organically as a result of my passion and career as a visual artist” “My interest in costume design was organic as a result of me being a visual artist. I had a children’s boutique for about ten years and I started making personalized clothes for people. This went on for a long time. One of my customers, Uma Ganesan from Cleveland, an arts patron and curator, wanted me to design the costume for her upcoming dance production. I protested initially but then she insisted that she liked my vision, aesthetics and the way I put things together. She placed her trust on me and was the one who started off this spark in me. It was a tremendous effort but it went off very well. I created costumes for her production, Silappadikaram and that was my foray into costume for theatre and dance. I used to design theatre costumes for The Madras Players back in the day but in the context of dance, this was my first experience. I am eternally grateful to Uma because she opened up an entire new creativity in me.” “Priyadarsini Govind was ready to experiment and gave me full freedom with design” “After designing costumes for Uma Ganesan’s production in 2004, I did a few designs for Bharatanatyam exponent Meenakshi Chittaranjan. Then of course, with Bharatanatyam exponent, Priyadarsini Govind, I’ve had a long-standing association. Priya was ready to experiment and give me complete freedom but at the same time I had to keep in mind the requirements/ requisites needed for concerts at venues like the Music Academy and so on. I was also not unconventional in thought and it worked for her too. She is a great person to work with. I also did the costume for the theatre production Angkor in Singapore, in which Priya played the lead role and she requested Aravinth Kumarasamy for me to create her and Anjana (Anand)’s costume. I was very happy to do this and it was an amazing experience.” “The wearer of the costume is the most important” “Priyadarsini Govind used to experiment quite a bit and I introduced different kinds of fabrics apart from the traditional Kanjeevaram silks, which most of the dancers tend to use. We tried different textures and she was very happy to experiment. So it definitely depends on the person! I have also done lots of clothes for singer TM Krishna as well. He gave me complete freedom and asked me to do what I want. He was open to trying different colours and was flamboyant, which actually goes well with his personality. I work best if I am given a long rope.” “The stage is like a canvas and it is important that the balance is maintained” “It is not a different hat but there are different aspects with which I approach the work. When there are four or six dancers on stage, the look of each dancer has to complement each other. It also depends on the characters they play and for me, the most important thing is the colour. Usually when I see a stage, the balance has to be perfect because it can’t be a lop-sided vision. So it is very important for me that I approach it with a sense of colour. Colours have to synchronize so well that one person cannot look heavier visually than the other. I also found from experience that colour blocking was most effective on stage. I find the tiny prints that look very pretty appear as a huge mass on stage and I learnt not to use them. The stage is like a canvas and it is important that the balance is maintained.” “People do say that they see me in my designs” “India is resplendent with weaves and different kinds of textures. Since I am an artist, my work has a lot of textures in it. So my eye automatically goes towards textures. I love handlooms, anything done by hand and the imperfections in it. Textiles also fascinate me a lot and this work has given me an opportunity to work with textiles from an artist’s perspective. It has been a great experience! I don’t know if I have a signature style. All I know is it has to look perfect in my eyes. I am not sure if that is my style. But people do say that they see me in my designs. I just work from my heart!” “The storyline is very important in important for me in the context of design” “I always insist on the brief to be clear so that I have an idea on what I am supposed to do. Then I share my thoughts with the producer and when we are in sync, I come up with the sketches. The fabric is very important while designing. When a character walks in with a few other characters already in the background, it all has to synchronize beautifully. So I first pen down the colors out and then check their availability in stores. Then I try to synchronize with what is available and come up with a scheme. The designs are fairly standard. For costume, it is important to keep in mind that it should be easy to dance in, easy to change into and fabrics that can be maintained easily without much ironing. Because, most dancers travel a lot and do multiple shows and it gets difficult to iron or steam out the costumes for every show. So it has to be practical. So basically the costumes need to have visual beauty, a structure which is easy to dance in and fabrics which are easy to manage- packing and carrying around. Also, there is jewellery too which needs to be in sync. It is important