A Dance anthropologist’s perspective of “Agathi I Refugee”

By Katherine C. Zubko, University of North Carolina Asheville “How does Agathi add to the history of performing on social themes? Let’s take a closer look at a few segments within one of the most poignant scenes in Agathi, a group dance production rendered in bharatanatyam I will refer to as the ‘boat scene.’ This boat scene is both rooted in recognizable bharatanatyam frameworks, as well as utilizes that familiarity to provide a bridge to expanding attention to difficult human experiences not typically seen in the dance form. The ‘potential of the arts to move our hearts and not just our minds,’ as one London audience member noted, allows Agathi to work towards defeating the asuras of apathy when it comes to this ongoing global refugee crisis. Read more on what Katherine C Zubko says about Agathi I Refugee experience. Bharatanatyam dancers spend most of their stage time inhabiting the movements of Hindu gods and their devotees, attending to the emotional subtleties of devotional relationships, as well as their powers of intervention. At any given moment, the focus may be on Yashoda’s affection for the often mischievous Krishna as a child or his later turbulent love relationship with Radha, while the next may reenact Shiva’s powerful cosmic tandava dance of creation and destruction, Durga’s heroic intervention in killing the buffalo demon, or Vishnu taking the form of any of his avatars to restore dharma, or righteousness to the world, all acts that demonstrate godly investment in cycles of worldly and human well being. The range of emotions is intended to reflect human and divine experience in depth. While bharatnatyam dancers have explored many other narrative and thematic threads outside of Hindu mythology, very few have employed the underlying techniques of movement, rhythm and rasa to the very contemporary realities of immigration and refugee experiences with performative and aesthetic integrity. During this past 2017-18 dance festival season in Chennai, Apsaras Arts’ production of Agathi: The Plight of the Refugees, caught my attention precisely because of its cutting edge contemporary topic performed during one of the most traditional, classical arts festivals, but also its efficacious use of ensemble choreography to deliver a powerful social message. As a dance anthropologist and scholar of bharatanatyam, I am particularly interested in what is created and experienced by dancers and audiences when embodied gestures and emotion transfers into unexpected contexts. What embodied expectations and resonances frame the possibilities for creative engagement, where do adaptations occur, how successful are they, and what effects does this have on the dynamic, evolving dance form and the dancers that embody it. My current quest examines how bharatanatyam dancers choreograph and perform on contemporary social issues, and Agathi will be the focus of one of the chapters of the book. Productions on social issues are nothing new within the history of dancers trained in the classical style of bharatanatyam. Mrnalini Sarabhai and her daughter Mallika, Chandralekha, Anita Ratnam, and Ananya Chatterjea have classical training, but each shifted into more multimedia, mixed-form or contemporary iterations of their own designs related to the treatment and experiences of women, environmental devastation and other topics. Other dancers have stuck closer to their classical techniques, including foundational mythological references as part of social commentary, such as Malavika Sarukkai’s production on Ganga, Leela Samson’s Nadi, and the Narasimhacharis’ Karuna Shakti. While artists engage in different levels of artistic license and activist commitments, the underlying reasons for such endeavors range from affirmations of the educational purpose of dance by the god Brahma found within the Natyasastra (1:108-116) to dancers’ feminist, social or ecological concerns. How does Agathi add to this history of performing on social themes? Let’s take a closer look at a few segments within one of the most poignant scenes in Agathi, a group dance production mostly rendered in bharatanatyam I will refer to as the “boat scene.” After performing a handful of vignettes that provide a window into some of the reasons people flee their homelands, from earthquakes and tsunamis, to fires and political violence, the stage goes dark except for a central spotlight. The urgent rhythm of the dancers’ feet underlie each individual emerging into the spotlight, depicting some component of fear in their lives, whether it is witnessing the horrors of human tragedy to others or being subject to harassment themselves. As the group comes together communally in a single line, they begin to call out for help, waving their hands, while also shielding themselves to the onslaught. There is a constant rhythm and rocking motion to this choreography, imitating the instability of the ground under their feet due to their circumstances, and foreshadowing the rocking of the boat they now call out to with their hands. Jumping into the boat one by one, the dancers hold onto the sides, some feeling sick, others crossing their arms over themselves with wide-open eyes, and one mother holding a baby trying to steady herself and anxiously trying to calm the child. All but the mother rise and clasp hands, morphing into the oblong shape of the boat surrounding the mother and child. Rocking, leaning, tilting high on one side and then the other, the people-boat navigates the rough waters. Hands unclasped, the boat turns back into individual people, being tossed around as the dancers roll into each other on the ground, eventually showing distinct moments of sickness, fear and anxiety. As I want to refrain from giving away the climactic moments of this scene, let me stop this description and discuss some analytical points. Without any lyrics, the experience of the refugees relies on mood, rhythm and embodied storytelling. First, the use of rhythm produced communally, in the midst of individual experiences of terrified people, points to a more universalized problem – while each refugee is experiencing their particular context, the tragedy is a more globalized human problem. Accompanying this intense thisra (3 beat) rhythm, is a second focus point created through the facial expressions, gestures and postures that evoke the rasa, or aesthetic mood,

Travel memories from the ASEAN India Youth Summit at Guwahati, India

By Soo Mei Fei As Mei Fei recalls her experience at the ASEAN Youth Summit 2019 held at India, two years on, she finds herself still pondering about dance as the bridge that connects. “It is never an ending point, but a starting point that branches out to various paths. It is a journey that is simultaneously unique, and yet in some sense, universal.” I rushed home from my Odissi performance at the Artwalk Little India festival, grabbed my luggage, and headed off to the airport! That was how my trip to the ASEAN- India Youth Summit in Guwahati, Assam began from 3rd to the 7th of February in 2019. On this trip, I was accompanied by 8 other delegates from various walks of life – youth who were studying and working in various sectors in Singapore. I remember thinking to myself: what does a dancer do in a conference like this? What is the role of dance (or any art form), when considering global connectivity, diplomatic relations, economics, and all the other areas of life that seemed (to me, at that time) so far removed from art? I found my answer during this trip: 2 simple words – art connects. Art is the bridge between two: two strangers, two generations, two cultures, two countries, and the list goes on. My introverted self struggled to find a way to connect with others at the conference, yet when I introduced myself as a dancer, I quickly found myself in conversations about dance – memories, experiences, and a wonderful exchange around dance. And I wondered about the role of Bharatanatyam – which is still heavily seen as a “traditional” “ethnic” art form to the majority in Singapore, and finding less support than art forms that are considered “contemporary”. I raised the question at a panel discussion: how do we ensure that “traditional” art forms continue to grow and prosper, in the world today? Ambassador Pham Sanh Chau very eloquently put it across: preserving an art form and viewership are two different things. It was such a simple idea but to me it felt like a huge paradigm shift. In passing on an art from one generation to the next, we build bridges that give access, and open new pathways. Two years on, I find myself still pondering about dance as the bridge that connects. It is never an ending point, but a starting point that branches out to various paths. It is a journey that is simultaneously unique, and yet in some sense, universal.

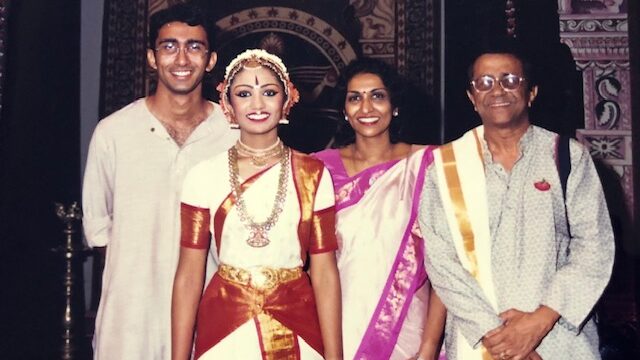

A conversation with Devapriya Appan, Senior Company Dancer

By Vidhya Nair “There are no formulas. When we don’t have time, we need to make time. Prioritise. Rearrange. Dance was something I wanted to do for a long time, then I realised that I need it to remain balanced. It’s an important part of having balance, a means to find happiness.” Read more about Devapriya, Senior Company Dancer who is performing in Agathi I Refugee this April on her dance journey. VN: Introduce yourself to us Priya. Tell us a little about your background. DP: I’m a Singaporean Indian, 2nd-3rd generation. My mother’s parents had emigrated from Malaysia. My father was born in Malaysia but returned to India during the Japanese Occupation. He returned to Singapore to work after he completed his Engineering studies in the 1960s. My father till his retirement was a university lecturer in Singapore and my mother is a doctor in private practice. I grew up with my elder brother. I had studied medicine in Melbourne and was interested in working with children and adolescents so was initially posted to Singapore General Hospital and KK Women’s’ & Children’s’ Hospital in paediatrics before I moved to specialising in psychiatry at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) where I’m based now. My husband is a doctor and we have two sons aged 7 and 3. VN: How did you get introduced to Bharatanatyam? DP: I joined Apsaras Arts at the age of 6 years at Cairnhill Community Centre under Mohana Harendren (Neila Mami’s eldest daughter). My parents were keen for me to learn as my mother had learned the Veena as a child and many in my father’s family had learned Carnatic music. I recall speaking only Tamil till the age of 4 at home. As a student at Swiss Cottage Primary, after school either my parents or brother would take me for classes. Classes were a lot of fun. I attended many birthday parties and many of the girls I met in dance class continued to be friends even in my secondary school at Raffles Girls (RGS). I was part of “Little Angles “– a children’s’ multi-ethnic dance troupe created by Neila Mami, Mdm Som Said and Mdm Yan Choong Lian in the early 1990s. [ This was an offshoot inspired by the National Dance Company which had closed down in 1985 due to lack of funds]. In 1995, when I was in Primary 5, I travelled to Paris with the troupe and we all had to learn elements of Malay & Chinese dance along Bharatanatyam and we performed there. It was during school term time but my parents allowed me to participate. This was the first time I got to be trained by Mami. Back then, Mami was the feared one, the one taking our exams. Her demeanour seemed scary and imposing. She had a strict persona. During the Paris trip, my fear dissipated as she was very engaging and protective. By Secondary 1, I started to take individual classes with Mohana akka in preparation for my Arangetram. Mami taught me personally several items of my repertoire – the Pushpanjali, Varnam and the Kirtanams. It was an eye-opening experience. My arangetram took place on 3 July 1999 at Jubilee Hall, Raffles Hotel. I was 15. It was an exciting night for me and I also sang part of my kritanam, ‘Kurai ondrum illai’. The few months leading up to the event was exhilarating and stressful. My parents were worried when they saw that I had lost so much weight and was coping with pains from physical injuries and it was quite daunting, managing school and dancing to live music to an audience. My fondest memories of that time were the evening practice sessions at Mami’s house on Meiyappan Chettiar road. It felt like a Gurukulam. Like I was living there too – spending lots of time with both Mama and Mami who would insist I have my meals there. It made me feel independent and consider dance as a serious pursuit. VN:What was your relationship like with Neila Mami? DP: I was one of the few medical students learning dance with her. Her students each had their individual relationship with her but I would get all the medical questions. Sometimes you wouldn’t understand in which context she asked her questions. She would say, “Why da? Why does this person have this sickness?” She liked asking me for medical advice and would be playful when I was watching over her food habits remarking to others, “She won’t let me take it, da… She’s very strict!” She was supportive of my decision to be a doctor. I remember being introduced to famed dancer Dr Padma Subramanyam in India as a medical student. She was mostly concerned about me continuing to dance. She was not one to meddle in your choices. I recall asking her why she was not encouraging another student also in medicine to not discontinue and she said, “No da, she’s different. I know you will continue.” She had the ability to allow you to learn from others and often made the learning happen. She helped me organise lessons while I was studying in Melbourne. I learned from Chandrabanu in Melbourne and later in India where I also did a year of research, I learned from a teacher in Vellore and spent a month in Bangalore learning from Kiran Subramanyam & Sandhya Kiran. The teaching there was very different. I learned many new aspects of choreography, listened to new music. When I returned, I had to show to Mami what I had learnt and taught it to others (e.g., the Thillana I learned in Bangalore was taught to my peer, Loga who performed it for her arangetram). Mami also challenged me, often giving me more than I would think I’m capable of. Three months after I had my older son, Mami cast me in a production and was confident that I could do it. I would prefer group ensemble work but she would encourage me to take up main character roles and do

Dance Events-March 2021

March 2021 “Here is a digest of digital and on-stage live events that Apsaras Arts team participated in March. From celebration of Mahashivaratri by the Fine Arts Society of Chembur at India to the celebration by local dance group, Shere Punjab Bhangra Singapore, it is a pleasure to collaborate with art groups beyond borders and cultures.” On March 11th in celebration of Mahashivaratri, the Fine Arts Society of Chembur organized NRITHYOTSAVAM -2021 featuring unique presentations by accomplished artists, namely Padma Bhushan awardees Sri. Dhananjayan & Smt. Shanta Dhananjayan; Kalaimamani awardees Lavanya Sankar, Anil Srinivasan, Sikkil Gurucharan, Parswanath Upadhaye and Mohanapriyan Thavarajah, resident choreographer and principal dancer from Apsaras Arts, Singapore. Mohanapriyan opened the performance with an Alaripu on Raag Charukesi. He presented the celebrated Shiva Panchakshara Stotram composed by Adi Shankaracharya, followed by a Ninda Stuti composed by Papasanasam Mudaliyar, choreographed by Mohanapriyan Thavarajah. Watch the performance here: https://youtu.be/sbgTRbpGevw On March 7th Shere Punjab Bhangra, one of the celebrated local Bhangra dance troupes marked their re-entry back to live stage since the onset of pandemic at the Esplanade Recital Studio staging the SPB Showcase Day 2021. ETHOS Odissi dancers from Apsaras Arts Academy were invited to open the showcase with a traditional choreography by Soumee De named Pallavi (that means elaboration) and performed by her students Rohita Rangu, Lekshmi Syam and Srividhya Gopalan. This opening was followed by two powerful performances by the budding dancers groomed at the SPB academy.

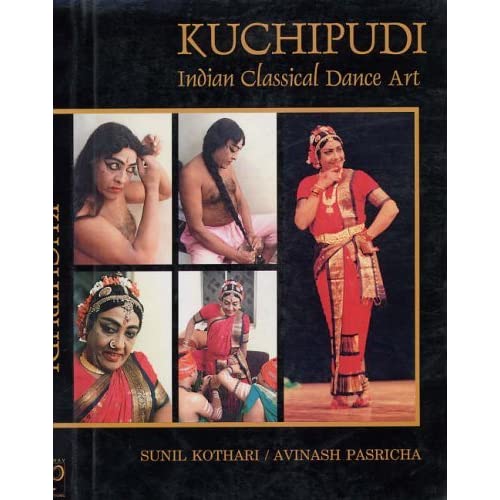

Kuchipudi Indian Classical Dance Art

By Sunil Kothari and Avinash Pasricha One of the seven major classical dance forms of India, Kuchipudi in its solo avatara has acquired a status of a classical dance form of Andhra Pradesh. The story of Kuchipudi from its origin as a dance-drama and its emergence as a solo dance form is one of the most fascinating phenomena engaging attention of the gurus, the performing dancers and the research scholars. Essentially a preserve of the male dancers, who also excelled in the female roles, today Kuchipudi is being mainly performed by the female dancers. However, the tradition continues to survive in Kuchipudi village, some 30 kilometres away from Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh. The traditional dance-dramas continue to exist along with more popular solo dance form. Kuchipudi has innumerable votaries not only in India but also abroad and their number is ever increasing. Padma Shri Dr. Sunil Kothari, dance historian, scholar and critic, traces in this volume the origins of the dance-drama tradition, correlating the prayoga, the practice and the shastra, the theory and how from the natya, the drama, its integral elements nritya, expressional dance and nritta, the pure dance in the hands of creative, traditional gurus have shaped its present solo format, giving it its own identity. Based on his extensive field work Dr. Kothari has studied the allied forms like Vithi Bhagavatam, Turpubani Vidhi Natakam, Pagati Vesham, Navajanardana Parijatam, Bhagavata Mela Nataka, Kuravanji dancedrama and offered an overview of the dance form as it exists today and continues to develop in its many ramifications. He has also dwelt upon the all-pervading influence of Vempati Chinna Satyam and his contibution in shaping Kuchipudi into a solo form along with the dance-dramas that he has choreographed. The brief biographies of the traditional gurus and some of the celebrated exponents add to the value of this volume, presenting the current state of Kuchipudi on the contemporary dance scene. Profusely illustrated with 166 colour and 221 black and white photographs by the ace photographer Avinash Pasricha and designed by the eminent artist and designer Dashrath Patel, Kuchipudi is a major significant study of the classical dance form of Andhra Pradesh. About the Authors Padma Shri Dr. Sunil Kothari Padma Shri Dr. Sunil Kothari is a renowned dance historian, scholar and critic. He received Ph.D. in ‘The dance-drama traditions of Kuchipudi, Bhagavata Mela Nataka and Kuravanji with special reference to the Rasa Theory’ from the Department of Dance, M.S. University of Baroda in 1977. He received D.Litt. in Dance in 1986 from Rabindra Bharati University, Calcutta for his work on ‘Dance Sculptures of Medieval Temples of North Gujarat with special reference to Sangitopanishad saroddhara’. He served as Uday Shankar Professor and Head of the Dance Department of Rabindra Bharati University, Calcutta from 1980 to 1995. Author of definitive works like Bharata Natyam, Odissi, Kathak and Chhau Dances of India, he has conducted extensive field work, visiting centres of traditional dance forms and has documented them in their manifold aspects for the past forty years, collecting sizeable material to form a nucleus for a dance archive. Dr. Kothari has been a member of the Executive Committee of International Dance Council (UNESCO), Paris; Asst. Secretary, Central Sangeet Natak Akademi (Dance); member, Advisory Committee, Indian Council for Cultural Relations and several other cultural organisations. For more than thirty-five years he has served as a dance critic for The Times of India group of publications. He is a foreign correspondent of Dance Magazine, New York. For his overall contribution to dance, he has received from the President of India the Central Sangeet Natak Akademi Award, Gujarat State Sangeet Natak Akademi Award and many other honours. Currently he is writing a book on ‘New Directions in Indian Dance’ for Marg Publications. He is based in Delhi.

Sakhi

By Seema Hari Kumar With the welcoming transition into phase 3 declared by Singapore government, the Darshana Series presented by Apsaras Arts made its return to the live stage after a year-long hiatus. Darshana was conceived as an intimate dance series providing soloists an opportunity to connect with their audience and experience ‘sahrdaya’ or ultimate unison between the artiste and rasika. This objective of the Darshana series came to fruition so poignantly with “Sakhi – a solo presentation by Meera Balasubramanian” on 20-21 Feb 2021 at the Stamford Arts Centre Black Box. Centred around the timeless theme of friendship, Sakhi dwelled on the important role a friend plays as a peer, mentor, guide, messenger and companion in one’s life. The Singapore government’s announcement to enter Phase-3 on 28 Dec 2020 sparked a ray of hope to artistes, arts groups and connoisseurs who have been starved of physical audiences and a live theatre experience the past year. With this transition, the Darshana Series presented by Apsaras Arts made its return to the live stage after a year-long hiatus. Darshana was conceived as an intimate dance series providing soloists an opportunity to connect with their audience and experience ‘sahrdaya’ or ultimate unison between the artiste and rasika. This important objective of the Darshana series came to fruition so poignantly with “Sakhi – a solo presentation by Meera Balasubramanian” on 20-21 Feb 2021 at the Stamford Arts Centre Black Box. The avid reception to the live show was evident when the intended Show on 20 Feb 2021 got sold out within days of tickets going live on sale, prompting a second seating the following day. This makes it the first Darshana performance to be staged over two days. The first Show was presided by Mr Rajan Krishnan, CEO of KTC Group and Chairman of the Hindu Advisory Board; and the second Show featured Ms Kuntha Chelvanathan, Global Procurement Capability Leader at Ernst & Young. Centred around the timeless theme of friendship, Sakhi dwelled on the important role a friend plays as a peer, mentor, guide, messenger and companion in one’s life. Meera’s choice of portraying the varying degree of congeniality between the nayika and her friend was apparent with the clever choice of performance items. Beginning with a message that a magical swan brings to Damayanthi, Meera depicted a heroine in anticipation in her opening sequence choreographed by Vikas Parayalil. In the centrepiece of her margam that evening, Meera performed the “Swamiyai Varacholadi” varnam, a classic composition by Sri Thendayathupani Pillai in raagam Purvikalyani. In this item, the heroine grows increasingly impatient about seeing her Lord Kumarasamy and implores her sakhi in a myriad of ways to bring Him to her. Choreographed by Smt Rama Vaidyanathan, the varnam showcased a multitude of sancharis that were interpreted so intelligently to entertain whilst breathing new life into this traditional treasure. Following the varnam, the audience were treated to another jewel from Swathi Thirunal’s compositions – “Kaminimani”, set to ragam Purva Kamodari. Choreographed by Smt Bragha Bessell, this padam is interlaced with the covet sakhi’s lies and the all-knowing nayika’s play-along act, best showcasing Meera’s strength in abhinaya. The evening concluded with a thillana in Bahudari composed by Dr Lavanya Balachandran with lyrics penned by Prof Raghuraman to aptly describe the friendship and intimate relationship the dancer had with her dance, ending the repertoire on a celebratory note. Meera’s choice of featuring four different choreographers’ works in one programme was commendable and reflected a broader reality of the friendship and collaboration that take place in the arts industry, one that was especially felt deeper during these pandemic times. Meera Balasubramanian was also conferred with the Neila Sathyalingam Memorial Endowment Award during the Remembering Neila Sathyalingam Festival on 7 Feb 2021.

Virtual Events

Catch the virtual events that Apsaras Arts team participated during the month of February. Celebrating Sri Lanka’s 73rd anniversary by the High Commission by featuring a segment of “Anjasa”; a live panel discussion by story-tellers on “Faith, Beauty, Love & Hope” by the Asian Civilisations Museum featuring Artistic Director, Aravinth Kumarasamy and a feature by Fab India insta live of our senior dancer and Kathak faculty, Shivangi Dake Robert. Read here High Commission of Sri Lanka in Singapore celebrated its 73rd Anniversary of Independence on 4TH February 2021 by hosting a virtual event featuring a segment from “Anjasa” – which highlighted the features and philosophy behind the Buddhist ruins of Wattadage in the ruins of Polonnaruwa of Sri Lanka. This program featured other cultural performances from Sri Lanka as well. Apsaras Arts appreciates this participation and recognition at this momentous event. Watch this commemorative event here : https://fb.watch/3_6Lr1KwpV/ Conversations: Everyone has a story to tell in conjunction with the exhibition “Faith, Beauty, Love & Hope” at Asian Civilisations Museum on 19th February 2021 featured Aravinth Kumarasamy in a panel of story tellers. Each had to tell their interpretation of stories based on an artefact featured in this exhibition. Aravinth spoke about two distinct Buddha statues from Myanmar & Cambodia and how the stories of the Buddha and the way his teachings have travelled and imbibed by other communities which inspired the concept behind “Anjasa” – a production by Apsaras Arts that follows significant Buddhist monuments around Asia. Watch the panel discussion here: https://fb.watch/3Z-uAQYyYk/ @FabIndiaofficial featured Shivangi Dake Roberts in an instalive event on 1 MARCH 2020 featuring two choreography pieces by Pt Birju Maharaja. The event was watched by over 4000 views and received many accolades. Watch the performance here: https://www.instagram.com/tv/CL1cU3oJHAR/?igshid=6r3hof9vgoa1

Remembering Rukmini Devi Arundale, whose contested reforms shaped modern-day Bharatanatyam

By Dr V.R Devika On Rukmini Devi Arundale’s 117th birth anniversary, it is perhaps time to re-evaluate the scathing remarks relentlessly brought against her and her contributions to the world of Indian classical dance, Bharatanatyam in particular. “The Devadasis and others who danced, whatever their customs, whatever the circumstances in which they lived, they were people with devotion, they were excellent artistes. Even today, they really are the people from whom we can get the best ideas in Bharatanatyam. I must pay my tribute to them.” — Rukmini Devi Arundale’s demonstration talk at the National Dance Seminar in Delhi, 1958. Revisiting this and several other such statements of Rukmini Devi Arundale (29 February 1904 – 24 February 1986) becomes essential as one re-reads the relentless remonstrations by scholars against her alleged “sin” of Bharatanatyam “revival”, along with its “re-vivication, re-population, re-construction, re-naming, re-situation, restoration,” as posited by Mathew Harp Allen in his “seminal” essay Re-writing the Script for South Indian Dance. While remembering Rukmini Devi on her 117th birth anniversary, one is also reminded of a survey done by some on her, Mahatma Gandhi and Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy. In this regard, the highly “educated” are guarded and give ambiguous replies on ideologies, while the working poor talk about how difficult and challenging it must have been for these pioneers to chart a completely new course, inspite of being in privileged circumstances that could have given them a comfortable life. Today, it is perhaps time to re-evaluate those scathing remarks relentlessly shot at Rukmini Devi Arundale. Amrit Srinivasan, in her essay Reform or Conformity, says that when Muthulakshmi Reddy’s bill of 1930 — that sought the abolition of temple dedications — finally came to be passed into law in 1947, it seemed to have been pushed through not so much to dole out death to the Tamil caste of professional temple dancers, as much as it was to approve and permit the birth of a new “elite” class of performers. She speculates that this happened because of the support from the Theosophical Society that Rukmini Devi — who, along with her husband were its members — received, and she learnt dance and established Kalakshetra, an institute that “had been set up to restore the ancient glory of India and to counter the western Christian morality and materialism”. However, it was not the Theosophical Society, but social activist and politician Periyar EV Ramasamy and the Justice Party of Madras who supported the Anti-dedication Bill of Muthulakshmi Reddy. Reddy, an insider, who knew what it was to grow up with the stigma accorded to her community, introduced and fought for the bill, empowered by her modern education and position, with a trajectory akin to that of BR Ambedkar’s. In fact, there were many members of the Theosophical Society who had objected to the establishment of Kalakshetra in the Society’s vast campus. By 1947, Kalakshetra was a fully functional institute in the Theosophical Society campus with Mylapore Gowri Ammal, the last Devadasi of Mylapore Kapaliswara Temple teaching there. Dancer and actress Kumari Kamala (later Kamala Lakshman), who had danced her way into the hearts of millions with her dance performances in films and was especially popular among middle class families, sought out traditional nattuvanars to teach her young daughters. By that time, Raja Rajeshwari Natya Mandir had started teaching Tanjore Bharatanatyam in Mumbai. Mrinalini Sarabhai, Shanta Rao and Ramgopal had gone to the village of Pandanallur in Tamil Nadu to learn dance from the doyen Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai. Each of them had begun to create their own styles of dance, and there was no need for an act to explicitly facilitate this. Historically, re-vivication and re-construction of the dance has happened continuously. We learn that 18th century dynastic musicians had already set in motion the reconstruction and formation of the adavus (basic units of Bharatanatyam) as listed in the Sangītasārāmrta. The famous Thanjavur Quartet redesigned and refined the adavusystem and composed a solo repertoire (Margam) with the foresight of performance at spaces outside the king’s court. “If at this time, an infrastructure for courtesan art to flourish had been negotiated, the courtesan’s art would have travelled entirely differently through the troubling times of disintegrating kingdoms, and the uprising anti-nautch movement of the late 19th century and early 20th century,” says Jeetendra Hirschfeld who has researched the dance form’s history. Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, who taught Rukmini Devi, was nervous about her first performance for the annual convention of the Theosophical Society in 1935, even though it was not an arrangetram, but a small showcasing of the usual dramas. He sent his son Chokkalingam Pillai to conduct the nattuvangam for this programme. “Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai was quite relieved with the response to the performance and he continued to teach me. Later, when he wanted to get back to his village, he sent Kattumannar Koil Muthukumara Pillai,” Rukmini Devi said. Appropriation of Devadasis’ dance to re-populating it with new “Brahmin” amateurs is another charge brought against Rukmini Devi. Professor S Swaminathan, who grew up in Pudukkottai, says that upper caste amateur musicians were always there. He can count 10 generations of serious amateur musicians in his family. Rukmini Devi invited the great veena player Karaikudi Sambasiva Iyer from this family to teach in Kalakshetra. Her own family had generations of musicians on her mother’s side, so it was not a surprise that middle class girls, boys and several non-Indians took to learning the art when it was available to them. Rukmini Devi Sanskritised and sanitised the dance is yet another allegation brought against her. However, the karana poses depicted in the 10th century temple of Brihadeeswara in Thanjavur, where the art was nurtured, are all from the Sanskrit treatise Natyashastra. Rukmini Devi said: “When I put questions about the meanings of gestures to my teacher Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, he was able to give me the meaning of the shlokas as he was a learned man.” Therefore, the gurus have traditionally always followed Sanskrit texts as the foundation of the

Remembering Neila Sathyalingam Festival 2021

By Soumee De “This is our second year of organising the Neela Sathyalingam festival. Her memory continues to inspire us, and we are motivated to strive to preserve our arts” said Aravinth Kumarsamy, Artistic and Managing Director. Remembering Neila Sathyalingam Festival 2021 was organized at the Stamford Arts Centre in presence of Singapore’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Dr Vivian Balakrishnan as the Guest of Honour. Apsaras Arts also launched AVAI, a digital platform, felicitated Smt Meera Balasubramanian as the second recipient of the Neila Sathyalingam Memorial Endowment Award and presented a thematic solo bharatnatyam performance “Nava Durga” by one of the senior students of Neila Maami, Dr Roshni Pillay Kesavan. On a beautiful Sunday evening on 7th February 2021, Apsaras Arts presented the Remembering Neila Sathyalingam Festival 2021, at the Stamford Arts Centre, Singapore. Singapore’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Dr Vivian Balakrishnan was the Guest of Honour at this second edition of the festival that was launched in February 2020. Since the launch of the festival, all live performances and tours were cancelled with the onset of the pandemic which encouraged Apsaras Arts team to re-invent itself and create a series of digital productions, curate digital works, host online events and webinars while reaching out to both Singapore and global audiences. To make the digital effiorts sustainable, Apsaras Arts launched our very own online platform AVAI @ Apsaras Arts that will continue to host and share our digital performances and events, in the new normal. AVAI is an exquisite word in the Tamil language which means “a place to congregate”, “ a town hall” etc. AVAI will host dance and music performances, lecture demonstrations, webinars and live stream events, available for the connoisseurs of the arts, students and researchers to watch 24 by 7. AVAI is part of our website www.apsarasarts.com, and can be accessed for free, pay per view, and subscribe for exclusive content. We had the honour of our guest of honour Minister Dr Vivian Balakrishnan launch AVAI @ Apsaras Arts by chiming a pair of “Salangai” (dance anklet bells) on this memorable day celebrating our founder Shrimathi Neila Sathyalingam’s birth anniversary. Visit AVAI: https://ksndevelops.com/apsaralive/avai/ The festival was celebrated by the presentation of a thematic solo Bharatanatyam performance NAVA DURGA by one of Smt Neila Sathyalingam’s senior student, Bharatha Kala Mani Dr Roshni Pillay Kesavan. Dr Roshni Pillay Kesavan opened the festival with an invocation to Lord Shiva “Nagendra Haraya” choreographed by Neewin Hershall. With balanced poise and minimalistic clean movements, she delivered the coamic energy exuded by the Lord of Dance. The evening’s performance was dedicated to Goddess Durga, the consort of Lord Shiva and her nine forms worshipped annually during the Navrathri festival. Choreographed by Dr Roshni Pillay Kesavan, each of the nine forms were re-told in dramatic splendor bringing out the best of traditional bharatnatyam story-telling techniques. Dr Pillay Kesavan’s depth of story-telling brought alive the varying characteristics and significance of the nine forms Shailaputri, Brahmachāriṇī, Chandrakaṇṭā, Kuṣhmāṇḍā, Skandamātā, Kātyāyanī, Kālarātrī, Mahāgaurī, Siddhidātrī. We thank her for generously sharing her art and debuting her new choreography at this festival. The festival also marked the presentation of the annual Neila Sathyalingam Memorial Endowment Award 2021 to the second recipient Smt Meera Balasubramanian, senior company dancer at Apsaras Arts and co-founder of Kaplavriksha Fine Arts in recognition of her achievements in Indian Classical Dance in Singapore. This includes a citation and a cash award to encourage Singapore based dancers to pursue their passion. “Neila mami was a pioneer in promoting Indian arts and culture in Singapore and I’m elated to receive this award that’s named after her. I thank Apsaras arts for recognizing my contribution. Special mention to Aravinth Kumarasamy for constantly guiding me through this artistic journey and making me part of so many iconic productions of Apsaras arts”, said, Meera Balasubramanian in her acceptance speech. In summary, Aravinth Kumarsamy, Artistic and Managing Director said, “This is our second year of organising the Neela Sathyalingam festival. Her memory continues to inspire us, and we are motivated to strive to preserve our arts.”

Rhythm in Joy

By Leela Samson About the book: Rhythm in Joy is an authoritative introduction to five of India’s Classical dance forms. The intention of this work is to view the distinctive features of these forms through the eyes of a dancer- the historical and cultural context in which they evolved and the particularities of technique and presentation that characterize each form. The first chapter deals with the corpus of myth and legend from which our art forms in general draw their substance, and the following with the texts that determine the parameters of classical dance. Each of the five styles chosen are then described separately in terms of their particular history, ambience, mode of expression and style of presentation. It is true that varying schools exist within each dance form in India, and that each of these is represented by a host of teachers and performers. A complete appreciation of the development of a dance form would include all these viewpoints. But the present work does not pretend to be definitive. It seeks, rather, to promote an understanding of each style by elucidating a particular point of view. Thus the book has followed the method of illustrating each dance style with the work of a particular exponent-cum-teacher. In commenting upon the classical styles of dance in India, it is usual for scholars to draw comparisons between them. This exercise is unacceptable to the author, who accords to each style its own validity, notwithstanding India’s common heritage of myth and tradition. Such comparisons, she feels, would not do justice to the unique aesthetic appeal of individual styles. In keeping with this pluralistic approach, the visual component of the book, too, stresses the element in each style which highlights its distinctness from others: the elaborate process of make-up and costuming in Kathakali, for instance, the vigour of the male dancers in Manipuri, the dignity of stance in Kathak, the strong lines of Bharatanatyam, the hastas and foot-positions peculiar to Odissi. While thus paying homage to the richness and variety of Indian dance forms, the book avoids the extremes of abstruseness and over-simplification which have frequently marred works on the subject. Rhythm in Joy is the ideal guide for anyone who has been dazzled and intrigued by the complexity of Indian dance and felt the need for a deeper understanding of it. About the Author Leela Samson is an alumna of Kalakshetra, one of India’s foremost art institutes. Her skills and her philosophy were moulded by the institute and its founder, Rukmini Devi. Today, Leela is one of India’s best-known exponents of Bharata Natyam. She teaches in Delhi at the Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra. She has been writing occasional articles on dance for magazines and her recent articles include the Festival of India booklet, Dance in India, and a contribution to APA International Guides on the dance and music of India. This is Leela Samson’s first book, and she hopes to write another on dance for children.